Physicists Debate Discovery of Gravitational Ripples from the Big Bang

NEW YORK – The physics world was agog in March over the announcement that astronomers had possibly found ripples in space-time from the earliest moments of the universe. But some scientists now question whether the findings may be nothing more than galactic dust.

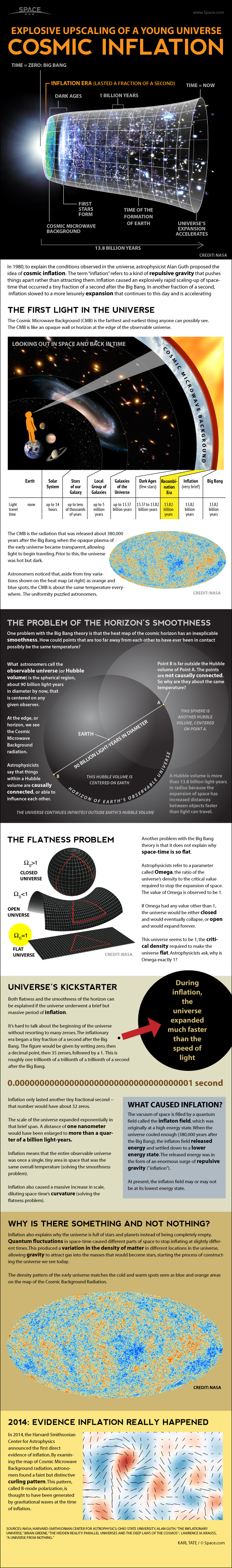

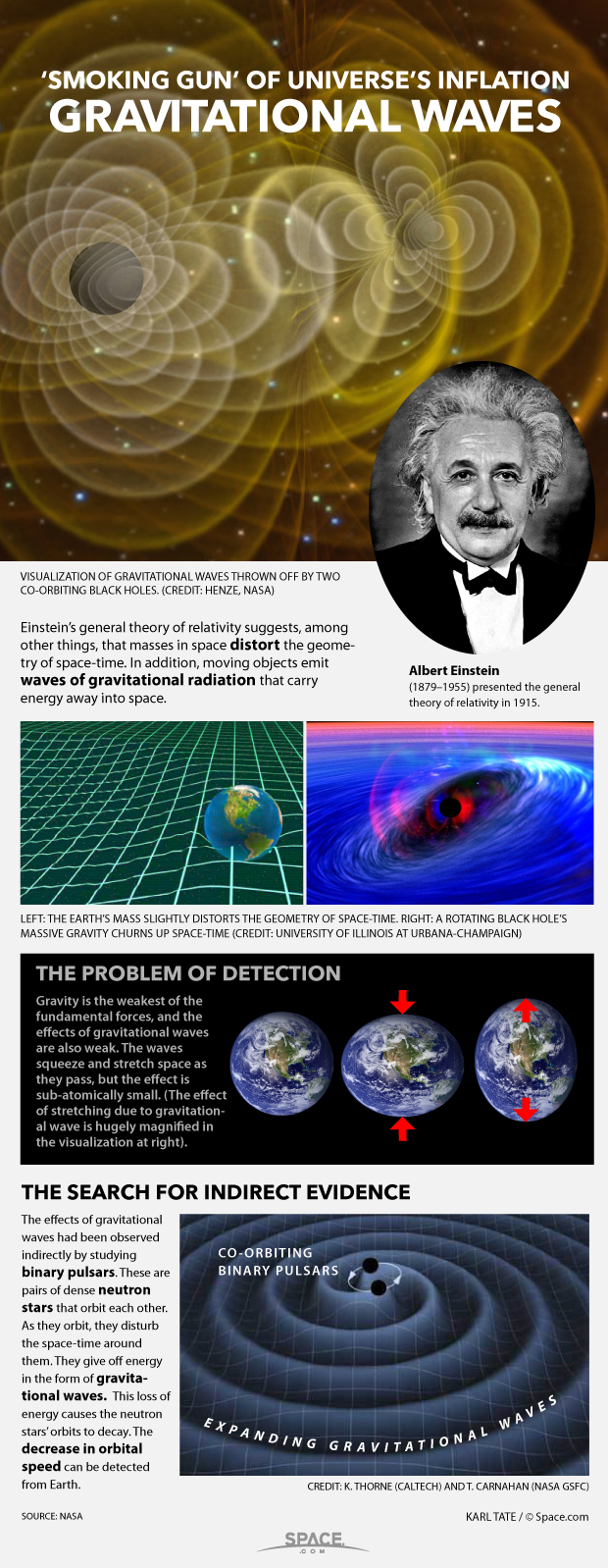

If the finding of these ripples, or primordial gravitational waves, is confirmed, it would represent the best evidence yet for inflation, the idea that the universe underwent an explosive burst in size in the earliest fractions of a second after the Big Bang. If the findings are discounted, inflation could still be correct, but scientists must provide other evidence.

