'Great conjunction' of Jupiter and Saturn will form a 'Christmas Star' on the winter solstice

Jupiter and Saturn will have their closest encounter in almost 400 years on the solstice (Dec. 21).

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

On the last solstice of 2020 (Dec. 21), Jupiter and Saturn will appear the closest together in the night sky in 4 centuries.

Some parts of Earth's Northern Hemisphere have been feeling chilly weather for weeks now, but the official beginning of winter occurs on the solstice. This is the point when the daytime is at its shortest in one hemisphere and when daytime is the longest in the other hemisphere. Dec. 21 is the summer solstice for the southern half of planet Earth.

This year, the solstice happens to converge with a "great conjunction" that some have christened as an early "Christmas star" because of its occurrence hear the holiday.

Video: 'Great conjunction' of Jupiter and Saturn is closest since 1623

Related: Get ready for the 'Great Conjunction' of Jupiter and Saturn

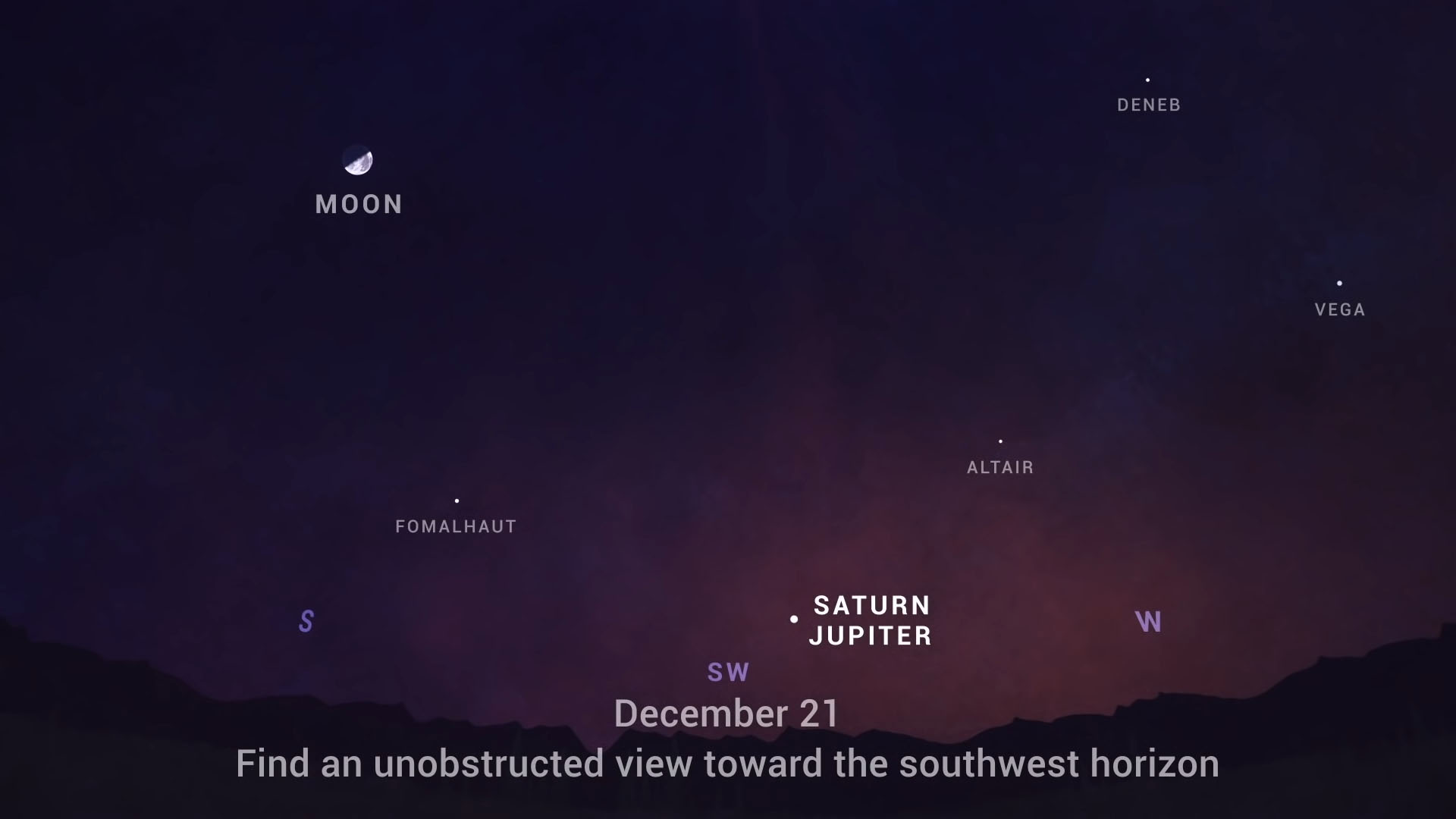

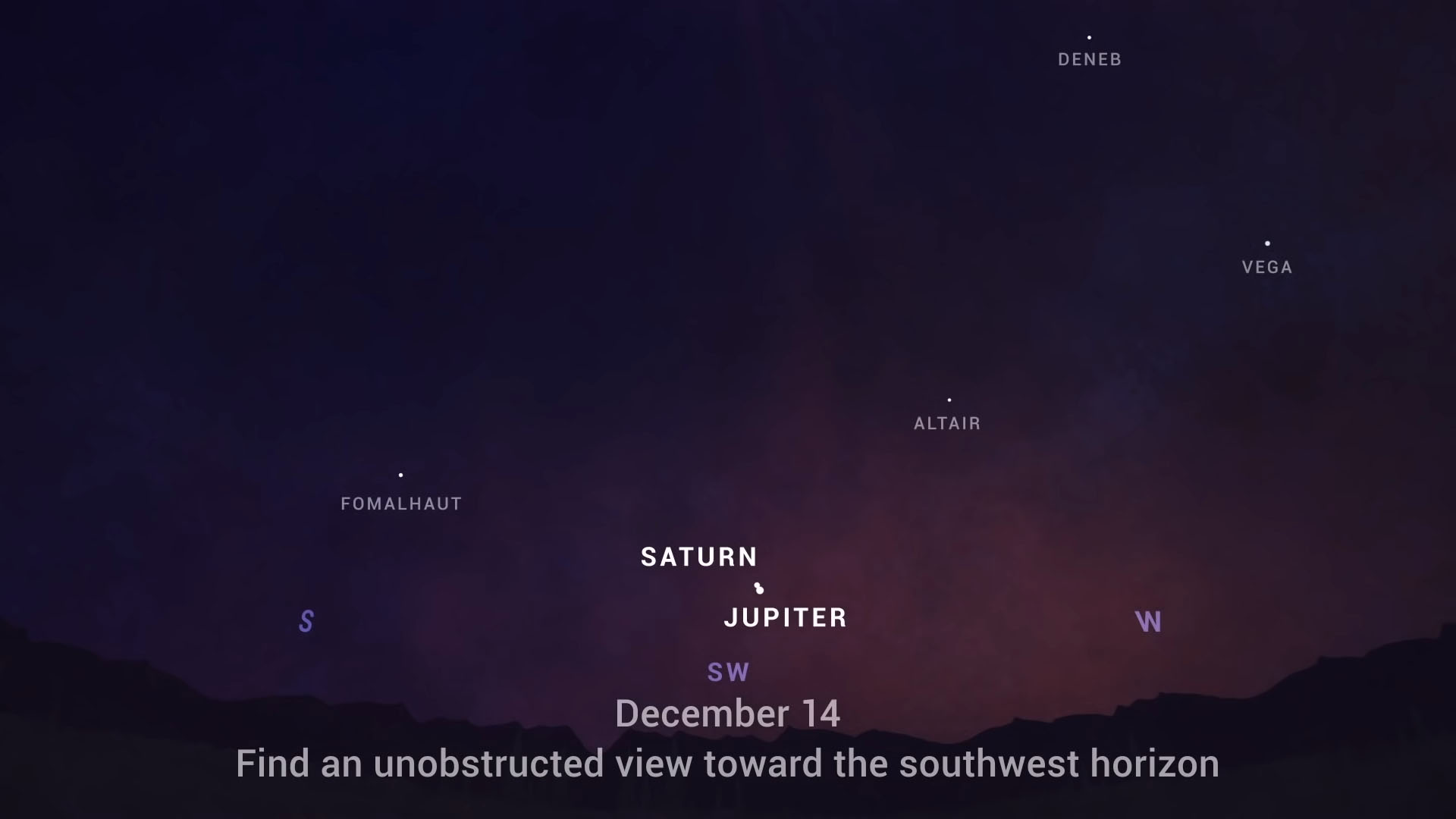

A conjunction happens when planets appear incredibly close to one another in the sky because they line up with Earth in their respective orbits. Over the first three weeks of December, Saturn and Jupiter can be seen near the southwest horizon in the hour after sunset slowly getting closer with each passing night, according to a NASA skywatching statement about this month's nocturnal highlights.

When these two planets converge on Dec. 21 they will be the closest they've been to one another in the night sky since 1623, according to Joe Rao, instructor at the Hayden Planetarium in New York. But that conjunction wasn't visible to skywatchers on much of the Earth because of its location in the night sky. The last time the event was visible from most of the Earth was in 1226, according to Virginia Tech astronomer Nahum Arav.

"This rare event is special because of how bright the planets will be and how close they get to each other in the sky," Arav said in a statement.

The meeting of Jupiter and Saturn in the night sky is referred to as a "great conjunction" because it happens less often than the conjunctions of other planets. Jupiter and Saturn share almost the same celestial coordinates about once every 20 years.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"This means, under high magnification in your telescope you'll be able to see both planets — Saturn with its famous ring system and Jupiter with its cloud bands and Galilean satellites — simultaneously in the same field of view!" according to Rao.

On Dec. 21, Saturn and Jupiter will be about the "thickness of dime held at arm's length" apart in the sky, according to the NASA statement. This alignment is the "greatest" great conjunction between Jupiter and Saturn until the year 2080, NASA officials added.

It's possible that their meeting on Dec. 21 might produce a "winter star" as their lights coalesce and appear like a single point of reflected light with the naked eye.

Follow Doris Elin Urrutia on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.