With a little luck, we may soon be in for a fine meteor shower.

Circumstances this year will be nearly ideal for watching the annual Perseid meteor shower at its predicted maximum late on the night of Aug. 12-13. Many families on August vacations at dark, country sites discover these meteors on their own, and late-summer campers often pull their sleeping bags out of their tents to enjoy this "Old Faithful" shower.

The Perseids are one of the two strongest and most dependable annual meteor showers (the Geminids of December being the other). Earth's orbit carries us through the densest part of the Perseid meteoroid stream every year around Aug. 12, so these "shooting stars" appear almost like clockwork. Their rates, however, can vary a lot from year to year. An observer with a quick eye under a dark sky might typically see more than 60 Perseids per hour between midnight and dawn. Typically, during an overnight watch, the Perseids are capable of producing a number of bright, flaring and fragmenting meteors, which leave fine trains which can persist for several seconds or more in their wake.

Related: Perseid meteor shower 2023: When, where & how to see it

According to Margaret Campbell-Brown and Peter Brown in the "2023 Observer's Handbook" of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Earth is predicted to cut through the densest part of the Perseid stream sometime around 4 a.m. EDT on Sunday, Aug. 13. Such circumstances do not occur very often. The Perseid stream has a dense core that gives the shower a sharp peak that lasts only about eight or nine hours centered on this particular time. So North America, especially in the eastern parts, is optimally positioned to catch this year's peak.

As a result, the late-night hours of Saturday, Aug. 12, on through the first light of dawn on the morning of Sunday, Aug. 13, hold the promise of seeing a very fine Perseid display.

The moon, whose bright light almost totally wrecked last year's shower, will hardly do so this year. Unlike last year when it was full, this year it will be a lovely waning crescent, only 8-percent illuminated and just 3 days before the new moon. Moreover, it will not rise until around 3 a.m. local daylight time on the morning of Aug. 13. So, 2023 is indeed an opportune year for watching for the August Perseids.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Meteor basics

The source of the Perseid shower is comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle, which orbits the sun in a long, roughly 130-year ellipse. The comet sheds bits of its material each time it returns near the sun. This debris keeps traveling along near the comet's orbital path, creating a sparse "river of rubble" in space. These meteoroids of the Perseid stream range from sand grains to pebbles and have a consistency like bits of cigar ash. They ram into Earth's atmosphere at a speed of 40 miles (60 km) per second, creating incandescent trails of shocked, ionized air as they vaporize.

