Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

The universe is expanding faster than expected, suggesting that astronomers may have to incorporate some new physics into their theories of how the cosmos works, a new study reports.

The revised expansion rate is about 10% faster than that predicted by observations of the universe's trajectory shortly after the Big Bang, according to the new research. The study also significantly reduces the probability that this disparity is a coincidence, from 1 in 3,000 to just 1 in 100,000.

"This mismatch has been growing and has now reached a point that is really impossible to dismiss as a fluke," study lead author Adam Riess, a professor of physics and astronomy at The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, said in a statement.

"This is not what we expected," said Riess, who won the Nobel Prize for physics in 2011 (along with Brian Schmidt and Saul Perlmutter) for showing, in the late 1990s, that the universe's expansion is accelerating. It's unclear what's driving this surprising acceleration, but many astronomers invoke a mysterious, repulsive force called dark energy.

Related: The Universe: Big Bang to Now in 10 Easy Steps

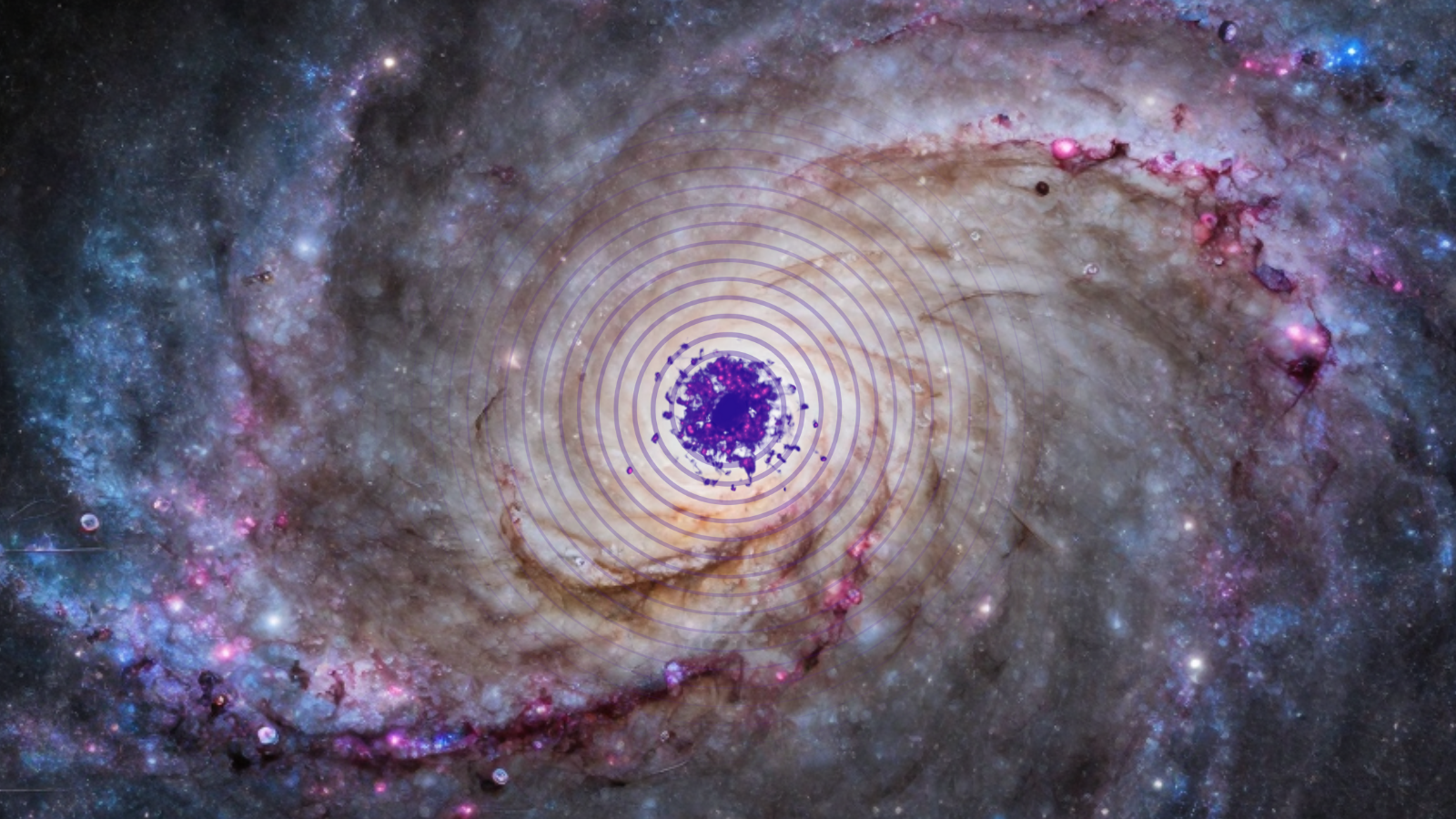

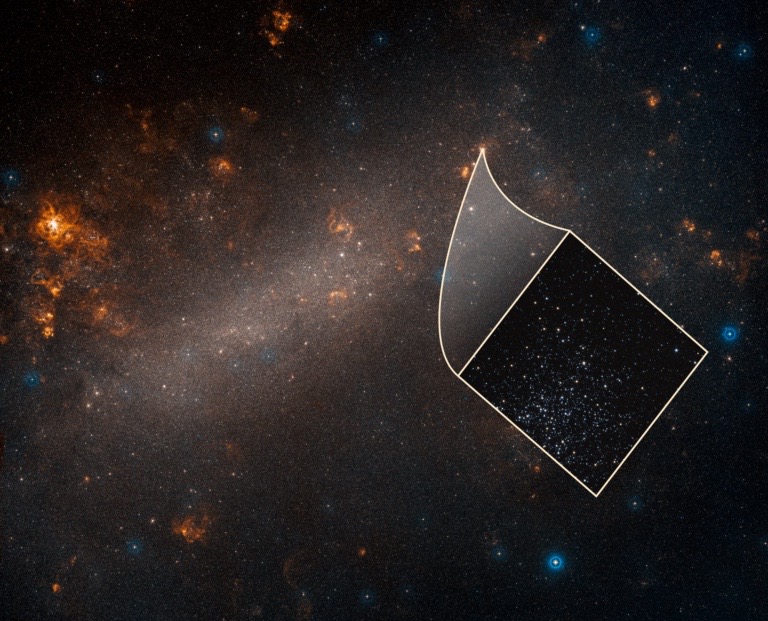

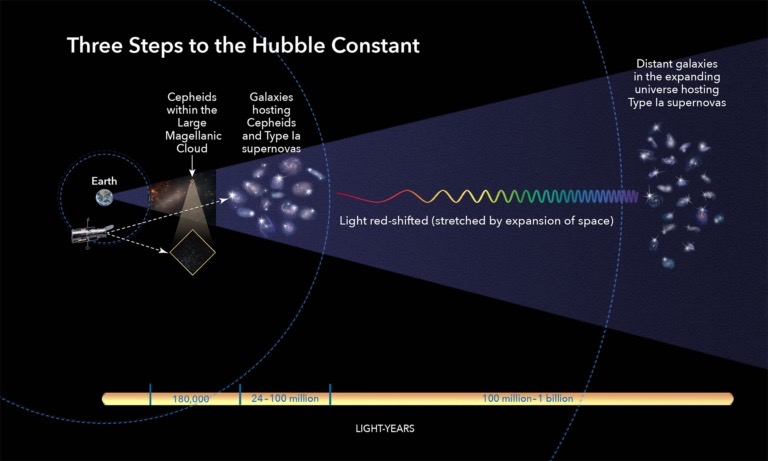

In the new study, Riess and his colleagues used the Hubble Space Telescope to study 70 Cepheid variable stars in the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), one of the Milky Way's satellite galaxies. Cepheid variables dim and brighten at predictable rates and are therefore "standard candles" that allow astronomers to calculate distances.

(Another kind of standard candle, the star explosions known as Type 1a supernovae, enables scientists to measure distances even farther out into space. Riess, Schmidt and Perlmutter's studies of Type 1a supernovae led to their Nobel-winning discovery.)