Eta Aquarid meteor shower 2023 peaking now! See pieces of Halley's Comet in the night sky

This annual meteor shower is created by debris left by Halley's comet as it makes its roughly 76-year orbit of the sun.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

The annual Eta Aquarids meteor shower peaks on Friday (May 5) and Saturday (May 6), offering skywatchers the opportunity to see debris from Halley's Comet as it enters Earth's atmosphere at incredible speeds and burns up.

This year the meteor shower began lighting up the night sky over Earth on April 19 and will last until May 28, so even after its peak there will be plenty of opportunity to catch fireballs streaking through the sky.

At its peak, the Eta Aquarid meteor shower has a rate of around 55 meteorites per hour, but this rate is calculated assuming perfect viewing conditions such as completely dark skies and ideal weather. This means skywatchers should realistically expect to see fewer Eta Aquarids meteors than this.

According to In the Sky, from New York City the Eta Aquarid meteor shower becomes visible each morning at around 2:32 a.m. EDT (0632 GMT) with it remaining active until around the break of dawn at 5:16 a.m. EDT (0916 GMT).

Related: Meteor showers 2023: Where, when and how to see them

Looking for a telescope to observe Aquarius or anything else in the sky? We recommend the Celestron Astro Fi 102 as the top pick in our best beginner's telescope guide.

Spotting the Eta Aquarids is even tougher in the Northern Hemisphere because the meteor shower's radiant, the point at which its meteors appear to stream, is located in the Aquarius constellation near one of the constellation's brightest stars, beta Aquarii, which only reaches a low altitude above the eastern horizon.

In the Northern Hemisphere, the Eta Aquarids' radiant is at its highest just before sunrise with it appearing over the horizon to the east for just a few hours. This makes the early dawn the best time to spot the most meteors. The reason why more meteors are visible when the radiant rises to its highest point, or "culminates," is because this is the time at which this region of Earth is turned towards the direction of incoming meteors.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This results in more meteors raining down vertically and creating short trails close to the star beta Aquarii. At other times, though meteors will be fewer, the fact they take more horizontal paths through Earth's atmosphere means they take longer to burn up, and as a result, these long-lived meteors create relatively stretched trails over Earth.

Skywatchers who can't make it outdoors to view the meteor shower during its peak have the option to watch it streamed online live and for free. The Asahi Shimbun Space Department and the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ) began a livestream of the Eta Aquariids from the Subaru Telescope, MaunaKea Hawaii, on April 18.

Like all meteor showers, the Eta Aquarids are created when Earth during its 365.25-day orbit of the sun passes through a cloud of dust and debris left by a comet or an asteroid. And the Eta Aquarids have a very famous progenitor indeed, arguably the most well-known comet, Halley's Comet, or more formally 1P/Halley.

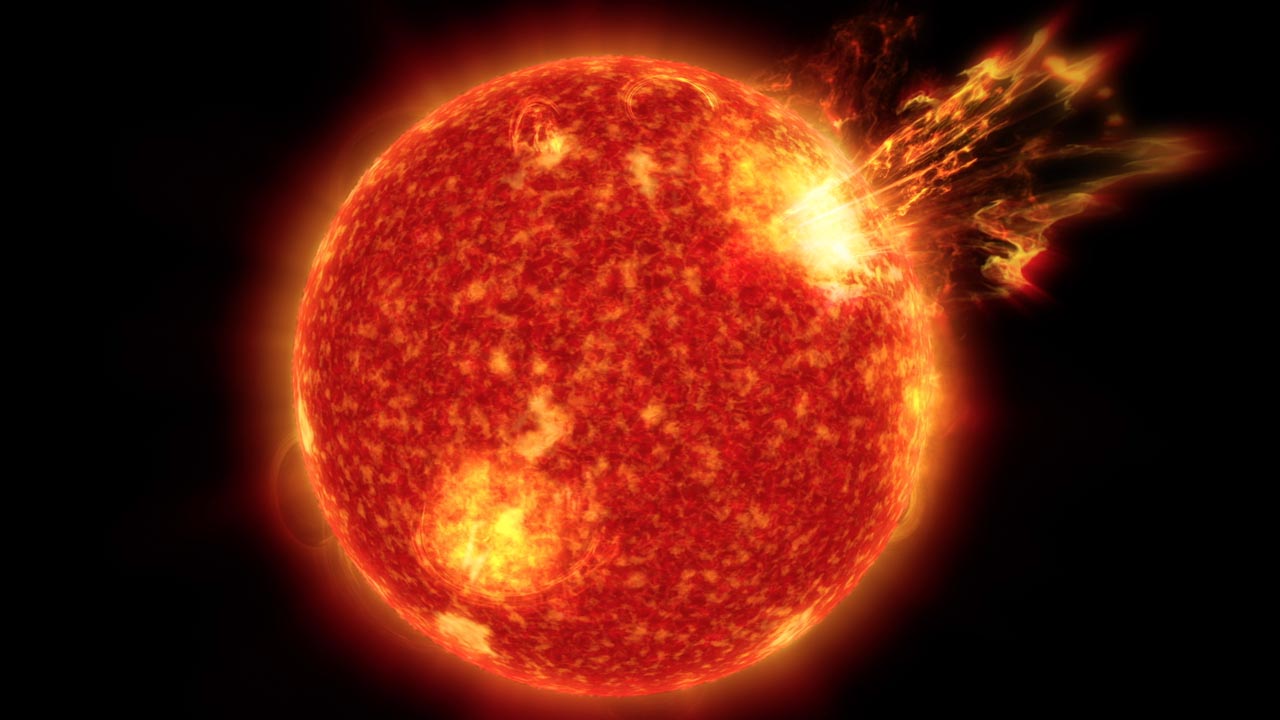

As comets come close to the sun, the radiation from our star causes the material that composes them to heat up. This results in solid ice within the cometary body transforming directly into gas, a process called sublimation. As this gas is ejected, it blasts away particles of dust and ice from the comet. This causes these icy bodies to brighten as they approach the sun and also gives them the characteristic glowing aura, or coma, that surrounds them and their cometary tail.

In addition to this, some fragments of this ejected material linger around the sun as the comet orbits, and as the Earth makes its own journey around its parent star, it passes through these clouds usually at the same time each year.

Our planet encounters debris from Halley's Comet every April to May, giving rise to the Eta Aquarids. These dust fragments separated from Halley's Comet hundreds of years ago, something scientists know because the current path of the comet doesn't seem to bring it close enough to the Earth to leave cometary debris that would create meteor showers.

The fragments enter Earth's atmosphere at speeds as great as 148,000 miles per hour, which is 100 times faster than a jet fighter, and burn up at altitudes of around 44 to 62 miles (70 to 100 kilometers) over the surface of the planet.

The last time Halley's Comet's 76-year orbit of the sun brought it past Earth was in 1986 and it won't be back until 2061, according to NASA. That means for the next 38 years, the closest skywatchers will get to observing the comet is sighting the debris it shed hundreds of years ago as it is destroyed in the atmosphere.

If you want to get a closer look at Aquarius to hopefully see some of the Eta Aquarids, our guides to the best telescopes and best binoculars are a great place to start.

And you're looking to snap photos of the night sky in general, check out our guide on how to photograph the moon, as well as our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

Editor's Note: If you catch a photograph of the Eta Aquarid meteor shower and would like to share it with Space.com's readers, send your photo(s), comments, and your name and location to spacephotos@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.