A panel of well-known cosmologists debated the discovery and the model of cosmic inflation itself at an event here on Friday (May 30) at the World Science Festival, moderated by theoretical physicist Brian Greene of Columbia University in New York. [The Big Bang to Now in 10 Easy Steps]

A rapid expansion

One of the panelists, cosmologist Alan Guth of MIT, developed the hypothesis of inflation in 1980 to explain the large-scale structure of the universe. Another panelist, cosmologist Andrei Linde of Stanford University, helped develop the model of inflation.

The Big Bang left behind remnant heat, known as the cosmic microwave background (CMB). Radio astronomer Robert Wilson, who was in the audience, discovered the CMB along with physicist Arno Penzias in 1964. The CMB contains tiny temperature variations, but is remarkably uniform, which might be expected if the universe expanded from a very small region.

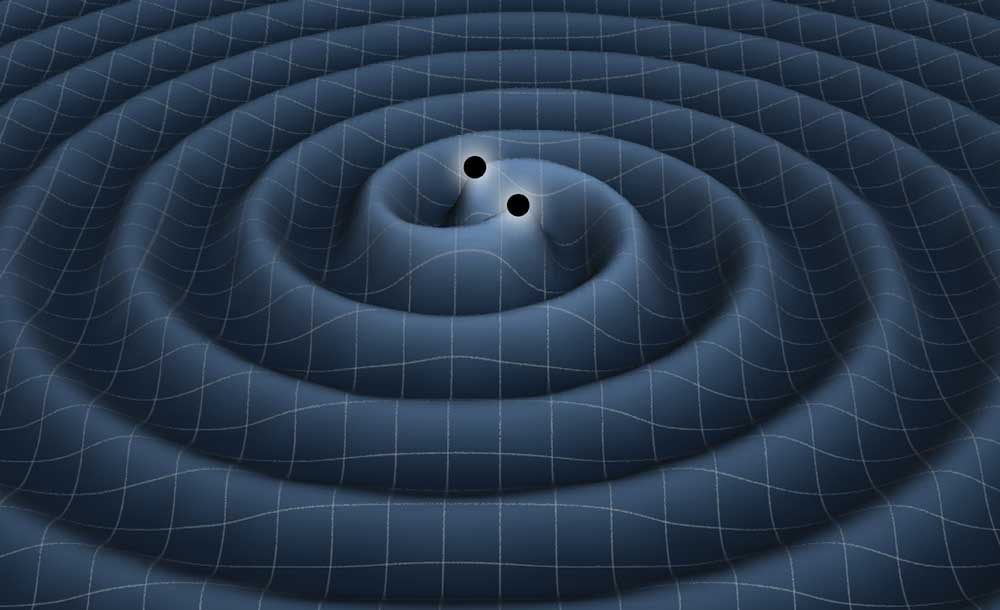

If inflation occurred, scientists suspect it might have left an imprint on the CMB, produced by gravitational waves, which would appear as a swirly pattern in the CMB. John Kovac, an astronomer at Harvard University — another of the panelists — and colleagues claimed to have detected this pattern in March using the BICEP2 instrument at the South Pole.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But since Kovac's team announced its findings, the results have come under fire from scientists who question whether the team had ruled out other possible sources that would produce the same swirly signature, such as galactic dust. In fact, two independent analyses of the data now suggest it could be accounted for by dust in the Milky Way.

In the panel discussion, Kovac admitted some uncertainty, but defended the findings. "The pattern is not there by random chance," Kovac said. His team has further analyzed their data and feels "very confident" the results were not spurious, he said.

But not everyone took the controversy lightly, including cosmologist Paul Steinhardt of Princeton University, who helped develop the model of inflation but now believes in an alternative model of the universe that suggests the existence of higher dimensions. Steinhardt took issue with how Kovac's team characterized their findings in March, saying that they were too confident in their statements at the time.

Other groups are also looking for these ripples from the Big Bang, including balloon-based and space-based telescopes. The European Space Agency's Planck satellite is expected to release its own data very soon, possibly in the next three weeks, and should offer strong evidence one way or the other.

Exciting times

Despite having helped develop it, Steinhardt now questions inflation itself. He said the theory was in some ways not falsifiable, which veers closer to the realm of metaphysics.

But inflation is still the most widespread theory for how the universe began, Alan Guth said. Andre Linde compared inflation to democracy, which has been called "the worst form of government there is, except for all the other forms."

As the evening panel concluded, Linde steered the discussion to a more hopeful note, about what it means to be a part of the endeavor to understand the universe in these times.

"There's something very exciting happening right now," he said.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.