How the gamma-ray burst of the century surprised spacecraft operators

Europe's galaxy mapper Gaia sent a strange signal that ground controllers first couldn't explain.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

A fleet of space telescopes unexpectedly detected the record-breaking gamma-ray burst GRB221009A onOct.9, sparking concern among spacecraft operators about the blast's odd signal.

The European Space Agency's (ESA) Gaia galaxy mapper sent a strange reading to its controllers on early afternoon, Oct. 9, showing a surprising amount of high-energy particles hitting the spacecraft's detectors. The engineers were puzzled for a while, ESA said in a statement, but eventually realized that the spacecraft, built to measure precise positions of stars in our galaxy, detected the powerful gamma-ray burst GRB221009A which flashed at Earth from a distant world over 2 billion light-years away.

Other ESA spacecraft picked up the signal, described as the most energetic gamma-ray burst ever detected, among them the sun-exploring Solar Orbiter and Mercury-bound BepiColombo. The data, ESA said in the statement, is still being analyzed.

Related: Astronomers just spotted the most powerful flash of light ever seen

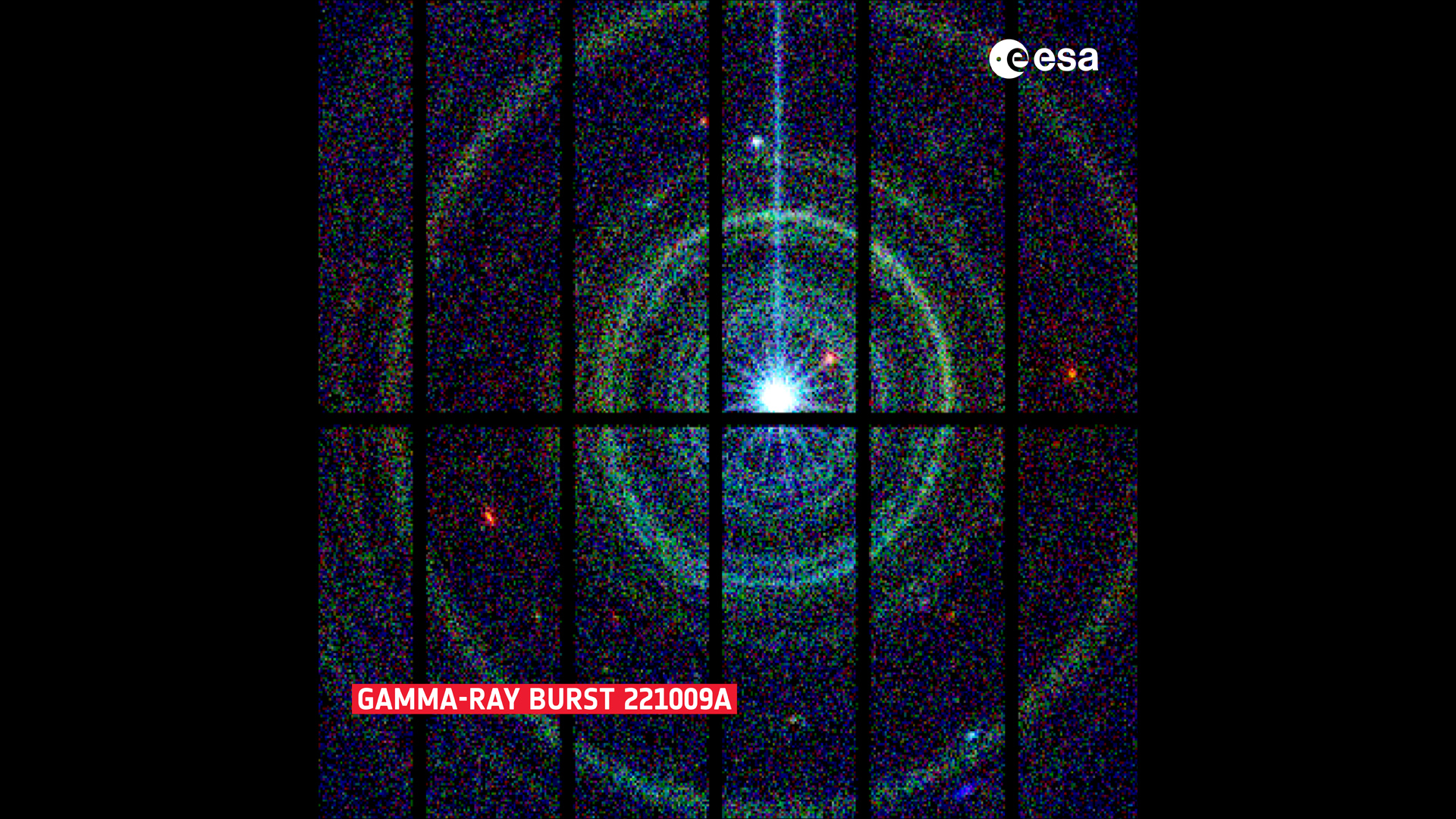

ESA's probably best catch is an image of the gamma-ray burst's immediate aftermath taken by the agency's veteran spacecraft XMM-Newton, which, just like NASA's Swift observatory that spotted GRB221009A first, specializes in detecting high-energy X-ray radiation.

