Satellites reveal catastrophic year for emperor penguins amid climate crisis in Antarctica (photos)

"Their breeding success has been really impacted by the lack of sea ice."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Satellite images have revealed horrific emperor penguin carnage in climate change-stricken Antarctica as sea ice melted underneath the birds' colonies last year, leaving helpless chicks to drown in frigid waters.

The Antarctic spring of 2022 may have been the worst in history for the magnificent emperor penguins that inhabit the frozen continent. As sea ice broke up beneath their feet at a speed never seen before, colony after colony was left in tatters as chicks, too young to survive in the ice-cold waters, drowned or froze to death.

Researchers at the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) observed the tragedy as it unfolded in satellite images and have now shared their findings in a new study.

Related: Climate change hits Antarctica hard, sparking concerns about irreversible tipping points

"Emperor penguins are having a particularly bad year this year," Peter Fretwell, a remote-sensing scientist at the BAS and lead author of the study, told Space.com in an interview. "Their breeding success has been really impacted by the lack of sea ice."

Fretwell has been studying remote colonies of emperor penguins using satellite images for the last 15 years. These imposing birds, the tallest of all penguin species, inhabit the harshest environments on Earth. Adapted to withstand temperatures as low as minus 76 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 60 degrees Celsius), the penguins breed on sea ice, where they live in colonies of hundreds of individuals. Fretwell and his team have previously witnessed what sea ice loss can do to these colonies. In 2016, 2017 and 2018, a large colony in Halley Bay lost almost all of its chicks when warmer-than-usual weather decimated the sea ice.

"The emperor penguins have a unique breeding cycle, and it breeds in the Antarctic winter rather than the summer," Fretwell said. "It needs sea ice and it needs the sea ice to be stable between April and December, because when it lays an egg and the chick hatches, the chick needs to have a stable platform to live on."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Covered only in fluffy down, penguin chicks can't swim and fish for food until they develop their outer waterproof jacket. This usually happens in December, about three months after the chicks hatch. Until then, the chicks fully depend on their doting parents to feed them and huddle together on the floating ice to keep warm while their parents fish. If the ice underneath the colony disintegrates too early in the season, the chicks stand no chance. They drown or freeze to death.

"This year, that happened to a lot of colonies," said Fretwell. "Many more this year than we've ever seen before."

