NASA's Curiosity Rover Poised to Drill Into Mars

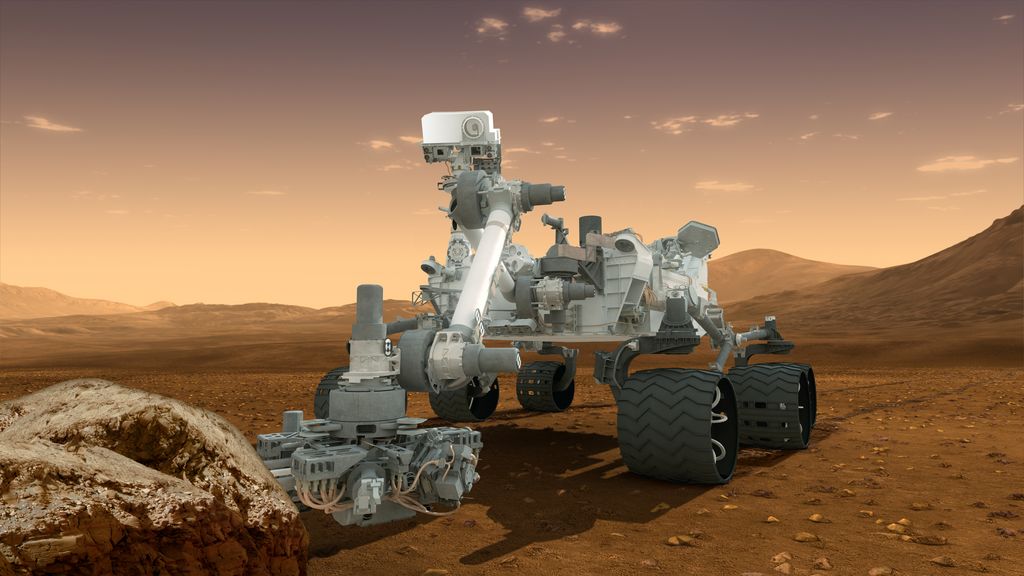

NASA's Mars rover Curiosity is sizing up a target rock and flexing its robotic arm ahead of its first-ever drilling activity on the Red Planet, which should take place in the coming days.

The 1-ton Curiosity rover pressed down on the rock in four different places with its arm-mounted drill Monday (Jan. 27). These "pre-load" tests should allow mission engineers to see if the amount of force applied matches predictions, researchers said.

The six-wheeled robot won't be ready to start boring into the rock until it completes several additional hardware tests and other checks, which should keep the rover busy through at least the end of this week, they added.

Curiosity's next step is an overnight pre-load test, which will tell the rover team if the big temperature swings at Curiosity's Gale Crater landing site pose any potential problems for drilling operations.

Air temperatures at Gale can drop from 32 degrees Fahrenheit (0 degrees Celsius) in the afternoon to minus 85 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 65 degrees Celsius) at night. The rover's chassis, arm and mobility system can grow and shrink by about 0.1 inches (0.25 centimeters) over such a broad temperature range, researchers said.

"We don't plan on leaving the drill in a rock overnight once we start drilling, but in case that happens, it is important to know what to expect in terms of stress on the hardware," Limonadi said.

