Faint Filaments of Universe-Spanning 'Cosmic Web' Finally Found

Most of the hydrogen formed during the Big Bang resides in these threads.

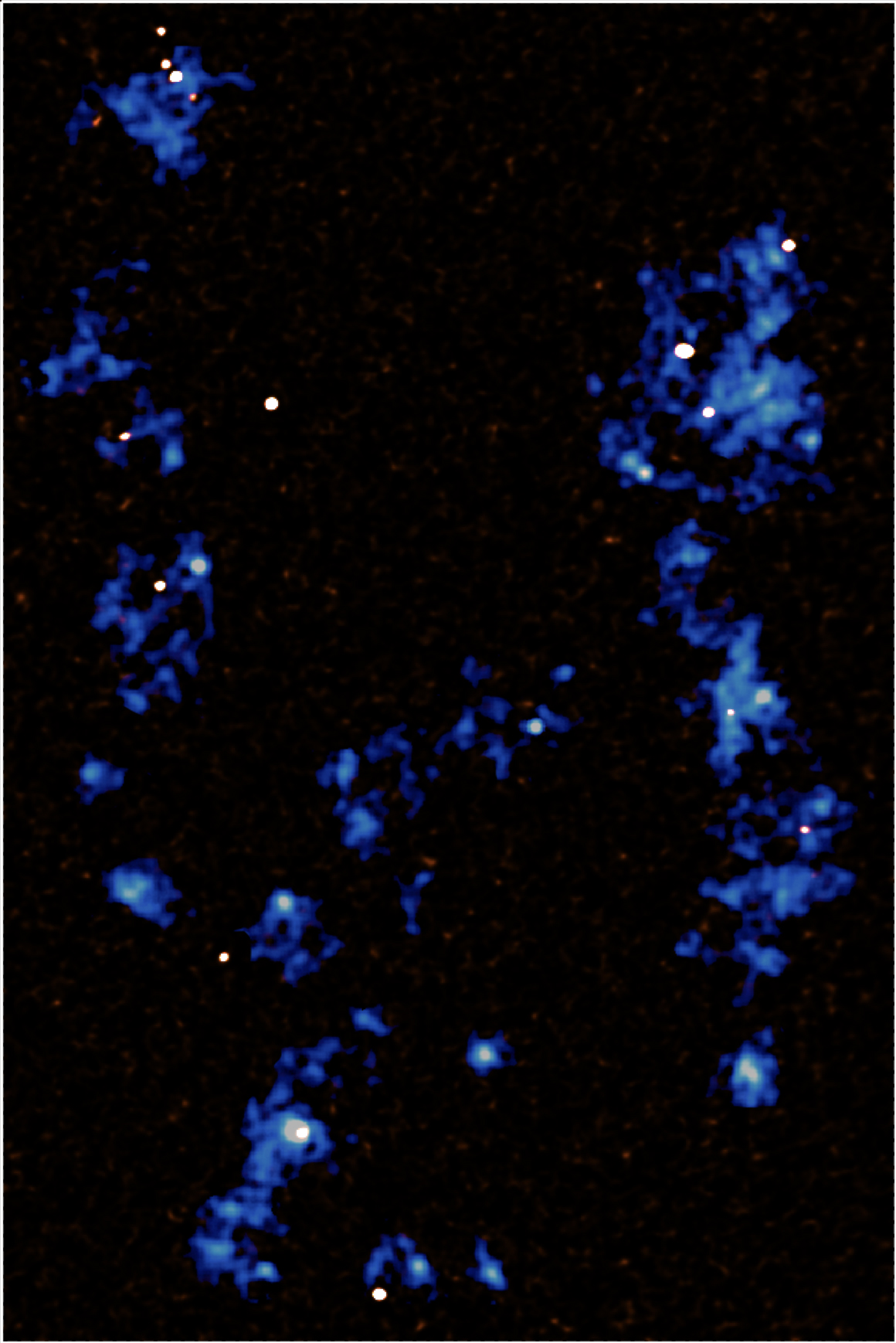

The faintly glowing wisps of gas that make up the intergalactic filaments of a universe-spanning cosmic web may have finally been detected for the first time, a new study reports.

This gas is apparently helping fuel the growth of young galaxies, shedding light on how the universe has evolved over time, researchers said.