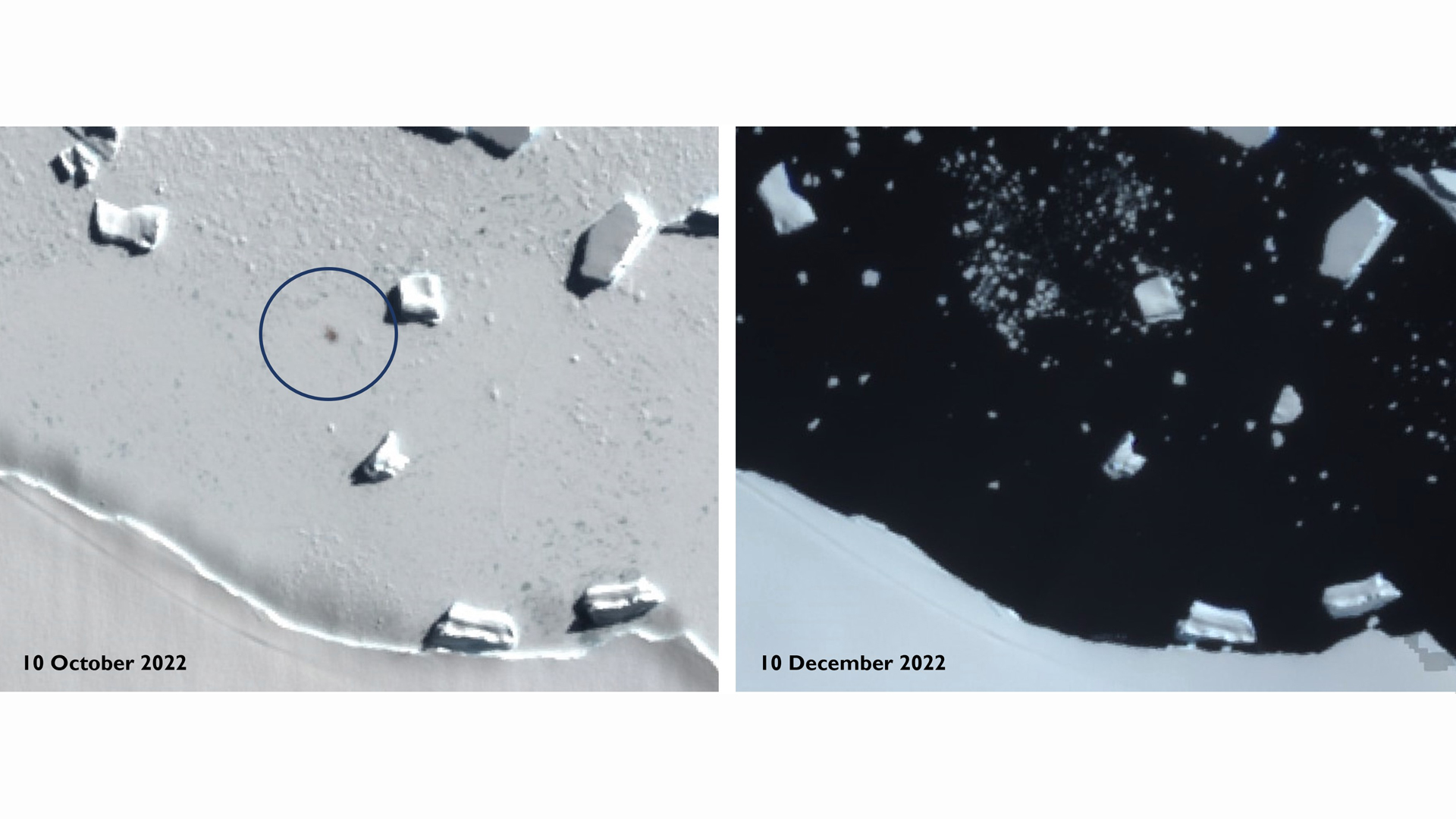

Satellite images taken by the European Earth-observation satellite Sentinel-2 revealed that all colonies in the Bellingshausen Sea in the west of Antarctica lost nearly all of their young ones.

"In this area, we've got maybe between 5,000 to 10,000 breeding pairs," said Fretwell. "There should be 5,000 to 10,000 chicks there. There was one place where they did survive, but they still only had about 200 chicks."

Most of the emperor penguin colonies are only known thanks to satellite images, as the stately birds inhabit the harshest and most inaccessible places. Scientists can track those colonies thanks to brown spots the penguins' feces leave on the pristine ice. Thanks to the most cutting-edge satellites, those that offer resolutions of about 12 inches (30 centimeters), researchers can even distinguish individual adult birds.

The horror scientists witnessed last year is likely only the tip of the iceberg, as there are many smaller, less visible animal species that too depend on sea ice to survive and breed. Those species must have been hit equally hard by the record loss of sea ice that hit the continent in the Antarctic spring and summer of 2022 and 2023. For all these species, more hard years likely lie ahead.

"Our models suggest that, in a scenario where climate change continues as is at the moment, we will lose 90% of the [emperor penguin] colonies by the end of the century," said Fretwell. "How much they can continue after that is hard to tell."

Scientists are already bracing for another year of disasters. After hitting an absolute record low in February this year, sea ice around the coast of Antarctica failed to replenish as the continent moved into its winter months, remaining well below seasonal averages at an unprecedented low.

For years, Antarctica seemed to have held more steady against progressing climate change that has long visibly decimated its northern counterpart, the Arctic. In recent years, the effects of the warming climate have caught up with the ice cap covering the south pole, sparking concerns of irreversible tipping points.

Years of record-low sea ice extent not only harm the Antarctic fauna but also bode ill for the continent's glaciers that are growing more fragile year on year. The ruin of the Antarctic ecosystem will be felt worldwide through rising sea levels and altered ocean currents, which will make the planet more vulnerable to further warming.

The study was published in the journal Communications Earth & Environment on Thursday, Aug. 24.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.