Sunday's Solar Eclipse 'Ring of Fire': Where and How to See It

UPDATE: For the latest tips and advice on seeing the May 20 solar eclipse, see: Annular Solar Eclipse of May 20: Complete Coverage

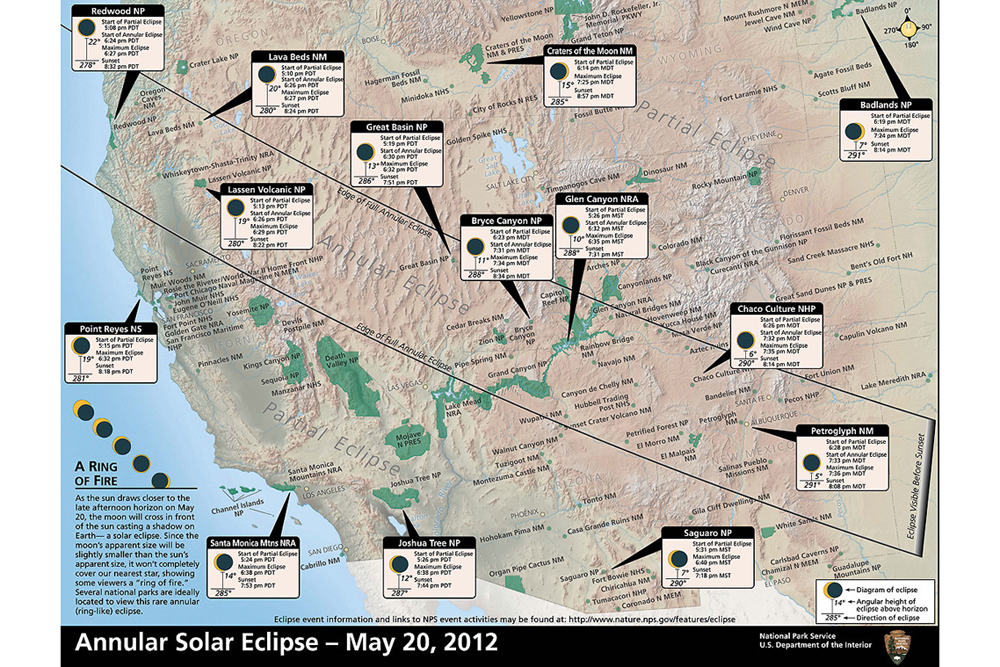

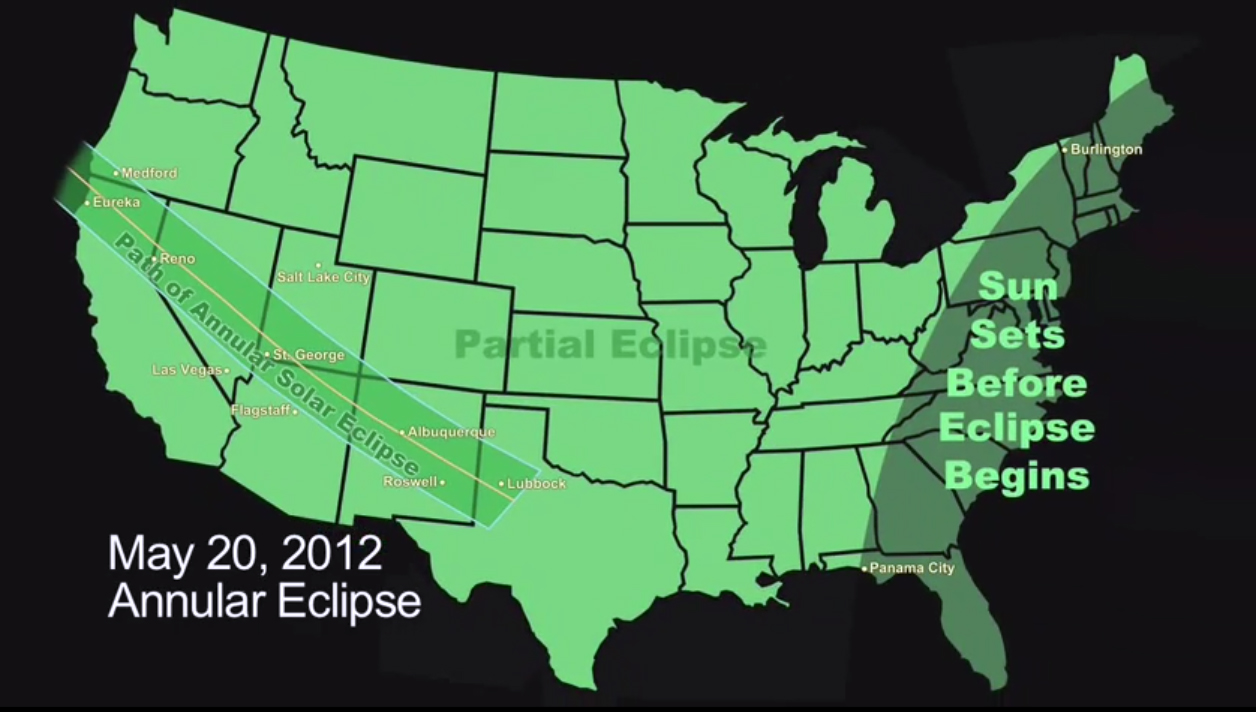

On Sunday afternoon (May 20), the path of an annular solar eclipse will cross parts of eight western states. SPACE.com estimates that an estimated 6.6 million Americans live within the path of annularity.

