Scientists get more great looks at the 1st black hole ever photographed

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

The supermassive black hole at the heart of the galaxy M87 is coming into sharper and sharper focus.

Two years ago, astronomers with the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) project unveiled imagery of that black hole, which lies 55 million light-years from Earth and is as massive as 6.5 billion suns. Those photos were historic — the first direct views of a black hole that humanity had ever captured.

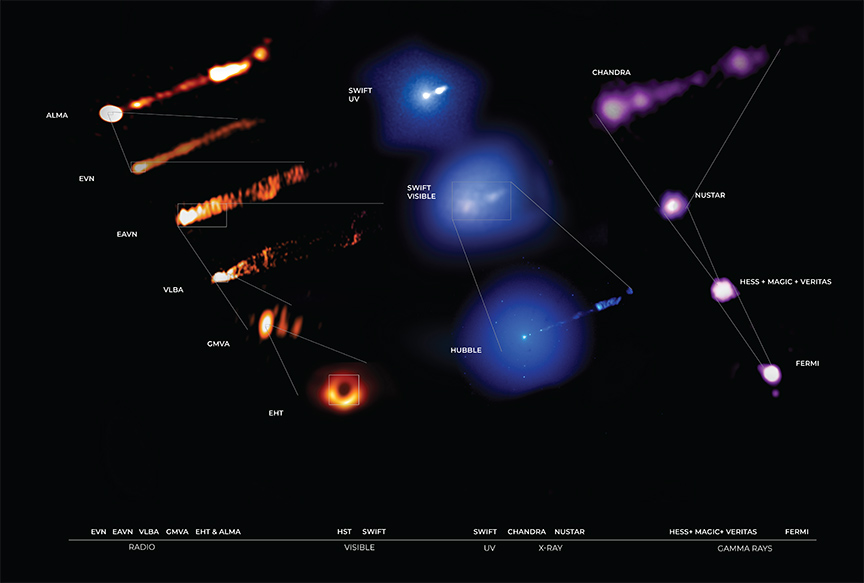

In the spring of 2017, as the EHT team was gathering some of the data that would result in the epic imagery, nearly 20 other powerful telescopes on the ground and in space were studying the M87 black hole as well.

Related: Historic first images of a black hole show Einstein was right (again)

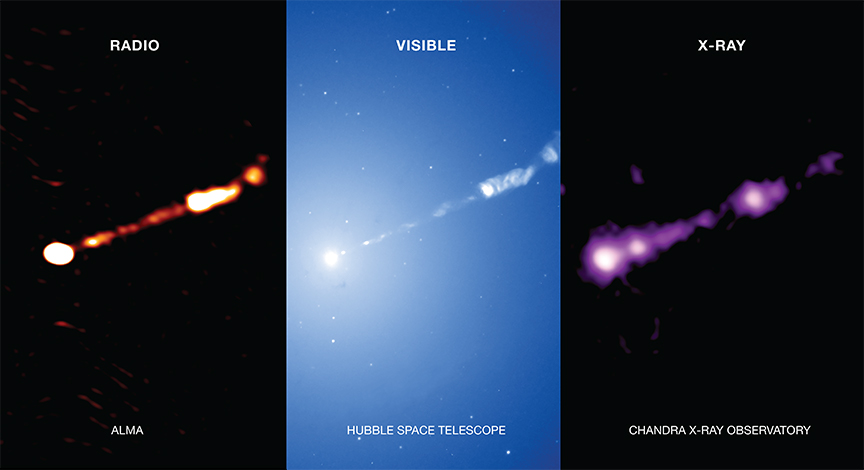

A new study describes this huge and powerful data set, which contains observations across a wide range of wavelengths gathered by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, Chandra X-ray Observatory, the Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, the Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array (NuSTAR) and Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, as well as a number of other scopes.

"We knew that the first direct image of a black hole would be groundbreaking," study co-author Kazuhiro Hada, of the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, said in a statement. "But to get the most out of this remarkable image, we need to know everything we can about the black hole's behavior at that time by observing over the entire electromagnetic spectrum."

That behavior includes the launching of jets, or beams of radiation and fast-moving particles rocketing outward from M87's black hole. Astronomers think such jets are the source of the highest-energy cosmic rays, particles that zoom through the universe at nearly the speed of light.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The new data set gathers the results of the most intensive simultaneous observing campaign ever undertaken on a black hole with jets, study team members said. So, plumbing it could yield key insights into jet dynamics and the origins of cosmic rays, among other things.

"Understanding the particle acceleration is really central to our understanding of both the EHT image as well as the jets, in all their 'colors,'" co-author Sera Markoff, an astrophysicist with the University of Amsterdam, said in the same statement.

"These jets manage to transport energy released by the black hole out to scales larger than the host galaxy, like a huge power cord," Markoff said. "Our results will help us calculate the amount of power carried and the effect the black hole's jets have on its environment."

The EHT, which links radio telescopes around the world to form a virtual instrument the size of Earth itself, is scheduled to begin observing the M87 black hole again this week after a two-year hiatus. The project gathers data only during a short window in the Northern Hemisphere spring each year, when the weather tends to be good at its various observing sites. Technical issues scuttled the 2019 campaign, and last year's was called off because of the coronavirus pandemic.

As in previous years, the new EHT campaign will also include observations of the supermassive black hole at the heart of our own Milky Way galaxy, a 4.3-million-solar-mass object known as Sagittarius A*. The new data could be even more revealing, because the EHT recently added three big scopes to its network — the Greenland Telescope, the Kitt Peak 12-meter Telescope in Arizona, and the Northern Extended Millimeter Array in France.

"With the release of these data, combined with the resumption of observing and an improved EHT, we know many exciting new results are on the horizon," study co-author Mislav Baloković, of Yale University, said in the same statement.

The new study, which gathers the work of 760 scientists and engineers from nearly 200 institutions across the globe, was published online Wednesday (April 14) in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.