The Scientists Behind the First Black Hole Photo Get Nod from Congress

Shep Doeleman, Katie Bouman and other scientists talked black holes with Congress.

Congress can sometimes feel as distant and impenetrable as a black hole — which was the topic of a House Science Committee hearing held yesterday (May 16).

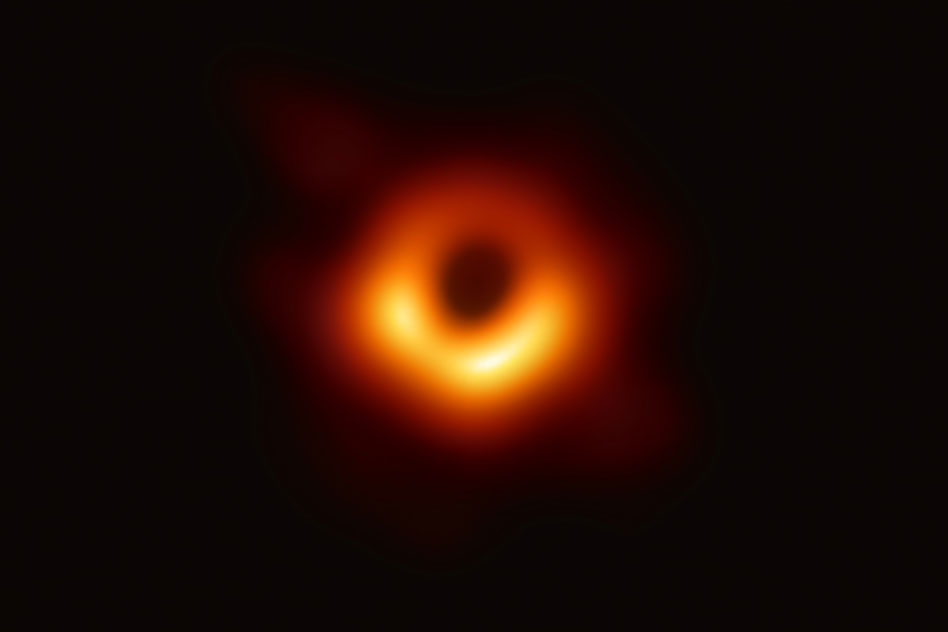

Four scientists affiliated with the Event Horizon Telescope project, which released the first-ever image of a black hole earlier this year, testified at the hearing about how the image was created, the importance of science research and education, and the future of the project itself. Throughout the hearing, the scientists' enthusiasm for black holes and the new image was clear.

"Seeing these images for the first time was truly amazing, and one of my life's happiest memories," Katie Bouman, a computer scientist at MIT whose photograph went viral in the days after the image's release, said during the committee hearing.

Related: Eureka! Scientists Photograph a Black Hole for the 1st Time

The panel also included Shep Doeleman, an astrophysicist at Harvard University and director of the Event Horizon Telescope project; France Córdova, director of the National Science Foundation, which funded the project; and Colin Lonsdale, director of MIT's Haystack Observatory. During the hearing, each panelist shared experiences that got them hooked on science — and touched on how their new contribution could fuel the same process for future generations.

"I think that this picture has really captured the imaginations of a generation of new young scientists," Bouman said. "I think that getting that interest in science to students at a young age will help them enter the STEM [science, technology, engineering and mathematics] fields and make contributions to many different projects."

Throughout her testimony, Bouman focused on emphasizing the importance of collaborating across experience levels and disciplines to succeed at this sort of large, complicated project. "Early-career scientists have been a driving force behind every aspect of the EHT," Bouman said, referring to the Event Horizon Telescope. "No one algorithm or person made this image; it required the talent of a global team of scientists and years of hard work to develop not only imaging techniques, but also cutting-edge instrumentation, data processing and theoretical simulations."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The testimony also offered insight into why the image's release was such a dramatic moment — the team was able to keep the details of the announcement, particularly which black hole had been imaged, under wraps until the coordinated news conferences.

"[Being] bound by a common science vision, it really helps when you want to prevent a leak," Doeleman said. "We had 200 people from around the globe and nobody broke the code, nobody broke the silence, and I think it's because we all understood the impact that it would have. We wanted to be able to tell our story, the scientific story, after peer-reviewed publication of our results, so that's a key part of it."

But of course, the Event Horizon Telescope team doesn't intend to stop its work any time soon, and the representatives wanted to know what would come next.

Related: The Best Space Photos Ever: Astronauts & Scientists Weigh in

"I learned a valuable lesson I hope not to repeat last week, which is that if you miss an episode of 'Game of Thrones,' you find out a couple days later that apparently it all ends with dragons," Sean Casten, D-Ill., said during one of the lighter moments of the hearing. "I don't want to do that again, so can you give us a little hint — you mentioned that you're going to be able to now tune this on the black hole at the center of the Milky Way, when should we be tuning in for that?"

(Doeleman demurred to offer any details, but said he expected the next release within a year.)

But perhaps the most powerful moment of the hearing came toward the end, when Haley Stevens, D-Mich., asked the team to offer a bit of poetic advice about how not to get lost in a black hole, and Doeleman rose to the challenge.

"In 1655, there was an image that startled people: It was the first drawing of a flea, by [Robert] Hooke," he said. "The microscopic world became real for us. All of a sudden something that was invisible to us became real, and it changed the way we thought about our lives."

More than 200 years later, another iconic image was born, Doeleman continued, then another and another. "Think also about the first X-ray, made by Röntgen, of his wife's hand — you could see the ring with the bony structure underneath. It made something visible for the first time that was invisible prior to that. And then think of the Earthrise over the moon, the first 'Blue Marble.' It really put things in perspective for us, it made us feel connected in a way that we hadn't before, it made us feel vulnerable.

"These are iconic images; they're terrifying, but we can't look away," Doeleman said, adding that he believes the new black hole image may join this group of pivotal scientific images.

"It may be the first image we have of a one-way door out of our universe," he said. "It's something that we've been taught it's a real monster exists, that the invisible has become visible, and that maybe it's the beginning of something new, not just the end."

- Images: Black Holes of the Universe

- The 100 Best Space Photos of 2018!

- Earth Day 2019: These Amazing NASA Images Show Earth from Above

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.