'Terminator Tape' did its job in space-junk test — and it will be back

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

One technique that could help alleviate the space-junk scourge just passed a key off-Earth test.

In June 2019, SpaceX's huge Falcon Heavy rocket launched two dozen satellites to Earth orbit, including a 154-lb. (70 kilograms) craft called Prox-1 that was built by a team based at the Georgia Institute of Technology. Shortly thereafter, Prox-1 successfully deployed The Planetary Society's solar-sailing LightSail 2.

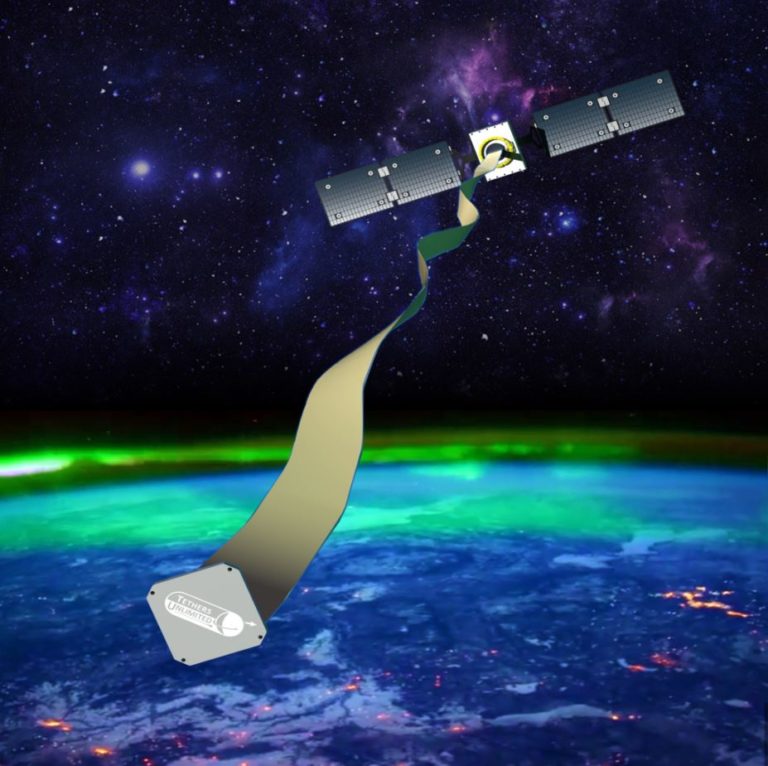

But Prox-1 wasn't done. In early September, the satellite performed another deployment: It activated the "Terminator Tape," a notebook-sized module attached to Prox-1's exterior. The module, built by Washington-based Tethers Unlimited, unfurled a 230-foot (70 meters) strip of electrically conductive tape designed to lower Prox-1's orbit via increased drag.

Related: Space Junk Explained: The Orbital Debris Threat (Infographic)

And the Terminator Tape did its job, Tethers Unlimited representatives said.

"Three months after launch, as planned, our timer unit commanded the Terminator Tape to deploy, and we can see from observations by the U.S. Space Surveillance Network that the satellite immediately began de-orbiting over 24 times faster [than before]," Tethers Unlimited CEO Rob Hoyt said in a statement last week.

"Rapidly removing dead satellites in this manner will help to combat the growing space debris problem," Hoyt added. "This successful test proves that this lightweight and low-cost technology is an effective means for satellite programs to meet orbital debris mitigation requirements."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Space junk poses a significant threat to the use and exploration of the final frontier, many experts have stressed. That threat is only increasing as it becomes easier and cheaper to build and launch satellites to orbit. With more spacecraft flying around up there, controlled by people of varying levels of operational experience, the chance of a collision will continue to rise. And even just a few in-space smashups might create a debris cascade that renders certain orbital regions unusable for the foreseeable future.

So, people like Hoyt and his team are devising ways to help bring satellites down in a timely fashion when their operational lives are over. Some of this tech would accompany satellites to orbit, as the Terminator Tape and similar drag-inducing sails have done. Other groups are developing junk-hunting spacecraft that would capture their quarry with harpoons or nets.

The Terminator Tape testing is not done yet. Tethers Unlimited is working with the companies Millennium Space Systems, TriSept Corp. and Rocket Lab on a mission called Dragracer, which will compare the deorbiting of two satellites that are identical in every way but one: One craft will sport a Terminator Tape module, and the other will not.

- See Stunning Photos of SpaceX Falcon Heavy's First Night Launch

- 7 Wild Ways to Clean Up Space Junk

- Latest News About Space Junk and Orbital Debris

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.