How New Mars Rover Will 'Cook' Red Planet Rocks

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The recipe for seeking habitability on the Red Planet using NASA's next rover will start with a pinch of Mars — either a few grains of soil or a wisp of atmosphere.

Scientists will then follow a simple recipe: Place the Martian bit into the rover's Sample Analysis of Mars (SAM) instrument, cook to up to 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit (980 degrees Celsius), then measure the result.

The new rover, Curiosity, is the centerpiece of the Mars Science Laboratory Mission, which launched in November 2011 and is due to land on Mars Aug. 6. The $2.5 billion project is aiming to learn whether Mars is, or ever was, hospitable to life.

Article continues belowNASA tried an experiment similar to SAM almost 40 years ago on its Viking Mars landers, and the results are still being debated today. For example, the landers' discovery of chlorine compounds in the soil was initially believed to be cleaning fluid contamination, but a 2011 study hypothesized these could have been leftovers of organic life.

SAM, says NASA, will produce far more precise results.

"The surface experiments on Viking were designed to do a home-run-swing-for-the-fences life detection experiment," said Ashwin Vasavada, MSL's deputy project scientist. "SAM is significantly more capable than Viking ... it can find much larger molecules and it can detect things more sensitively." [11 Amazing Things NASA's Huge Mars Rover Can Do]

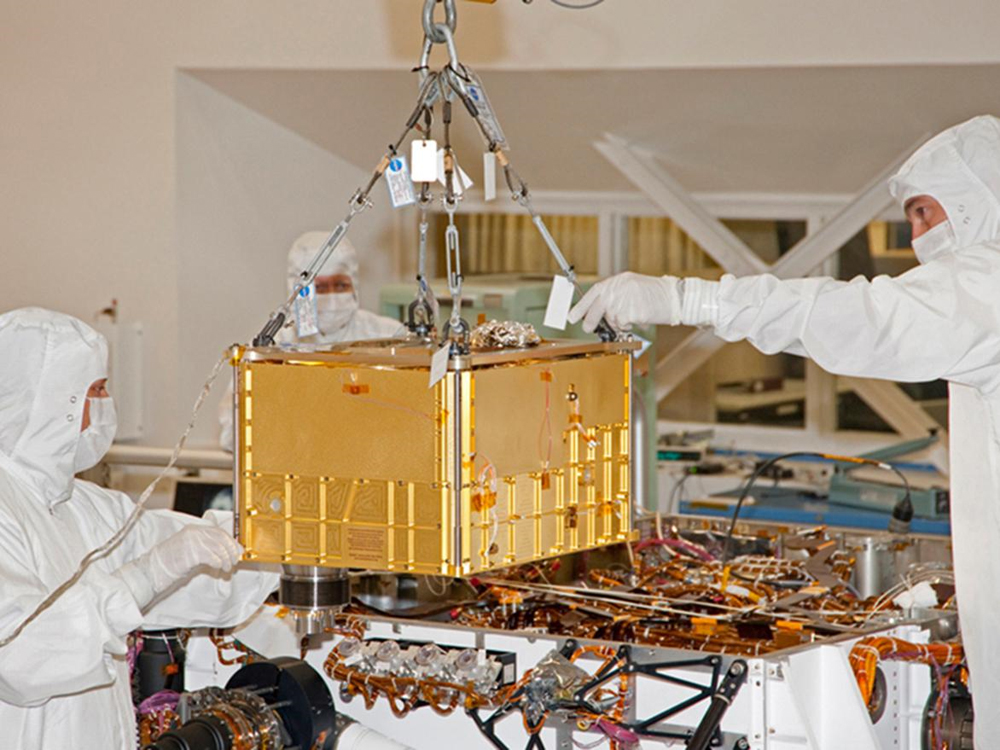

The microwave-size experiment package, wedged in the front of the Mini Cooper-size rover, is so complex that NASA considers SAM itself more complicated than many of its spacecraft.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Samples inside the package must first be "cooked" in an oven, then analyzed using instruments commonly found on the shelf of respectable scientific laboratories on Earth.

"Different constituents in that sample will break down at different temperatures and become gas," said Vasavada.

Clay, Vasavada said as an example, begins to break down at 530 degrees Fahrenheit (277 degrees Celsius). Therefore, a puff of water appearing on a Martian sample cooked to that temperature would imply that it is partly made of clay.

SAM includes a gas chromatograph made up of six different tubes; each one is able to pick up a different kind of compound.

"You flow gas from the samples through fairly long tubes that are specifically designed to separate out the different constituents of the gas," Vasavada said. "You put in a mixture of gases at the beginning of the tube, and by the end of the tube, they're separated out."

SAM also has two kinds of spectrometers for a more precise identification of each sample. The spectrometers can catalog potential life signature gases such as carbon dioxide, methane and water vapor. The spectrometers will also measure properties including molecular weight, electrical charges and the amount of light absorbed at different wavelengths.

If SAM does spy a potential organic, it will aim to determine if it's actually from Mars, or hitchhiking strays from Earth contaminating the sample collector.

Stashed on the front of Curiosity, underneath foil covers, are five ceramic blocks spiked with artificial organic compounds. The rover will drill into the block and cook a sample from it. If organics pop up that weren't supposed to be in the block, researchers will more likely rule that the organics found on Mars were stowaways.

By contrast, if the sample comes back pure, researchers can then focus on identifying clues as to where the organics came from. It will be hard for NASA to definitively say if an organic is of biological origin or not, but they say the research they do with MSL will help guide future missions.

Considered the workhorse of MSL, SAM is one of the main reasons the mission came about in the first place, mission planners say.

"We don't like to have favorite instruments," Vasavada said, "but if you trace back why we were flying this rover, it was to fly a mass spectrometer to Mars."

Editor's Note: This article was corrected to change the word "smaller" to "larger" in Vasavada's quote, "SAM is significantly more capable than Viking ... it can find much larger molecules and it can detect things more sensitively."

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.