Is the New Physics Here? Atom Smashers Get an Antimatter Surprise

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

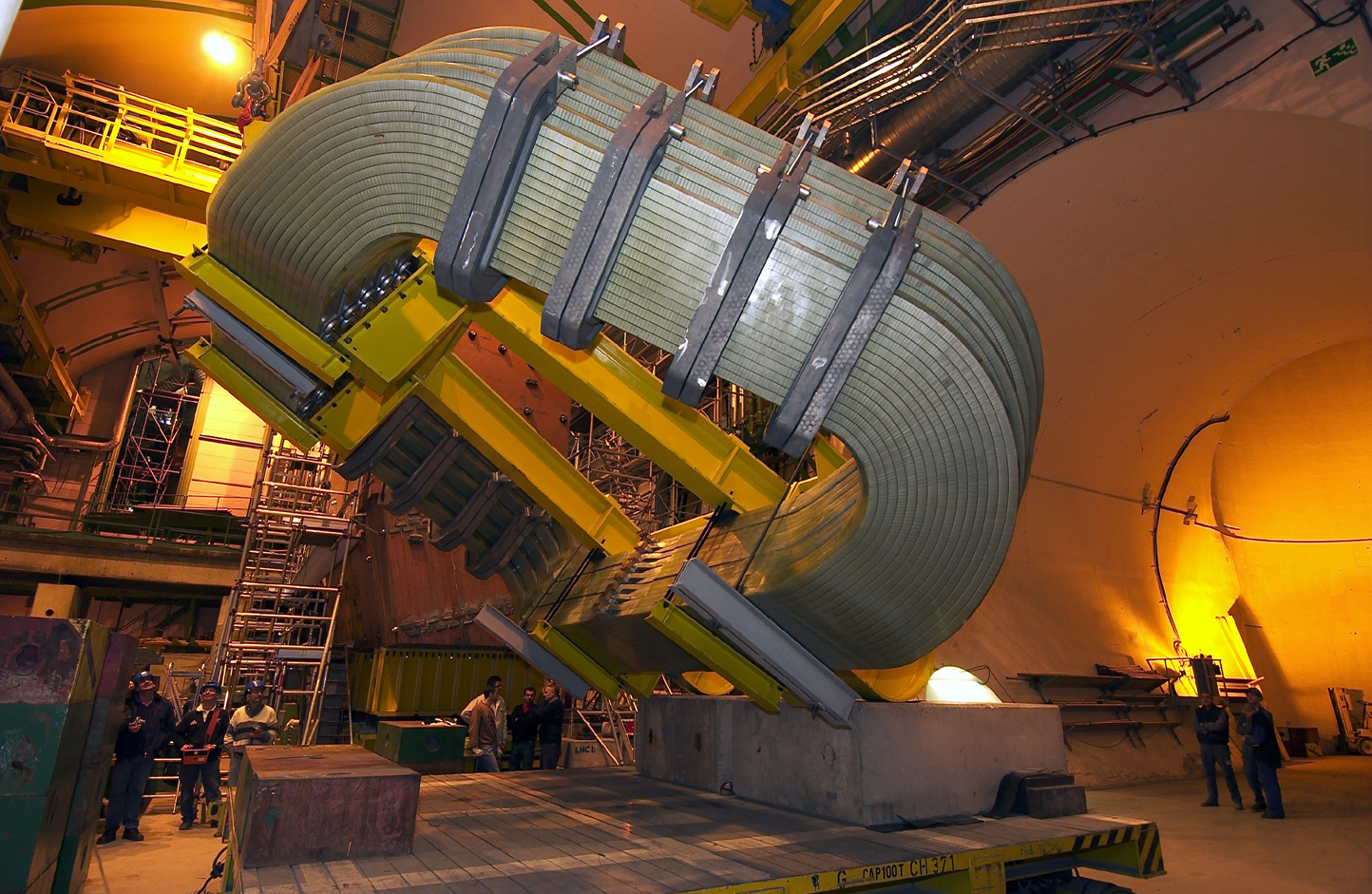

The world's largest atom smasher, designed as a portal to a new view of physics, has produced its first peek at the unexpected: bits of matter that don't mirror the behavior of their antimatter counterparts.

The discovery, if confirmed, could rewrite the known laws of particle physics and help explain why our universe is made mostly of matter and not antimatter.

Scientists at the Large Hadron Collider, the 17-mile (27 km) circular particle accelerator underground near Geneva, Switzerland, have been colliding protons at high speeds to create explosions of energy. From this energy many subatomic particles are produced.

Now researchers at the accelerator's LHCb experiment are reporting that some matter particles produced inside the machine appear to be behaving differently from their antimatter counterparts, which might provide a partial explanation to the mystery of antimatter. [The Coolest Little Particles in Nature]

Missing antimatter

Scientists think the universe started off with roughly equal amounts of matter and antimatter. (Particles of antimatter have the same mass of their twins but an opposite charge.) Somehow over the ensuing 14 billion years, most of the antimatter was destroyed, leaving a leftover universe of mainly matter.

One potential explanation for this outcome is called "charge-parity violation." CP violation means that particles of opposite charge behave differently from one another.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The LHCb researchers found preliminary evidence that this is happening when particles called D-mesons, which contain "charmed quarks," decay into other particles. The whimsically named charmed quarks, like many exotic particles, are so unstable, they last only a fraction of a second. They quickly decay into other particles, and it is these products that the experiment detects. ("LHCb" is short for LHC-beauty, another flavor of quark.)

From the experiment, the researchers found a 0.8 percent difference in the probabilities that the matter and antimatter versions of these particles would decay into a particular end state.

Ruling out a fluke

When it comes to particle physics, it's all about the quality of statistics. Measuring something once is meaningless because of the high degree of uncertainty involved in such exotic, small systems. Scientists rely on taking measurements over and over again — enough times to dismiss the chance of a fluke.

The new finding ranks as a "3.5 sigma" result, meaning the statistics are solid enough that there is only a 0.05 percent likelihood that the pattern they see isn't really there. For something to count as a true discovery in particle physics, it must reach a 5 sigma level of confidence.

"It's certainly exciting, and certainly worth pursuing," LHCb researcher Matthew Charles of England's Oxford University told LiveScience. "At this point it's a tantalizing hint. It's evidence of something interesting going on, but we're keeping the champagne on ice, let's say."

By the end of 2012, Charles said, the Large Hadron Collider should have collected enough data to either confirm or reject the result.

LHC's birthright

If the finding is borne out, it would be a big deal, because it would mean the reigning theory of particle physics, called the Standard Model, is incomplete. Currently the Standard Model does allow for some minor CP violation, but not at the level of 0.8 percent. To explain these results, scientists would have to alter their theory or add some new physics to the existing picture.

In either case, the LHC would have begun to claim its birthright.

"The whole driving purpose of the LHC is to discover and understand new physics beyond the Standard Model," Charles said. "This sort of analysis is exactly why I joined LHCb."

One possible example of the kind of new physics that might explain such CP violation is called supersymmetry. This theory suggests that in addition to all the known particles, there are supersymmetric partner particles that differ by half a unit of spin. Spin is one of the fundamental characteristics of elementary particles.

So far, no one has found direct evidence of supersymmetry. But if supersymmetric particles exist, they might be created instantaneously and disappear again during the particle-decay process. That way they could interfere with the decay process, potentially explaining why matter and antimatter decay differently.

Charles reported the LHCb team's findings this week in Paris at the Hadron Collider Physics Symposium.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. For more science news, follow LiveScience on twitter @livescience.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.