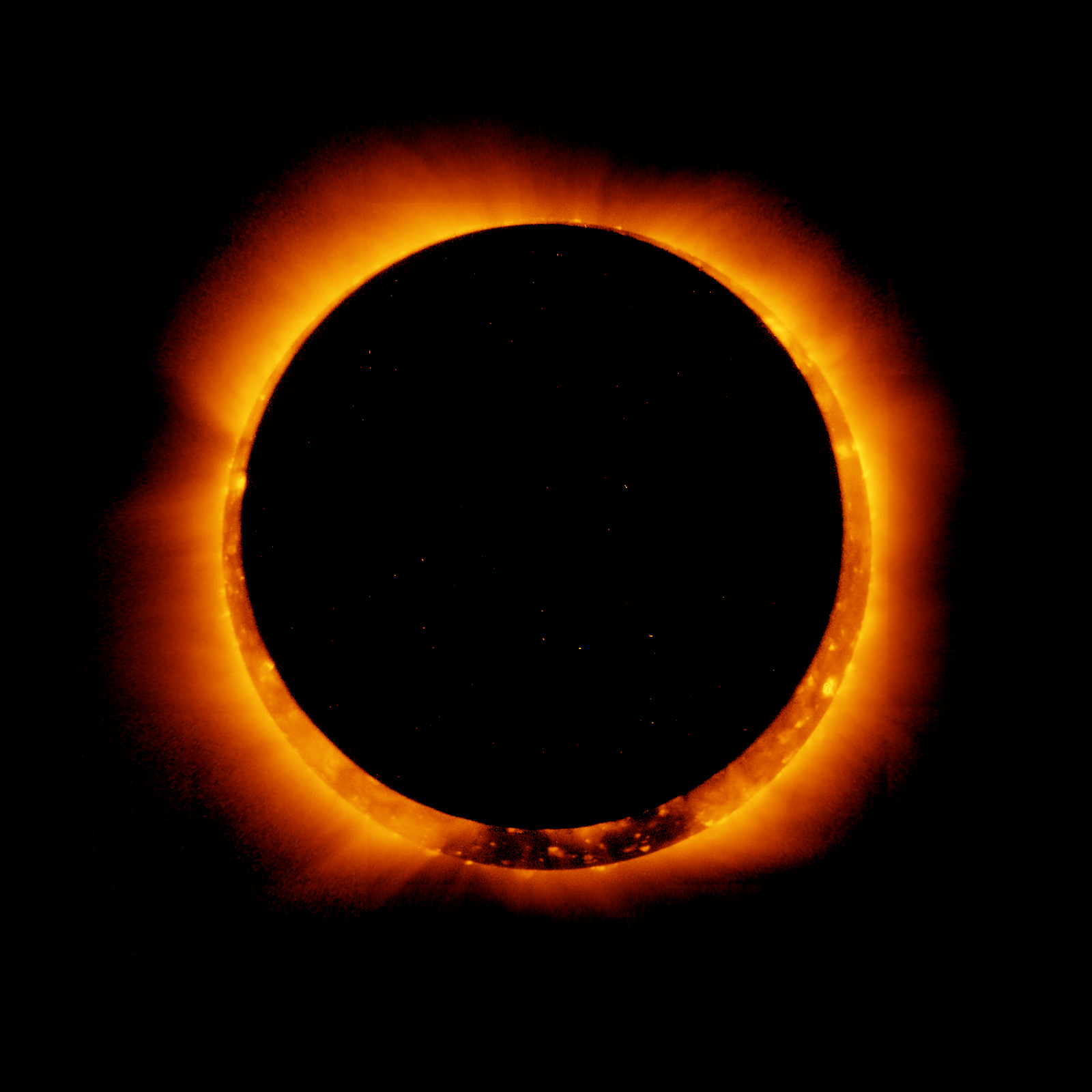

An annular solar eclipse is typically no match for a total solar eclipse. It is really more like an embellished partial eclipse, with the beautiful solar corona not becoming visible and the sky never getting really dark. Nevertheless, an annular solar eclipse still ranks as one of the most remarkable of celestial sights for avid skywatchers.