XMM-Newton, in orbit since 1999, captured the mesmerizing rings around the source of the burst that are a result of the interaction between the energetic rays and the dust in our galaxy.

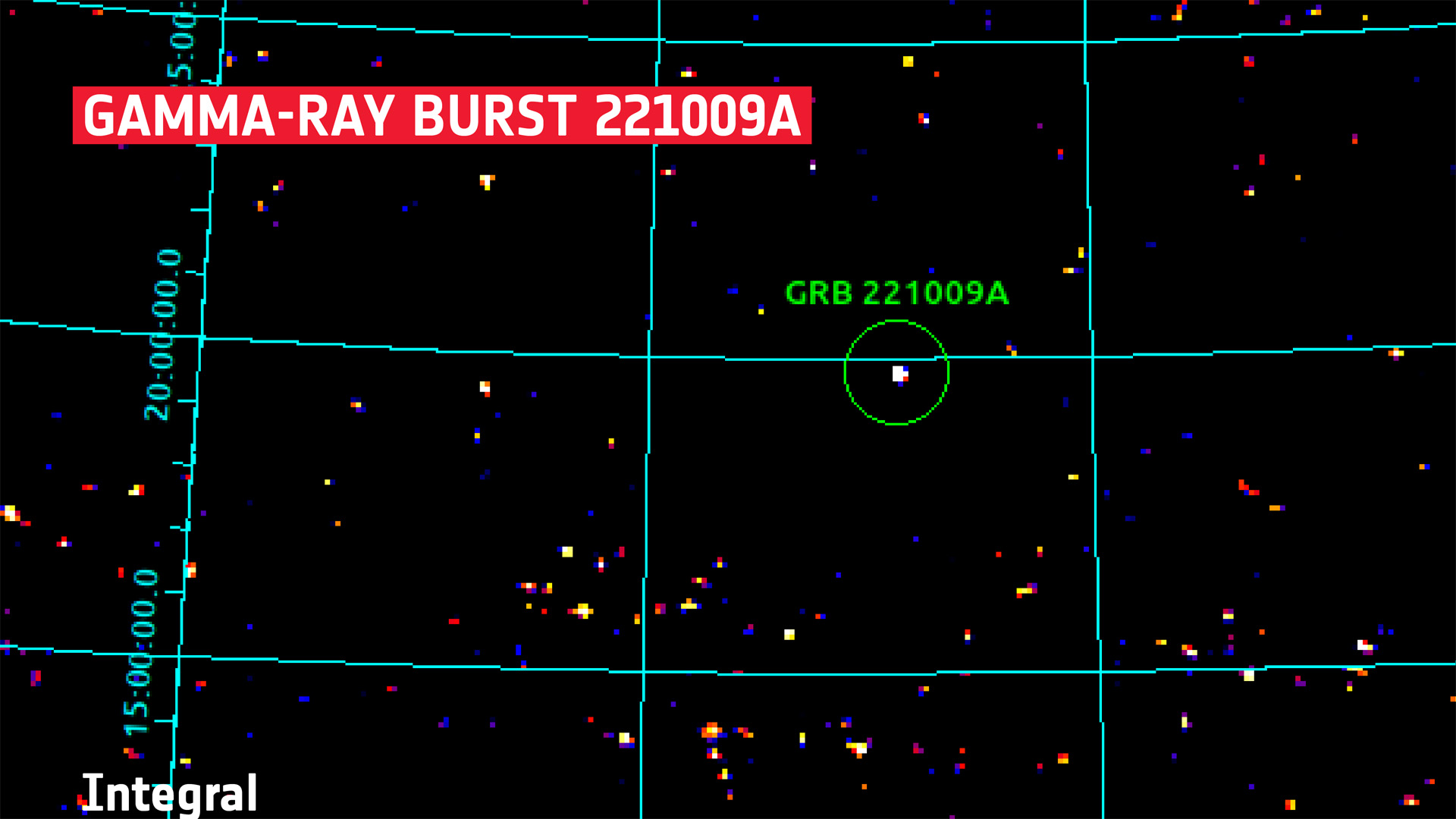

ESA's gamma-ray observatory Integral, which celebrated 20 years in orbit earlier this month, imaged the waning source one day after the explosion, clearly detecting a still active region.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Data gathered by the satellites will help astronomers to learn all there is about this event, which has since been described as a "once-in-a-century" by astronomers.

Gamma-ray bursts are the most energetic explosions known to occur in the universe apart from the Big Bang. Astronomers believe that these bursts mark the birth of black holes in supernova explosions of extremely massive stars. As a vast amount of material from the old collapsing star falls into the new-born black hole, the black hole gets rid of some of it in the form of a powerful jet that bursts into the surrounding space at nearly the speed of light. The jet is rather narrow and therefore the burst can be detected only in the parts of the universe where it aims.

Satellites around Earth detect about one gamma-ray burst per day but only in about 30% cases can astronomers locate the burst's source. GRB221009A, however, was like none seen before, the energy of its photons temporarily blinding the sensitive gamma-ray detectors on specialist satellites.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.