How NASA's Mars helicopter Ingenuity can fly on the Red Planet

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Update for April 19: Ingenuity successfully made its first flight on Mars. Read the full story here.

Flying on Mars is far from a breeze, but NASA is confident that its little helicopter is up to the challenge.

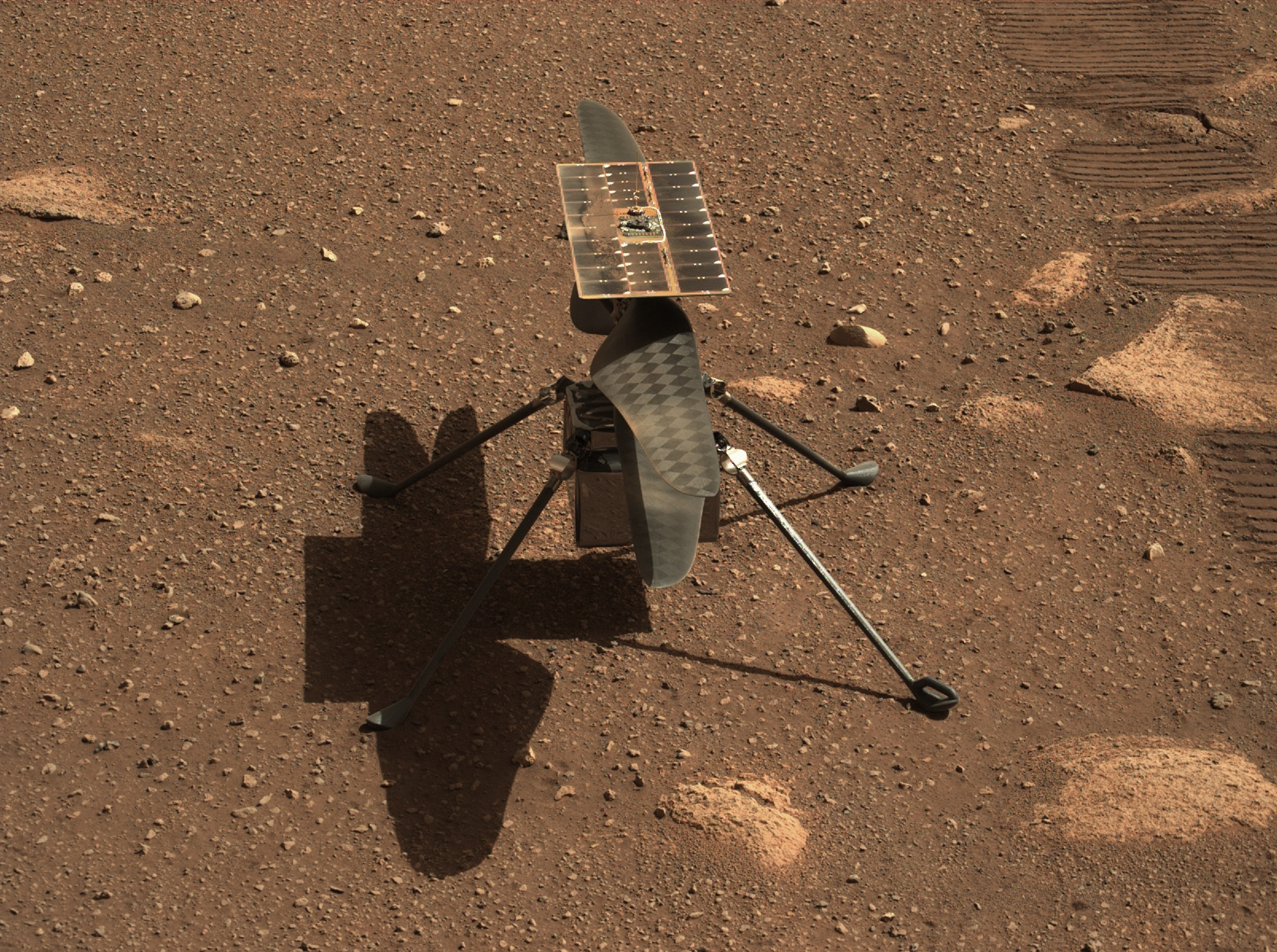

That 4-lb. (1.8 kilograms) chopper, named Ingenuity, landed with the agency's Perseverance rover on Feb. 18 and is gearing up to make the first-ever powered, controlled flights on a world beyond Earth. If all goes according to plan, Ingenuity will get its Wright Brothers moment on Sunday (April 11).