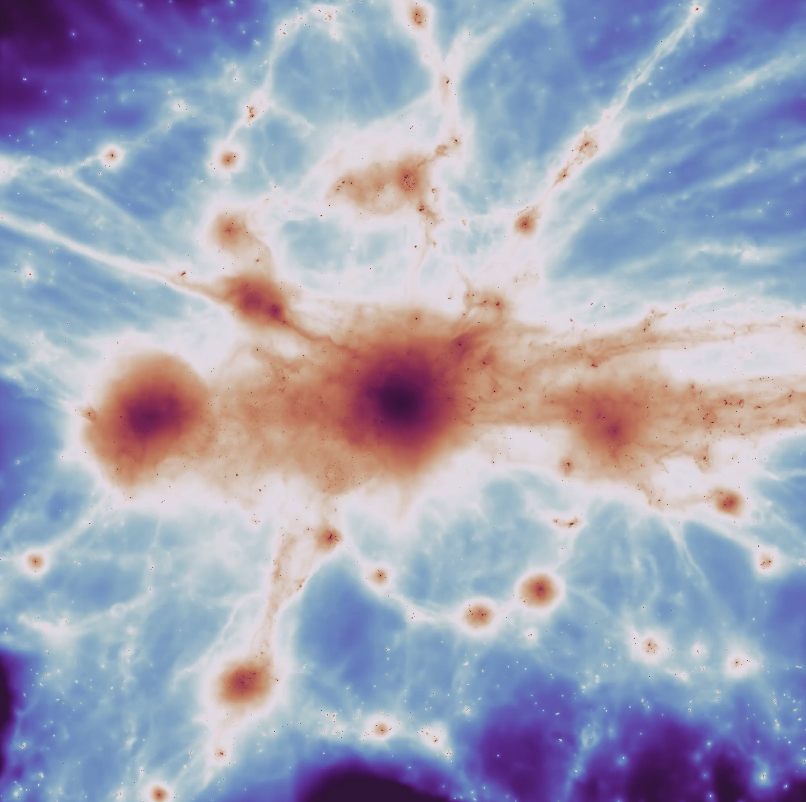

Previous research suggests that, after the universe was born in the Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago, much of the hydrogen gas that makes up most of the known matter of the cosmos collapsed to form colossal sheets. These sheets then broke apart to form the filaments of a vast cosmic web.

Related: The Universe: Big Bang to Now in 10 Easy Steps

Cosmological simulations have predicted that more than 60% of the hydrogen created during the Big Bang lies within these giant filaments. Prior work also indicates that, where these filaments cross, galaxies form and are fed by rivers of gas.

Much of the evidence for the cosmic web has remained circumstantial, however. Direct observations of these filaments have remained elusive because the gas within them is barely detectable.

Now astronomers have directly detected the cosmic web with the help of intense light from young, star-forming galaxies.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"I originally did not expect to see such cosmic web filaments ... they were thought to be much fainter and very hard to see," study lead author Hideki Umehata, an astronomer at the RIKEN Cluster for Pioneering Research in Saitama, Japan, told Space.com.

The scientists focused on the SSA22 Protocluster, which lies about 12 billion light-years away from Earth in the constellation Aquarius. A protocluster is a group of hundreds to thousands of galaxies that are beginning to form a galaxy cluster, the largest structures held together by gravity in the universe.

Using the Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer instrument on the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope in Chile, the researchers detected and mapped light emitted by hydrogen gas excited by ultraviolet rays from galaxies within the protocluster. The instrument was designed to scan wide swaths of the sky to spot the faintest structures known.

"The main obstacle to see the filaments is their faintness," Umehata said. "To circumvent this, one can turn to a region where the filaments are much brighter than the usual case. In this work, we focus on a core of the protocluster where a number of star-bursting galaxies illuminate the filaments."

Essentially, the core of the protocluster acted like a flashlight to help illuminate the otherwise elusive filaments of the cosmic web.

Gas around the young galaxies in the protocluster was arranged in long filaments extending over more than 3.25 million light-years, the scientists found in the new study, which was published online today (Oct. 3) in the journal Science.

These strands are the brightest threads of the cosmic web found yet, but they're still quite dim. The emission levels from the very outskirts of the filaments are as low as 5% that of the ambient background light from the rest of the sky, said astrophysicist Erika Hamden at the University of Arizona in Tucson, who wrote a commentary piece about the new study in the same issue of Science.

"These gaseous structures were predicted for years theoretically, but astronomers have struggled to map them directly," Umehata said. "Our work shows that mapping cosmic web filaments is now possible, which means that we have obtained a novel tool to understand the formation of galaxies and supermassive black holes."

These filaments are likely feeding gas to the protocluster. "They are thought to fuel the intense activity seen in galaxies — star formation and the growth of supermassive black holes," Umehata said. "Thus, our research adds a key piece to understand how galaxies and supermassive black holes acquire their fuels."

- Neutrinos Entangled in the Cosmic Web May Change the Structure of the Universe

- Our Expanding Universe: Age, History & Other Facts

- The Universe Is Expanding So Fast We Might Need New Physics to Explain It

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us