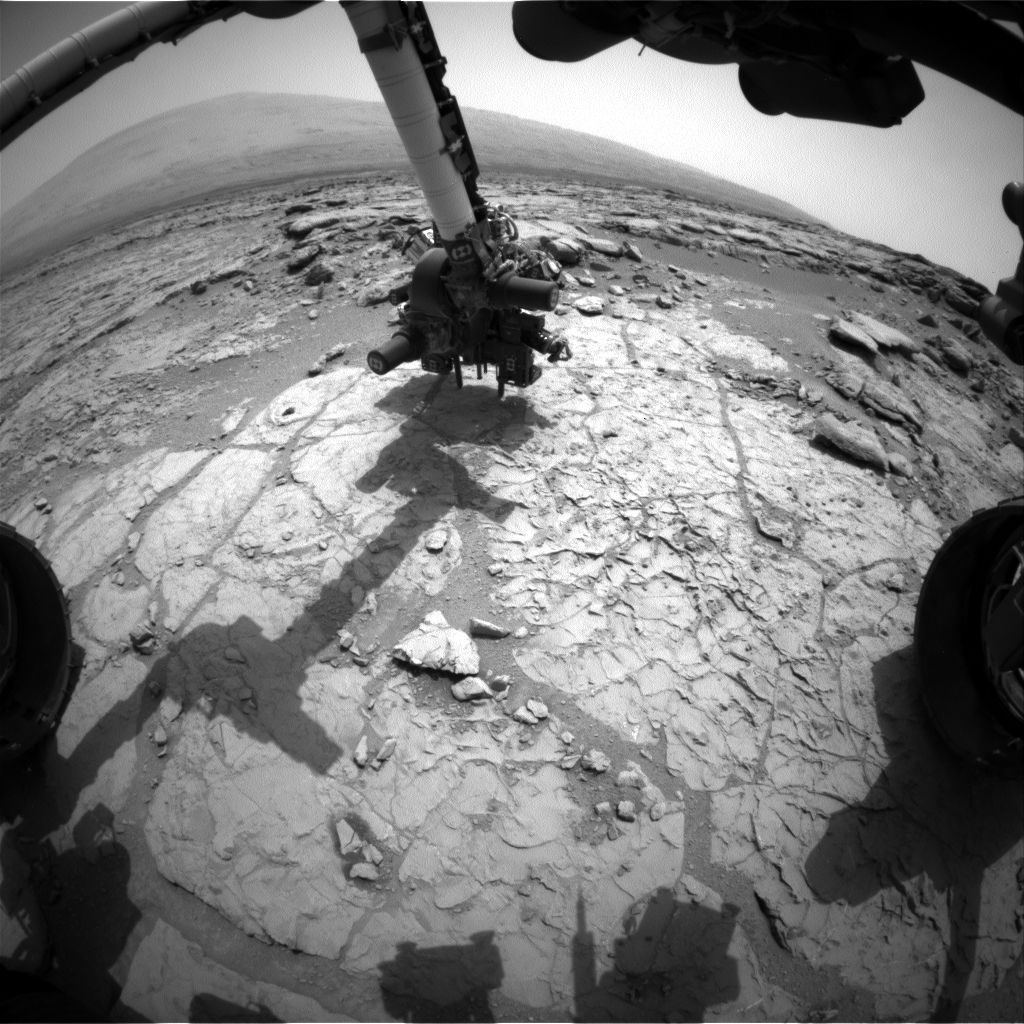

Other pre-drilling activities include a detailed assessment of the target rock, which is part of an outcrop that mission scientists have dubbed "John Klein." The team will also employ the drill's hammering action briefly without actually spinning the drill bit, to make sure the percussion mechanism and associated systems are working properly.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

And the first bite Curiosity actually takes out of a rock will not produce samples for analysis, researchers said. Rather, the rover will perform a "mini-drill" activity, going less than 0.8 inches (2 cm) into the rock — too shallow to push powder into the drill's sample-snagging chamber.

"The purpose is to see whether the tailings are behaving the way we expect," Limonadi said. "Do they look like dry powder? That's what we want to confirm."

Curiosity landed on Aug. 5 of last year, kicking off a surface mission to determine if the Gale Crater area has ever been capable of supporting microbial life. The robot carries 10 different science instruments to aid in this quest, along with other tools such as the drill, which can bore 1 inch (2.5 cm) into solid rock.

The Curiosity team wanted to test the drill out on a suitably intriguing target, and "John Klein" seems to qualify. The outcrop is shot through with light-colored mineral veins that were likely deposited by flowing water long ago.

Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.