5,200 tons of space dust falls on Earth each year, study finds

This makes cosmic dust the most abundant source of extraterrestrial material on Earth.

Every year 5,200 tons (4,700 metric tons) of interplanetary dust particles reach the Earth's surface, a new study reports.

These novel findings suggest that cosmic dust is the main source of extraterrestrial material on Earth, far exceeding the input from larger, more visible meteorites, which are considered to bring less than 10 tons (nine metric tons) of material to Earth every year.

This information can help scientists understand the role that interplanetary dust played in supplying water and carbonaceous molecules to a young Earth early in our planet's formation history.

Related: Fiery 'airburst' of superheated gas slammed into Antarctica 430,000 years ago

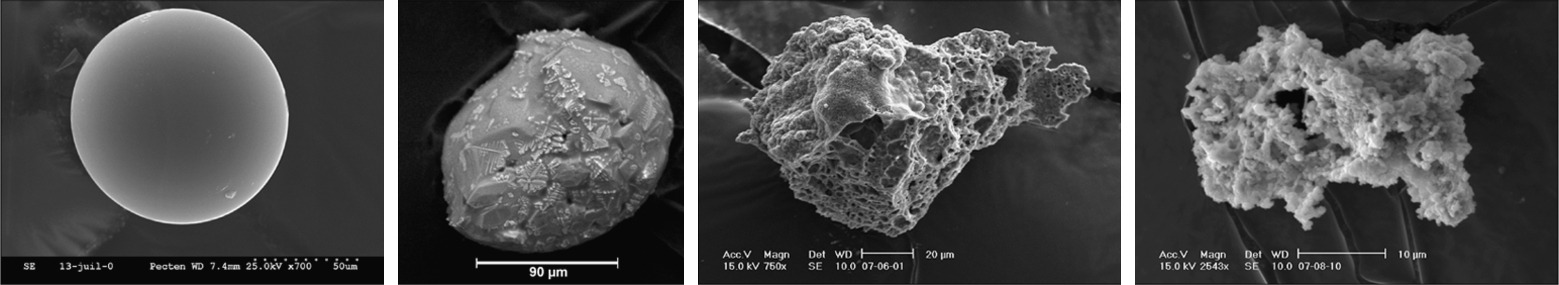

Hunting for interplanetary dust particles is by no means an easy task. Firstly, how do you find micrometeorites that measure just a few tenths to a hundredth of a millimeter in size? (A human hair for example is around 70 micrometers in diameter.)

Crucially you need a blank canvas, void of terrestrial dust. For this, researchers look to the heart of Antarctica.

Over the last 20 years, physicist Jean Duprat of the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) has led six research expeditions to the Franco-Italian Concordia station (Dome C), which is located 680 miles (1,100 kilometers) off the coast of Adélie Land, Antarctica.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Dome C offers the perfect hunting ground for cosmic dust due to the low rate of snowfall and pristine snow conditions, CNRS said in a statement.

The team collected pure snow samples from trenches over 6.5 feet (2 meters) deep, located upwind of the research station, to avoid any human contamination of the samples.

Over two decades researchers collected enough micrometeorites (ranging from 30 to 300 micrometers in size) to be able to calculate how much extraterrestrial dust falls to Earth each year.

The scientists estimated that a total of 15,000 tons (13,600 metric tons) of cosmic dust rains down on the Earth annually, though most of the material is lost on entry as it burns up in Earth's atmosphere. This leaves 5,200 tons (4,700 metric tons) of interplanetary dust to settle on the surface of our planet each year.

The culprit for a majority (around 80%) of this interplanetary dust is the Jupiter family comets. These cosmic snowballs of frozen gases, rock and dust primarily originate in the Kuiper Belt, just beyond the orbit of Neptune.

Whilst the rest of the space dust is thought to come from asteroids; the small rocky bodies leftover from the formation of our solar system.

The findings are a result of collaboration of scientists from the CNRS, the Paris-Saclay University and the National museum of natural history with the support of the French polar institute.

The research was published on April 15 in the journal Earth & Planetary Science Letters.

You can follow Daisy Dobrijevic on Twitter at @DaisyDobrijevic. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Daisy Dobrijevic joined Space.com in February 2022 having previously worked for our sister publication All About Space magazine as a staff writer. Before joining us, Daisy completed an editorial internship with the BBC Sky at Night Magazine and worked at the National Space Centre in Leicester, U.K., where she enjoyed communicating space science to the public. In 2021, Daisy completed a PhD in plant physiology and also holds a Master's in Environmental Science, she is currently based in Nottingham, U.K. Daisy is passionate about all things space, with a penchant for solar activity and space weather. She has a strong interest in astrotourism and loves nothing more than a good northern lights chase!