Excitement Builds Over Expected Higgs Boson Announcement

This story was updated at 12:38 p.m. EDT.

Anticipation is rising over the expected announcement soon of more evidence for the existence of the long-sought Higgs boson particle.

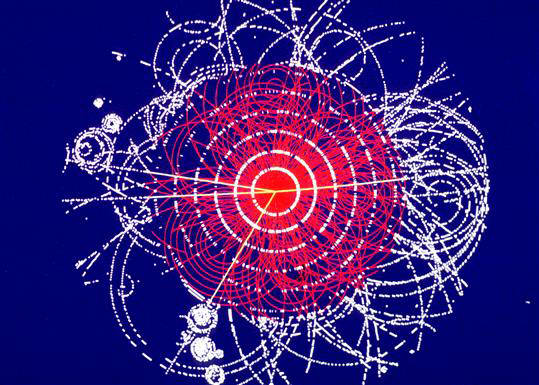

The Higgs has been theorized for years, but never found. Humanity's best hope of discovering the particle lies in the humongous atom smasher buried underneath Switzerland and France called the Large Hadron Collider (LHC). There, physicists collide protons head-on to create explosions that give rise to new, exotic particles, including, maybe, the Higgs.

LHC researchers plan to share their latest findings at the International Conference on High Energy Physics (ICHEP) in Melbourne, Australia, from July 4-11.

In December of last year, LHC scientists at the machine's home facility, the CERN physics laboratory in Geneva, reported they'd seen hints of what could be the Higgs boson in an excess of particles weighing about 124 or 125 gigaelectronvolts, or GeV, a unit roughly equivalent to the mass of a proton. However, the physicists hadn't accumulated enough data to announce a discovery, which in science requires a certain level of statistical significance called "five sigma."

Experts say it's still unlikely the LHC researchers have reached the five-sigma level yet, but they have collected substantially more data since their last public announcement. [Top 5 Implications of Finding the Higgs Boson]

"They will have quite a bit more data now, but the analysis is still ongoing," said CERN press officer Renilde Vanden Broeck. "So we will have to wait and see."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The findings reported so far have been called "tantalizing hints" of the Higgs' existence by LHC physicists, but it remains possible that the signal researchers see is merely a statistical fluke.

"This is science," Vanden Broeck told LiveScience. "They are not going to announce a discovery until they are absolutely sure, when it's a real five-sigma."

And if the signal does come through more strongly in the new data, it will still take some investigation to determine if it represents the Higgs boson or something else even more exotic.

"It's a bit like spotting a familiar face from afar," CERN director general Rolf Heuer said in a statement. "Sometimes you need closer inspection to find out whether it's really your best friend, or actually your best friend's twin."

The Higgs has been garnering a lot of attention for a subatomic particle that has little impact on most people's everyday lives. Yet in physics, it is thought to hold the key to explaining why matter has mass. Scientists theorize a Higgs field pervading space bestows mass on particles as they pass through it. Depending on the strength of their interactions with this field, they will be more or less massive.

Though the field is thought to be undetectable, it would have an associated particle, the Higgs boson, that could give it away. The particle has been called the "God particle" because of its importance, though many physicists shun the moniker, which the public and press have embraced.

CERN physicists say they welcome the widespread excitement over the Higgs, while cautioning people to be patient until a true discovery can be made.

"We have calls all the time," Vanden Broeck said, adding that Higgs' rumors have been trending on Twitter recently. "It's always great there's public interest."

Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.