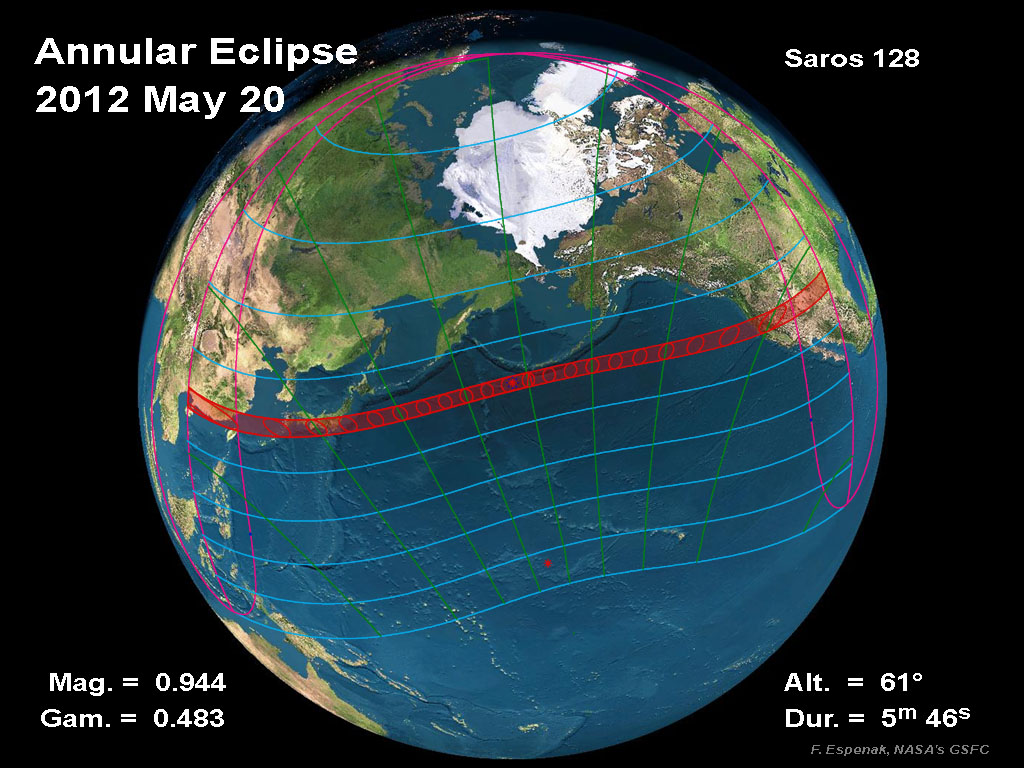

Sunday's eclipse track begins in East Asia and crossed the Pacific Ocean before reaching North America. In the United States, the U.S. National Park Service has invited skywatchers to view the solar eclipse from a national park, while the University of Colorado, at Boulder is opening its Folsom Stadium — a football stadium — to the public in what organizers are calling the world's largest solar eclipse viewing party.

If you're planning to position yourself within the path of Sunday's annular solar eclipse you’re going to have one of three observing options to choose from:

1) Position yourself at or near the center of the eclipse track.

2) Position yourself just inside the northern or southern limit of the eclipse track.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

3) Position yourself near the sunset point of the eclipse track.

Let’s look closely at each option, starting with being located at or near the center of the eclipse track, which is likely where the lion’s share of eclipse chasers plan to go. [Solar Eclipse of May 20 (Photo Observing Guide)]

In the middle

From here what you will see is a gradually increasing partial solar eclipse until the moon is almost at the middle of the sun; the annular eclipse begins when the moon detaches itself from one inner side of the sun.

You'll then see the sun morph into a lopsided "ring of fire" — one side shining brighter than the other — that, at mid-eclipse will appear as a perfect ring; the moon’s dark disk will measure 94.4 percent of the apparent diameter of the bright sun behind it. Then, as moon continues to move on its way, the ring will become off-centered again. The end comes when the dark silhouette of the moon touches the other side of the sun.

The main attraction for being on the center line is that the duration of annularity lasts the longest. At the Pacific Coast in northern California, not far from the town of Requa, the ring phase will last for 4 minutes, 47 seconds with the sun standing 22 degrees high in the west-northwest sky (your clenched fist held at arm’s length is roughly equivalent to 10 degrees).

Heading southeast along the center of the track, the duration of annularity slowly diminishes, while the sun’s altitude gradually lowers. From Albuquerque, the ring will persist for 4 minutes 27 seconds, but the sun will have lowered to just 5.5 degrees above the horizon. If we were to divide the total duration of annularity into thirds (beginning, middle and end), then the appearance of a near-perfectly centered ring should last about 90 seconds.

