Final Grave of Fallen NASA Satellite May Stay a Mystery

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

A dead NASA climate satellite definitely fell back to Earth early this morning (Sept. 24) — but we may never know exactly where, agency officials said today.

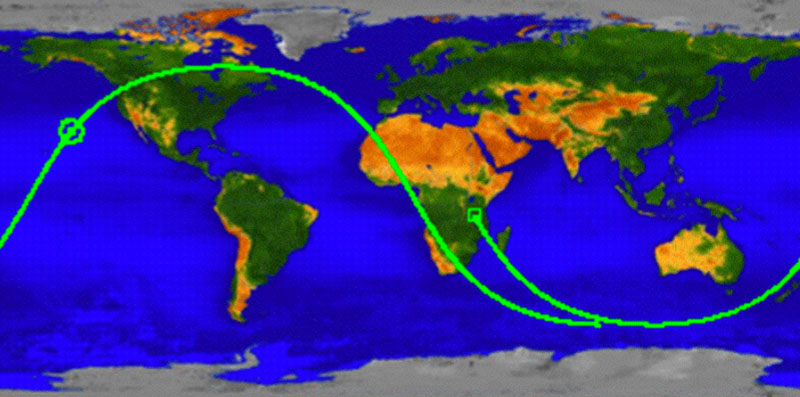

The Upper Atmospheric Research Satellite (UARS) re-entered Earth's atmosphere overnight, most likely within 20 minutes of 12:16 a.m. EDT today (0416 GMT), Nick Johnson, chief orbital debris scientist at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston, told reporters during a news briefing today. At that time, it would have fallen into the Pacific Ocean, well off the coast of North America, he added.

However, determining exactly when the satellite's plunge occurred, and where, is not an easy thing.

"We may never know," Johnson said.

That's because NASA and the U.S. Joint Space Operations Center at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California rely on ground-based radars and optical sensors at 25 sites worldwide to gather data about where dead satellites, like UARS, are located. These sensors make up the Space Surveillance Network. Sometimes, though, the spacecraft may not be passing over any of them. [Photos of NASA's Huge Falling Satellite UARS]

"One of the ways you find out a satellite is no longer in orbit is you have sensors in the Space Surveillance Network go look for it, and if they don’t find it then it has re-entered," Johnson explained.

To make sure a spacecraft has truly fallen back to Earth, it must have missed three opportunities to have been spotted by sensors. "In this particular case it took a while for the satellite track to go over three sensors," Johnson said. "Sometimes it happens, it's not uncommon at all."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

For that reason, it took NASA several hours to confirm that UARS had re-entered, and the agency still isn't able to pinpoint exactly when. If the spacecraft fell even about five minutes after 12:16 a.m. EDT (0416 GMT), then it might have fallen over Canada. However, so far NASA has received no credible reports of people on the ground observing the spacecraft's plunge, Johnson said.

"UARS, whether it came in during the local day or local night, would have clearly been visible," Johnson said. "If we continue to have a lack of reports of seeing something that looks like a re-entering UARS, that would give further credence to the fact that it was probably over water."

There are, however, an abundance of incredible reports. Many people around the world have already exchanged photos and videos of what they think might have been the death plunge of UARS. Almost all of these people, however, were in parts of the world significantly removed from where the satellite was passing over at the time.

The $750 million satellite was launched in 1991 to study Earth's ozone layer, and was decommissioned in 2005. At 6.5 tons, UARS was the largest NASA satellite to fall uncontrolledfrom space since 1979. [6 Biggest Spacecraft to Fall Uncontrolled From Space]

NASA and the Joint Space Operations Center will continue to investigate the fall of UARS. But ultimately, officials said they anticipate being left with some mysteries.

"This is not an unusual event," Johnson said. "We do not always know precisely where these re-entries occur and this is not a unique situation to UARS."

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.