NASA's adventurous Parker Solar Probe spacecraft zips past the sun again today

The spacecraft is putting the "sun" in "Sunday."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

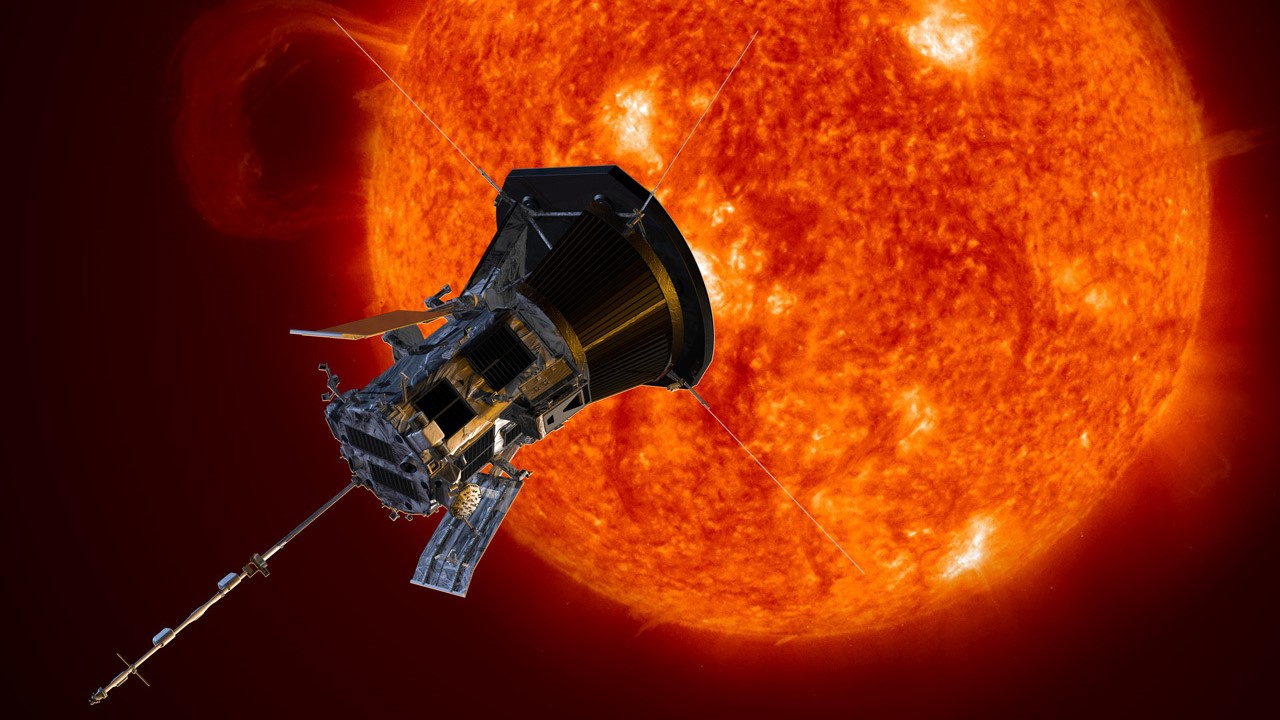

The Parker Solar Probe is making its 14th close flyby of the sun as part of its ongoing quest to unlock the mysteries of our star.

The NASA spacecraft will pass the sun's surface, also known as the photosphere, at a distance of around 5.3 million miles (8.5 million kilometers) on Sunday (Dec. 11), braving intense radiation and extreme heat to collect data regarding the star's outer atmosphere, the corona. The exact time of the closest approach to the sun, or perihelion, will be around 8:16 a.m. EST (1316 GMT), when the spacecraft will be traveling at an incredible speed of around 364,639 mph (586,829 kph).

Amazingly, this speed, 200 times faster than a bullet fired by a rifle, isn't the record velocity for the craft. On Nov. 21, 2021, the Parker Solar Probe achieved a slightly higher speed of 364,621 mph (586,000 kph) during its 10th solar flyby, becoming the fastest spacecraft ever built, although it will break that record later in its mission.

Related: What's inside the sun? A star tour from the inside out

The Dec. 11 perihelion won't be the closest for the Parker Solar Probe, which launched aboard a Delta IV-Heavy rocket from Cape Canaveral, in August 2018. During coming flybys, the spacecraft will advance on the sun, eventually passing as close as 3.8 million miles (6,115500 km) from our star's surface. Seven times closer to the sun than any previous craft and almost 10 times closer to the sun than the innermost planet, Mercury, this will see the Parker Solar Probe encounter temperatures as great as 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit (1,400 degrees Celsius).

To withstand these extreme conditions, the spacecraft is equipped with a 4.5-inch-thick (11.43 centimeters) carbon-composite shield that keeps its scientific payload at room temperature.