Being on edge

Now let's consider the aspects of being positioned just inside either the northern or southern limit of the eclipse track. At first this doesn't seem like much of an option, since the duration of annularity will be much less and the ring will always appear off-center.

Indeed, just 1 mile inside the track, annularity will last only about 35 seconds, while going 3 miles in will give you about a minute's worth of annular eclipse. But the moon's limb, unlike the sun, is not smooth. Lunar mountains and valleys roughen its profile and when these touch the inside of the sun's edge at the beginning and end of annular eclipse, they can break the thin line of light into a string of points called Baily's Beads. [Sun Quiz: How Well Do You Know Our Star?]

This phenomenon might not last more than a few brief seconds on the center line, but for those stationed at the edges of the path they could last through the duration of annularity.

Paul D. Maley who worked at the NASA Johnson Space Center from 1969 to 2010 and who has led many eclipse expeditions (http://www.eclipsetours.com/about-us/) says:

"I can attest from personal decades of past experience with annulars that observing a solar eclipse at the edge (also called the 'graze zone') is much more unique than that at the center, especially if you have already seen an annular eclipse from the centerline. At the north graze zone, large beads are seen (just the opposite from a total solar eclipse) and from the south graze zone, tinier beads will be detected. From the graze zones, the sun penetrates valleys of different depths and expose what can be a startling array of dazzling points of light."

Observing from near the edge of the eclipse track is also scientifically important in that it can serve to measure small variations in the diameter of the sun. Interestingly, there are two similarly sized cities that are situated exactly on the edge of annularity. On the north edge of the path is Cortez, Colo. (pop. 8,482), while on the south edge is Winslow, Ariz. (pop. 9,832).

A ringed sunset

The most intriguing possibility is to see the sun mimic a ring of fire as it is about to set, which makes an already striking sky event all the more dramatic. There's the possibility of vivid sunset colors, other interesting atmospheric phenomena, and beautiful foreground scenery. Of course, in the case of a setting sun any calculation assumes you have a clear, flat horizon. Any foreground obstructions in the west-northwest (at about azimuth 295 degrees) will put a premature end to the sun's visibility.

Lubbock, Texas, is not on center line, but is about 25 miles to the northeast. From there, an almost perfect ring will be formed, lasting 4 minutes 14 seconds beginning at 8:33:54 p.m. CDT. But the sun will be only 1.3 degrees above the horizon when the annular eclipse begins.

Annularity will end six minutes before sunset. Farther to the southeast, the effect of atmospheric refraction must be taken into account. The thick atmosphere at the horizon refracts or bends sunlight so that we are seeing the setting sun about a half degree above where it really is.

In Snyder, Texas, for example, calculations neglecting refraction suggest that only the beginning of the 3 minute 40 second ring phase (at 8:33:43 p.m. CDT) will be visible before the sun drops below the horizon, but taking refraction into account shows that the sun will remain above the horizon for another nine minutes. At Sweetwater, Texas, the sun will resemble a horseshoe with narrow, pointed tips tilted down and to the right when it transitions to a lopsided ring at 8:34:27 p.m. CDT. Less than three minutes later, the sun will set.

And you will also have to hope that the weather cooperates, for even if the sky is mainly clear there is always the possibility that clouds could lie close to the horizon, which could, of course, spoil the view at the critical moment.

Eye safety concerns

Lastly, we need to address the issue about watching the eclipsed sun as it sets, for in this special case it could be dimmed and reddened to an unpredictable degree, which can present a number of uncertainties. [How to Safely Observe the Sun (Infographic)]

Of course, when the sun is high and blindingly bright you're going to need to use a safe sun-viewing filter such as a No. 14 rectangular arc welder’s filter; the standard for a normal daytime sun, or a metalized Mylar filter manufactured specifically for solar viewing. Don't rely on other filter materials such as smoked glass, sunglasses or crossed polarizing filters; they may pass dangerous amounts of invisible infrared light that can burn your retina.

On a telescope, binoculars, or camera, the filter must be attached securely over the front of the instrument, never behind the eyepiece.

A dim, red setting sun, however, is another question altogether.

Many people have watched sunsets all their lives without any second thoughts. But caution is still advisable. While it is true that the sun’s ultraviolet radiation — the most damaging to the eye — is extinguished when sun turns a deep red, by the same token, infrared radiation can be expected to cut through the thick air much more strongly than visible light does. And retinal damage can happen painlessly — just because everything feels OK doesn’t mean it is.

So even if the sun is quite dim, it’s still a good idea to limit yourself to brief looks. All you lifelong sunset-watchers might be surprised to hear such a warning, but it’s better to be safe than sorry.

Good look and clear skies to all on Sunday!

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.