Article continues belowThat first flight will be low and brief; the solar-powered Mars helicopter Ingenuity is expected to get no higher than 10 feet (3 meters) above the floor of Mars' Jezero Crater and stay aloft for 40 seconds or so, mission team members have said. But even pulling off such a modest hop would be an achievement, given that the Martian atmosphere is just 1% as thick as that of Earth at sea level.

Related: How to watch the Mars helicopter Ingenuity's first flight online

Join our forums here to discuss the Perseverance rover on Mars. What do you hope finds?

Rotorcraft generate lift by pushing air. And on Mars, "there are less molecules, basically, to push," Ingenuity project manager MiMi Aung, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California, said during a news conference on Friday (April 9).

That disadvantage outweighs the benefits aircraft receive from Mars' weaker gravitational pull, which is 38% as strong as the tug we feel on Earth's surface. So Ingenuity must do things a bit differently than its terrestrial counterparts.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

For example, the Mars chopper's custom-made, carbon-fiber blades are exceptionally large compared to its 19-inch-tall (48 centimeters) body. The blades are arranged into two rotors, each of which stretches 4 feet (1.2 m) from tip to tip.

And those rotors will spin at about 2,500 revolutions per minute (RPM) to get Ingenuity off the ground — far faster than would be required for a 4-lb. helicopter here on Earth, Aung said. (For perspective: The rotors of light passenger helicopters spin at about 450 RPM during normal flight.)

Mars imposes other challenges as well, such as bone-chilling cold. Perseverance has measured nighttime temperatures as low as minus 117.4 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 83 degrees Celsius) on Jezero's floor, so Ingenuity has a heater to keep itself from freezing.

