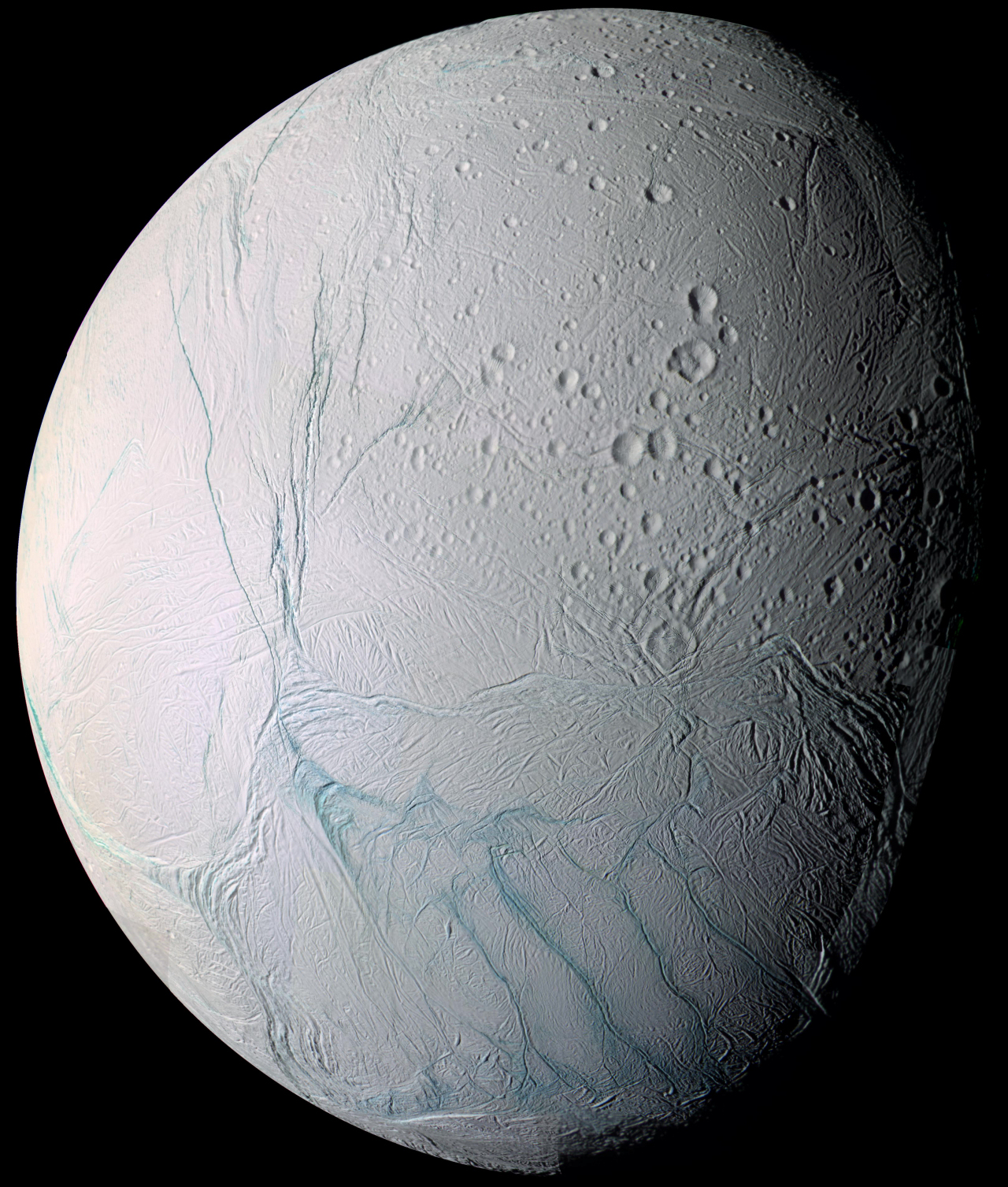

Saturn Moon Enceladus' Buried Ocean Comes Close to Surface

The ocean beneath the icy shell of Saturn's moon Enceladus rises nearly to the surface in some places, a new study suggests.

Measurements by NASA's Cassini spacecraft indicate that as little as 1.2 miles (2 kilometers) of ice may cover the ocean in the moon's south polar region, according to the study.

"This discovery opens new perspectives to investigate the emergence of habitable conditions on the icy moons of the gas giant planets," Nicolas Altobelli, the European Space Agency's (ESA) project scientist for the Cassini-Huygens mission, said in a statement. [Photos of Enceladus, Saturn's Geyser Moon]

"If Enceladus' underground sea is really as close to the surface as this study indicates, then a future mission to this moon carrying an ice-penetrating radar sounding instrument might be able to detect it," added Altobelli, who was not involved in the new study.

In 2005, Cassini discovered jets of water ice, organic molecules and other material blasting into space from four large "tiger stripe" fissures near Enceladus' south pole. Scientists think this stuff is coming from the underground ocean, which is believed to be in contact with Enceladus' rocky mantle.

Such discoveries have led most astrobiologists to regard Enceladus as one of the solar system's best bets to host alien life, along with the Jupiter moon Europa (which also harbors an ocean beneath its ice shell).

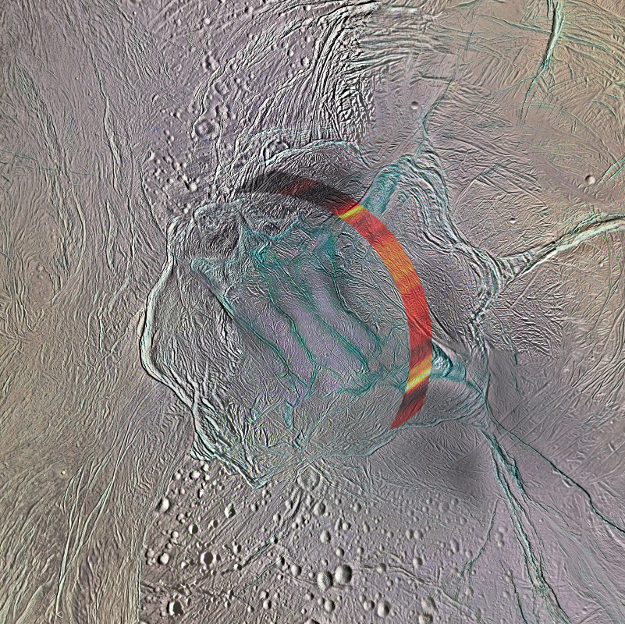

For the new study, the researchers analyzed observations that Cassini made of a 310-mile-long (500 km) swathe of ground just north of the tiger stripes. The probe made these observations using its radar instrument during a November 2011 flyby of Enceladus. (The mechanics of the flyby prevented measurement of the tiger-stripe area itself, ESA officials said.)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The radar data suggest that temperatures a few meters below the surface in this area are between minus 350 degrees Fahrenheit and minus 370 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 213 to minus 223 degrees Celsius). That's extremely cold, obviously, but it's up to 36 degrees Fahrenheit (20 degrees C) warmer than scientists had thought, team members said.

This "thermal anomaly" in turn suggests that Enceladus' ice shell is quite thin at and around the south pole, perhaps just 1.2 miles (2 km) thick in places, the researchers said.

The new results are broadly consistent with the findings of a 2016 study by a different research team, which was based on Cassini measurements of Enceladus' gravity and shape, as well as the way the moon wobbles. The 2016 study determined that the ocean is 11 miles to 14 miles (18 to 22 km) thick on average but thins to less than 3 miles (5 km) near Enceladus' south pole.

The new study was published Monday (March 13) in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.