James Webb Space Telescope glimpses Earendel, the most distant star known in the universe

The star's discovery by the Hubble Space Telescope was only announced earlier this year.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The James Webb Space Telescope has caught a glimpse of the most distant star known in the universe, which had been announced by scientists using Webb's predecessor the Hubble Space Telescope only a few months ago.

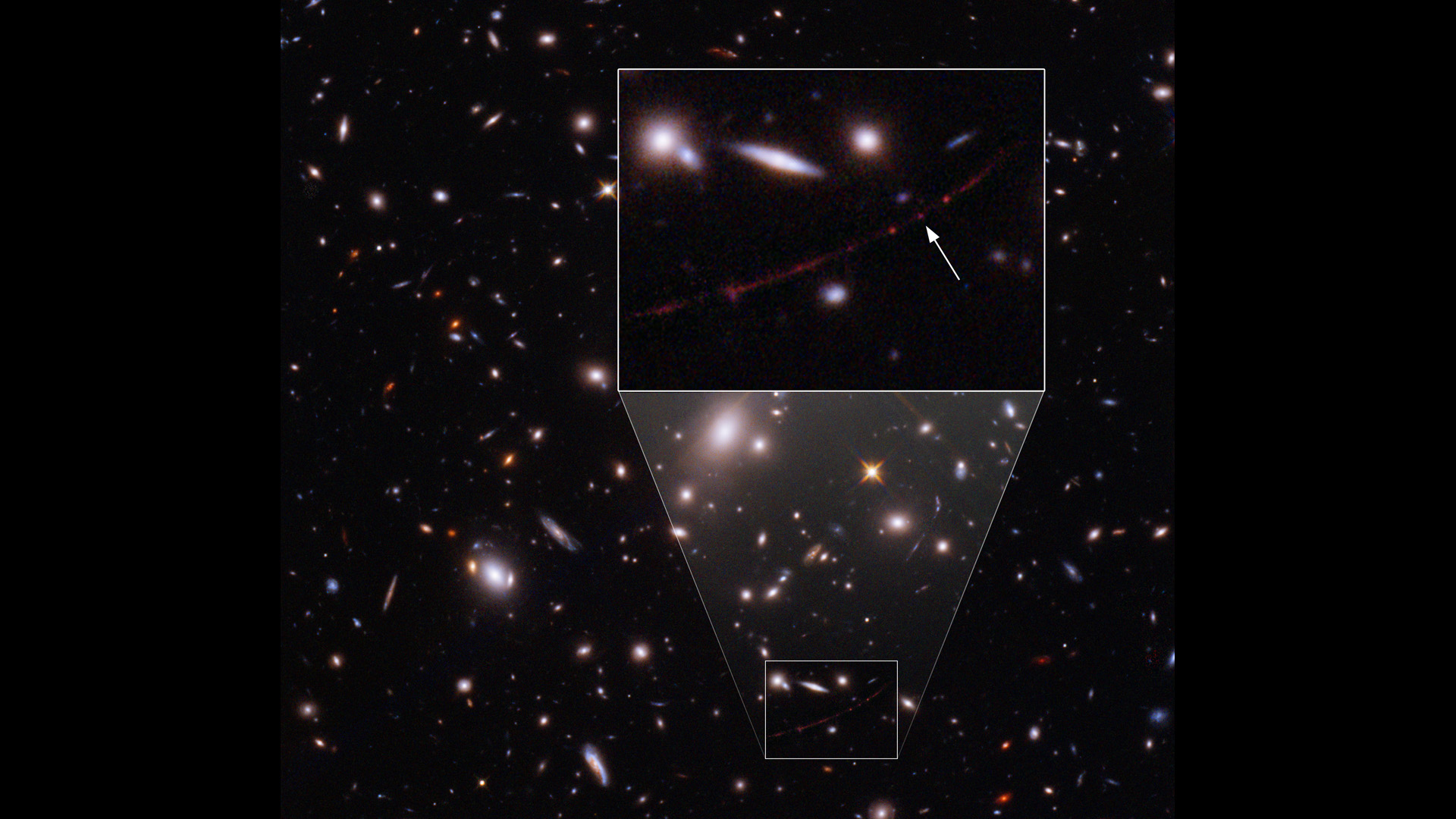

The star, named Earendel, after a character in J.R.R. Tolkien's "Lord of the Rings" prequel "The Silmarillion," was discovered thanks to gravitational lensing in a Hubble Space Telescope deep field image. The star, whose light took 12.9 billion years to reach Earth, is so faint that it might be rather challenging to find it in the new James Webb Space Telescope image, which was released on Twitter on Tuesday (Aug. 2) by a group of astronomers using the account Cosmic Spring JWST.

The original Hubble image provides some guidance as to where to look through the zoomed-in cut-out. Essentially, Earendel, is the tiny whitish dot below a cluster of distant galaxies. By comparing the Hubble image with that captured by Webb, you can find the elusive Earendel.

Gallery: James Webb Space Telescope's 1st photos

"We're excited to share the first JWST image of Earendel, the most distant star known in our universe, lensed and magnified by a massive galaxy cluster," the Cosmic Spring astronomers wrote in the tweet, noting that the observations occurred on Saturday (July 30).

The tweet refers to gravitational lensing, which is nature's help for astronomers. The effect takes advantage of the fact that extremely massive bodies, such as galaxy clusters or supermassive black holes, bend light from objects behind them. When light passes by such a body, it behaves as if it were passing through the lens of a telescope, becoming magnified, albeit also distorted. Using gravitational lensing therefore extends the reach of telescopes, such as Hubble and Webb, enabling them to see farther and in greater detail.

Webb was designed to see the first galaxies that sprung up in the young universe in the first hundreds of millions of years following the dark ages after the Big Bang. Astronomers, however, thought that it would not be possible to see individual stars of this first generation of suns that formed at that time. But gravitational lensing might actually enable them to see inside those early stellar groupings in detail.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"JWST was designed to study the first stars. Until recently, we assumed that meant populations of stars within the first galaxies," astronomers from the Space Telescope Science Institute in Maryland, which operates Webb and Hubble, wrote in a recent paper discussing the technique. "But in the past three years, three individual strongly lensed stars have been discovered. This offers a new hope of directly observing individual stars at cosmological distances with JWST."

Earendel, also known under its proper name WHL0137-LS, is located in the constellation of Cetus, but don't expect to see it if you look up at the night sky — even gravitational lensing isn't that powerful.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter at @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.