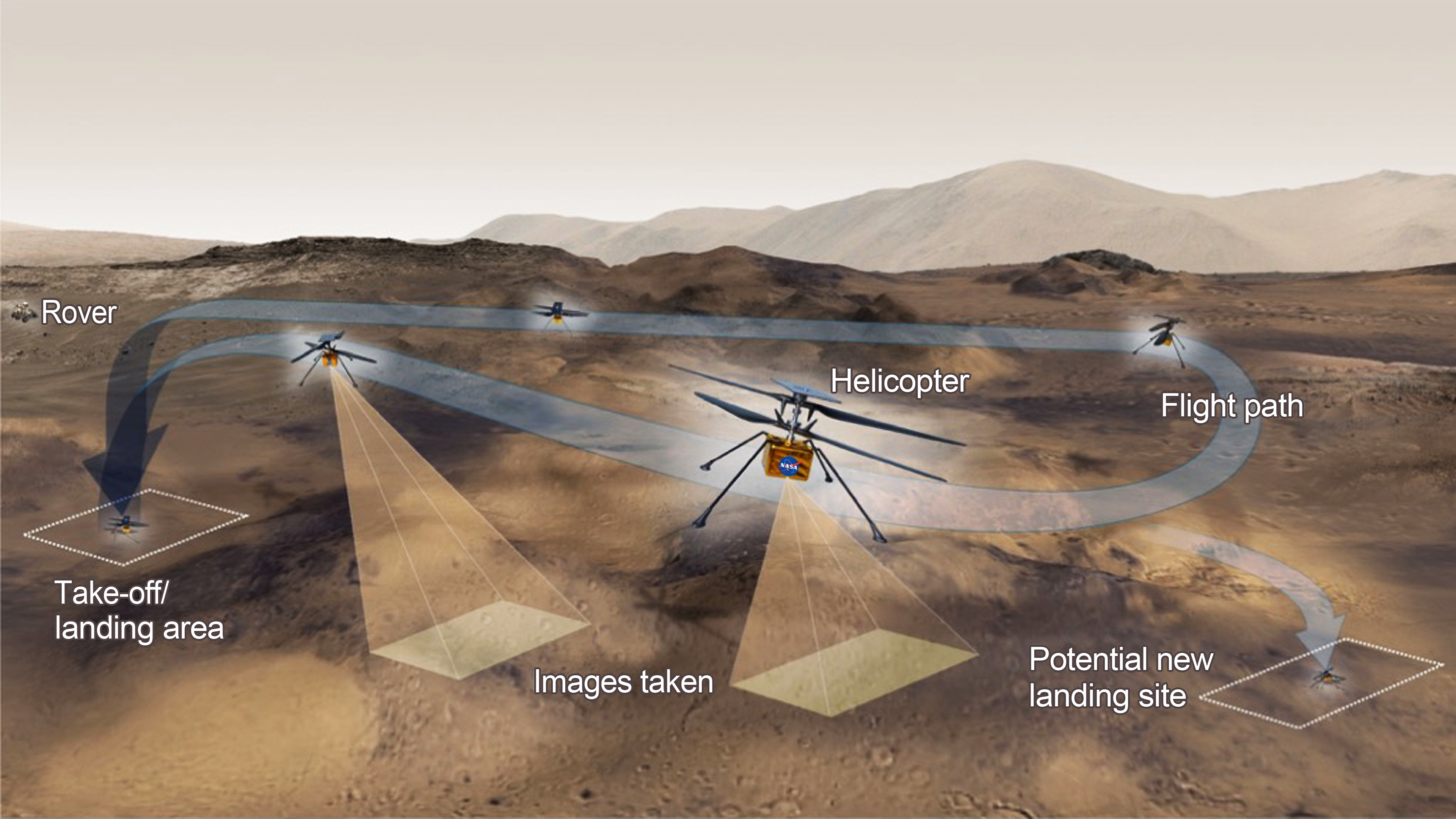

And then there's the distance and isolation. It currently takes more than 15 minutes for a command beamed from mission control here on Earth to reach Mars. Operating Ingenuity in real time with a joystick is therefore not an option; flight commands must be sent in advance.

That's not to suggest that Ingenuity is mindless, however; the little rotorcraft can do a lot on its own. For example, it will get its bearings during flight by analyzing photos snapped by its downward-facing navigation camera.

Those images will be black-and-white, but Ingenuity also sports a 13-megapixel color imager, whose shots should be very crowd-pleasing once they come down to Earth.

The cameras, power system, avionics, communications equipment to relay data to Perseverance — there's a lot of complex gear packed into Ingenuity's small body, even though the chopper doesn't carry any scientific instruments. (It's a technology demonstrator designed to show that powered flight on Mars is feasible.)

There's so much gear, in fact, that a Mars helicopter mission like this wasn't possible until recently, when electronics became sufficiently miniaturized.

"All of it together, to be that light — we just couldn't do it 15 or 20 years ago," Aung said.

She and her team tested Ingenuity extensively here on Earth before launch, flying the copter in a special chamber at JPL that mimicked Red Planet conditions. And Ingenuity has been doing well on Jezero's floor since deploying from Perseverance's belly last weekend; the helicopter's solar array is generating enough power for flight, and initial rotor-spin tests have gone as planned, Aung said.

So there's reason to be optimistic about Sunday's landmark sortie. If that does indeed go well, Ingenuity will fly again — up to five times over a month-long span. Ingenuity will go higher and farther on flights two and three, getting up to 16.5 feet (5 m) off the ground and traveling up to 165 feet (50 m) downrange, Aung said. Success on those missions would pave the way for a "really adventurous" final two flights, she added.

Ingenuity won't fly beyond its month-long window. Perseverance needs to start focusing on its own mission, which involves hunting for signs of ancient Mars life and collecting and caching samples for future return to Earth. The little chopper can't communicate with Earth without the help of Perseverance, so it will be grounded when the car-sized rover moves on.

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.