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Riess and his team also incorporated observations made by the Araucaria Project, a collaboration involving researchers in the United States, Europe and Chile, who studied various LMC binary star systems, noting the dimming that occurred when one star passed in front of its neighbor. This work provided additional distance measurements, helping the study team to improve their understanding of the Cepheids' intrinsic brightness.

The researchers used all of this information to calculate the universe's present-day expansion rate, a value known as the Hubble constant, after American astronomer Edwin Hubble. The new number is about 46.0 miles (74.03 kilometers) per second per megaparsec; one megaparsec is roughly 3.26 million light-years.

The uncertainty attached to this number is just 1.9%, the researchers said. That's the lowest uncertainty value to date that has been calculated using this approach — down from about 10% in 2001 and 5% in 2009.

The "expected" expansion rate, by contrast, is about 41.9 miles (67.4 km) per second per megaparsec. This projected rate is based on observations that Europe's Planck satellite made of the cosmic microwave background – the light left over from the Big Bang that created the universe 13.82 billion years ago.

"This is not just two experiments disagreeing. We are measuring something fundamentally different," Riess said.

"One is a measurement of how fast the universe is expanding today, as we see it. The other is a prediction based on the physics of the early universe and on measurements of how fast it ought to be expanding," he added. "If these values don’t agree, there becomes a very strong likelihood that we’re missing something in the cosmological model that connects the two eras."

The new study was published today (April 25) in The Astrophysical Journal. You can read it for free at the online preprint site arXiv.org.

- Our Expanding Universe: Age, History & Other Facts

- Hubble in Pictures: Astronomers' Top Picks (Photos)

- Types of Variable Stars: Cepheid, Pulsating and Cataclysmic

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.