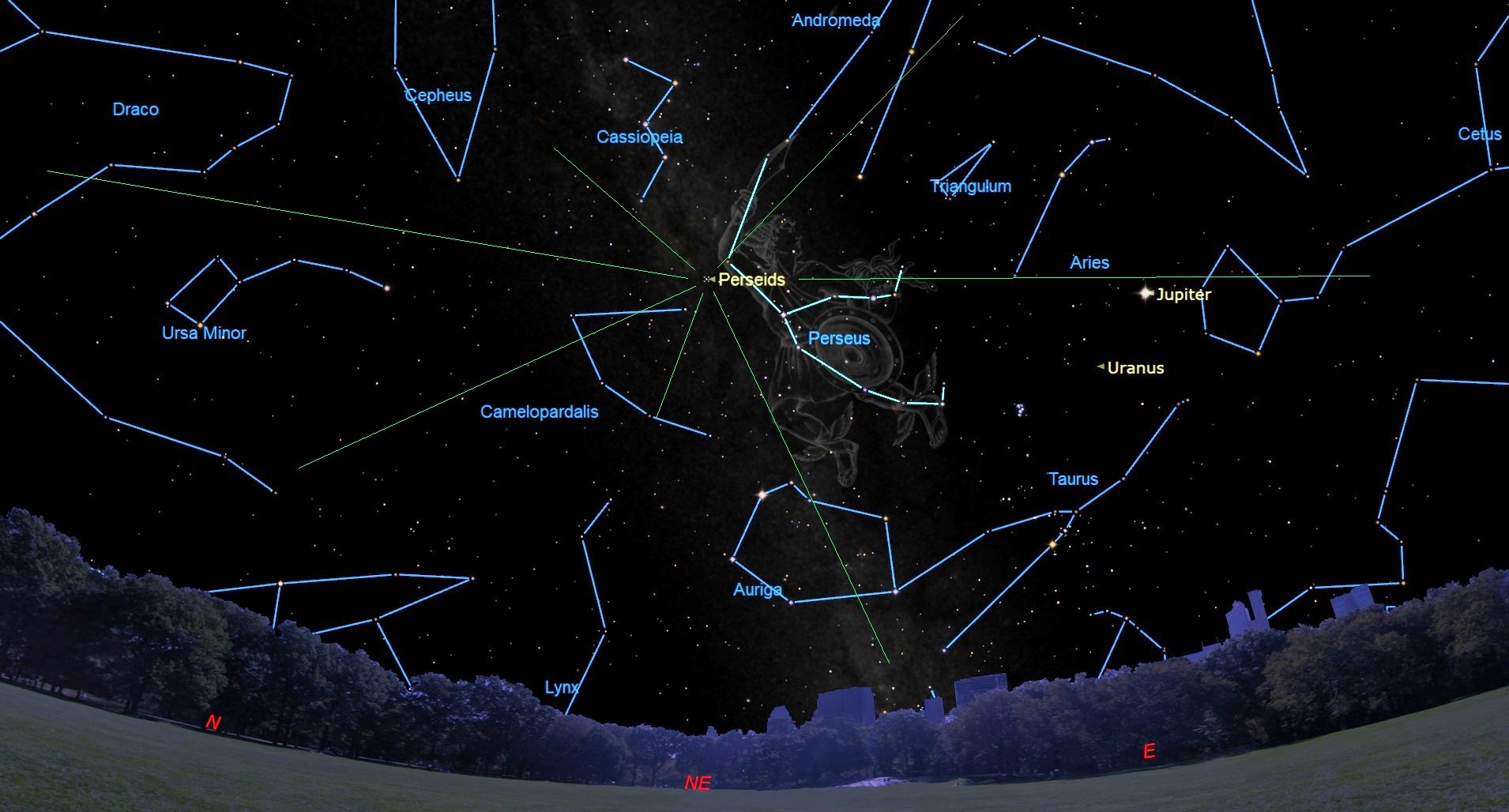

On the peak night, the Perseids will appear to diverge from a patch of sky between the Perseus and Cassiopeia constellations near to the famous Perseus Double Cluster. The meteors' apparent divergence from this radiant point is an effect of perspective; the meteoroids are actually traveling in parallel through space. Meteors appearing near the radiant will display short trails because we see them nearly head on, while those far from the radiant, are seen broadside, hence look much longer.

In the early-evening hours the radiant is low in the north-northeast, so the meteors strike the upper atmosphere at a low angle — and therefore we see comparatively few of them per square kilometer at the atmosphere's top. As the night advances, and as the radiant rises progressively higher in the northeast, the meteors arrive more nearly straight down, and we see more of them. Your clenched fist held at arm's length measures roughly 10 degrees in width in the sky. So, at the time of the break of dawn (around 4:30 a.m. local daylight time), the radiant has climbed to around 60 degrees ( or six fists) above the northeast horizon for observers at mid-northern latitudes.

How to watch

A very good shower like the Perseids will produce about one meteor per minute for a given observer under a dark country sky. Any light pollution or moonlight considerably reduces the count.

With this in mind, pick an observing site that's free of glary lights nearby, has a wide-open view of the sky, and preferably is as far as possible out from under city light pollution. Don't forget the mosquito repellent. Bundle up in blankets or a sleeping bag; you'll be surprised how quickly your body will lose heat when lying motionless for a long stretch of time, even in the summer.

Watching for meteors consists of lying back, gazing up into the stars, and waiting. Typically, the direction to watch is wherever your sky is darkest, usually straight up. For the Perseids, it is customary to watch the point halfway between the radiant (which will be rising in the northeast sky) and the point directly overhead (the zenith), though it's all right for your gaze to wander.

Making a meteor count is as simple as lying in a lawn chair or on the ground, and marking on a clipboard whenever a "shooting star" is seen. Record the beginning and ending times of each of your observing periods to the minute (making a time notation at least once an hour), and record the amount of any skywatching time lost to note-taking or breaks. (If you speak notes into a tape recorder, you'll never have to look away from the sky.) Also record the fraction of your visual sky view, if any, that is blocked by obstructions or occasional clouds.

Counts should be made on several nights before and after the predicted maximum, so the behavior of the shower away from its peak can be determined. Usually, good numbers of meteors should be seen on the preceding and following nights as well. The shower is generally at one-quarter-to-one-half strength one or two nights before and after maximum. A few Perseids can be seen as much as two weeks before and a week after the peak. The extreme limits, in fact, are said to extend from July 17 to Aug. 24, though an occasional one may be seen almost anytime during the month of August.

History

The earliest record of Perseid activity appears in the Chinese annals, where it is said that in 36 AD "more than 100 meteors flew thither in the morning." But in Medieval Europe, the Perseids were known as "The Tears of St. Lawrence."

Laurentius, a Christian deacon, is said to have been martyred by the Romans in 258 AD on an iron outdoor stove. It was in the midst of this torture that Laurentius supposedly cried out: "I am already roasted on one side and, if thou wouldst have me well cooked, it is time to turn me on the other."

The saint's death was commemorated on his feast day, August 10. King Phillip II of Spain built his monastery, the "Escorial," on the plan of the holy gridiron. And the abundance of shooting stars seen annually between approximately August 8 and 14 came to be known as St. Lawrence's "fiery tears."

No danger to watch

I'd like to conclude with a humorous anecdote that I've told before. It took place back in the early 1980's regarding a phone call that came into New York's Hayden Planetarium. The caller sounded very concerned about a radio announcement about an upcoming Perseid display and wanted to know if it would be dangerous to stay outdoors on the night of the peak of the shower (perhaps assuming there was a danger of getting hit).

But as we've already mentioned, the associated particles that produce the Perseid meteors are no bigger than sand grains or pebbles, and are consumed by atmospheric friction many dozens of miles above our heads. The caller was passed along to the Planetarium's Chief Astronomer, Dr. Kenneth Franklin, who assured the caller not to worry. "There are only two dangers from Perseid watching," he said. "Getting drenched with dew and falling asleep!"

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications.

Editor's Note: If you snap a photo of a meteor and would like to share it with Space.com's readers, send your photo(s), comments, and your name and location to spacephotos@space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.