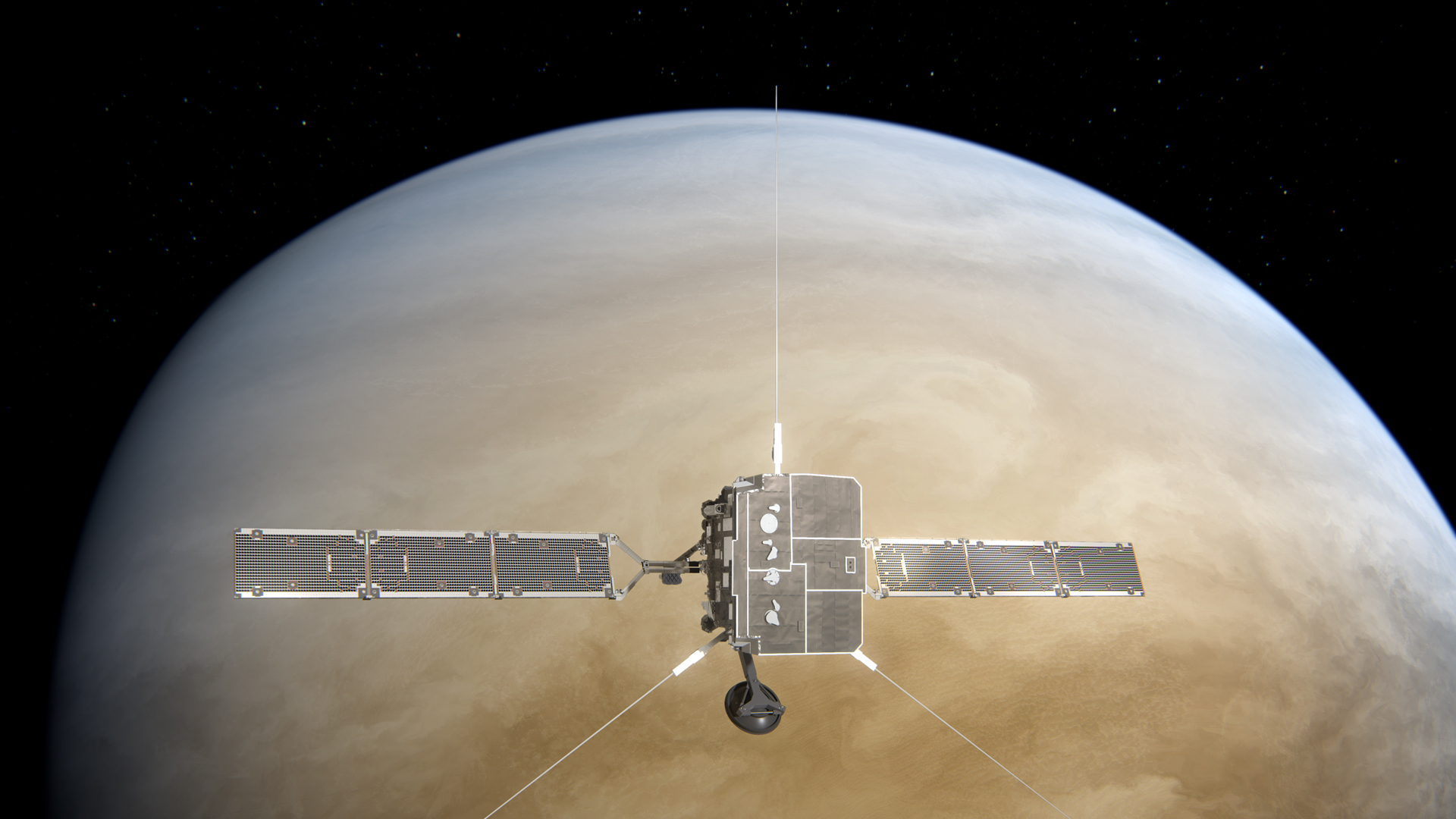

Solar Orbiter to look at Venus' magnetic field as it swings by the planet

"It is very interesting 'bonus science' enabled by Solar Orbiter's orbit design."

The sun-studying Solar Orbiter spacecraft will swing by Venus on Saturday (Sept. 3) and gather bonus observations of our neighbor planet's mysterious magnetic field.

The Solar Orbiter mission, led by the European Space Agency (ESA), is already capturing the closest-ever images of the sun. Throughout its lifetime, the probe uses the gravity of Venus to adjust its orbit and sneak closer to our star. These regular swings past the hot and scorching planet also enable Solar Orbiter to look at the mysterious magnetic field of Earth's planetary sister.

Today's flyby will see Solar Orbiter make its closest approach at 9:26 p.m. EDT (0126 GMT on Sept. 4), coming as close as 4,000 miles (6,400 kilometers) to Venus.

During the maneuver, one of the probe's instruments will be taking measurements of Venus' bow shock, Daniel Muller, ESA's Solar Orbiter project scientist told Space.com in an email. A bow shock is the sun-facing region of a planet's magnetic field, where it meets the solar wind, the stream of charged particles emanating from the sun.

"It is very interesting 'bonus science' enabled by Solar Orbiter's orbit design, and we are doing all we can to exploit it," Muller wrote.

Related: Solar Orbiter spacecraft captures huge eruption on the sun (video)

The upcoming flyby will be Solar Orbiter's third of Venus; the previous encounters also offered observations of the planet's magnetism. Unlike Earth, Venus doesn't have an inherent magnetic field generated by the motion of molten metal in the planet's interior. Instead, Venus' magnetic field is what scientists call an induced magnetic field, a result of the interaction between Venus' thick atmosphere and the solar wind.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Measurements obtained during the previous Venus flybys in December 2020 and August 2021 revealed that on the side of Venus facing away from the sun, the magnetic field, although extremely weak, extends at least 188,000 miles (300,000 km) into space. Solar Orbiter also found that despite its weak and unstable nature, the magnetic field accelerates charged particles within Venus' magnetosphere to speeds of over 5 million mph (8 million kph).

Scientists have known Venus' magnetic field existed since the first spacecraft visited the planet in the 1960s and 1980s. There are, however, still many unanswered questions about the field's origins and behavior.

Solar Orbiter, which launched in 2020, will have several more opportunities to contribute to answering those questions. The probe will return to Venus eight times over nearly a decade during its travels in space to use the planet's gravity to shift its orbit out of the ecliptic plane, in which planets orbit.

These maneuvers will eventually allow the spacecraft to view the sun's poles, which are so far completely unexplored. The polar regions are critical to generating the sun's magnetic field, which in turn drives the sun's 11-year-cycle of activity, the ebb and flow in the creation of sunspots, eruptions and flares. The exact mechanism behind this cycle and its varying intensity remains unknown.

Solar Orbiter will have the best chance to answer these questions as it studies the star just as its activity builds up toward the peak of the current solar cycle, predicted to occur around 2025.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.