One of the Parker Solar Probe's primary objectives is to study the corona, the outermost layer of the sun's atmosphere, collecting data that could help solve one of the most long-standing mysteries regarding the sun: Why is its atmosphere hotter than its surface?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

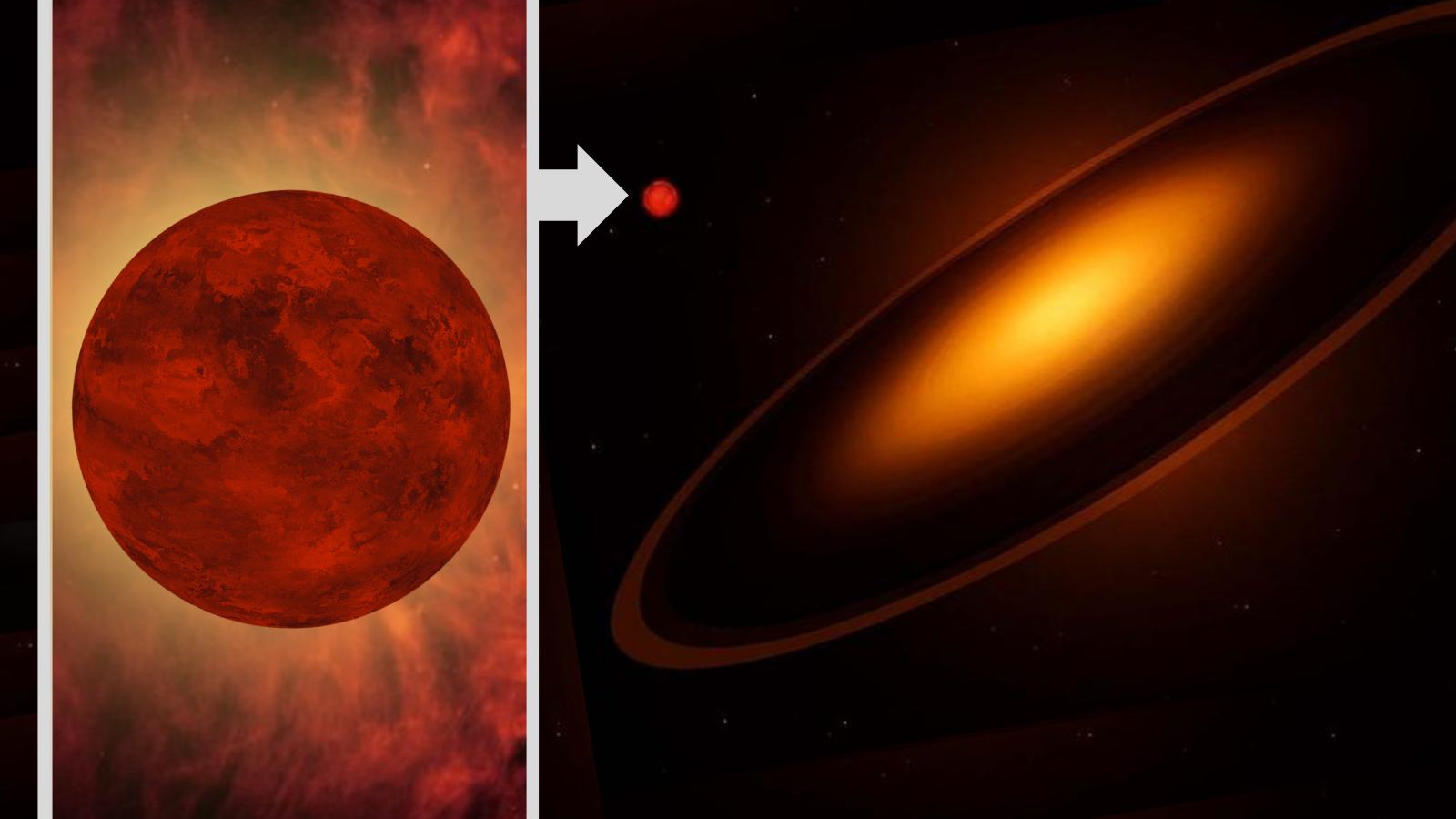

Theories of stellar physics suggest that deeper into the plasma of a star, the pressure increases and the star becomes hotter. The corona defies this wisdom, however. Despite being wispy and diffuse, the plasma in this layer is hotter than the plasma at the sun's surface, the photosphere that lies beneath the corona. Temperatures at the corona spike to 2 million F (1.1 million C) and higher, despite the fact that 1,000 miles (1,600 km) below it, the photosphere is 10 million times denser and reaches temperatures of just 10,000 F (5,500 C).

The corona is difficult to study from Earth because the light it emits is washed out by the much brighter light from the photosphere, meaning the corona is only visible during a total solar eclipse, when the moon blocks light from the photosphere. (Scientists can also use special tools to replicate the effect.)

Hence the need for the Parker Solar Probe to get "up close and personal" with our star in order to better understand the corona, which is also responsible for launching the solar wind, a stream of charged particles that can interfere with communication and power infrastructure here on Earth.

Because the sun is the only star close enough to study in this way, learning more about it will also help scientists understand stellar bodies much further afield.

The Parker Solar Probe will make its next and 15th close approach to the sun on March 17, 2023, also reaching around 5.3 million miles (8.5 million km) above the sun's surface. Later in the year, the spacecraft will swing past Venus to adjust its trajectory closer to the sun as the mission approaches its conclusion in 2025.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.