Does the moon need its own time zone? We may need to decide soon

Space agencies may need to change how we keep time during long-duration crewed space missions.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

With the next era of lunar exploration on the horizon, scientists have begun to consider how time should be kept on the moon and how lunar missions will fix their own positions independent from Earth.

This rethink culminated in the agreement, at a meeting of space agencies in November 2022, that an internationally accepted common reference time for the moon is vital. A joint international effort is now being launched in an attempt to achieve this.

To date, each new moon mission has operated on its own timescale, which is related to time here on Earth. This strategy requires deep-space antennas used for two-way communication with mission control to also keep onboard chronometers synched to terrestrial time. This way of keeping time on the moon won't be feasible on some future spacecraft, however, such as NASA's moon-orbiting Gateway space station, which will need to coordinate with a wealth of other lunar and space missions.

Related: The 10 greatest images from NASA's Artemis 1 moon mission

Once astronauts are staying at Gateway, the space station will be resupplied via regular NASA Artemis launches. This activity will lead up to the establishment of a crewed base near the lunar south pole, if all goes according to plan.

But even prior to these crewed missions, numerous uncrewed missions — including a multitude of cubesats launched by each Artemis mission and the European Space Agency's (ESA) Argonaut European Large Logistics Lander — will be in place around the moon.

These missions will need to interact and communicate with each other to perform joint observations, and perhaps even to meet up with each other.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

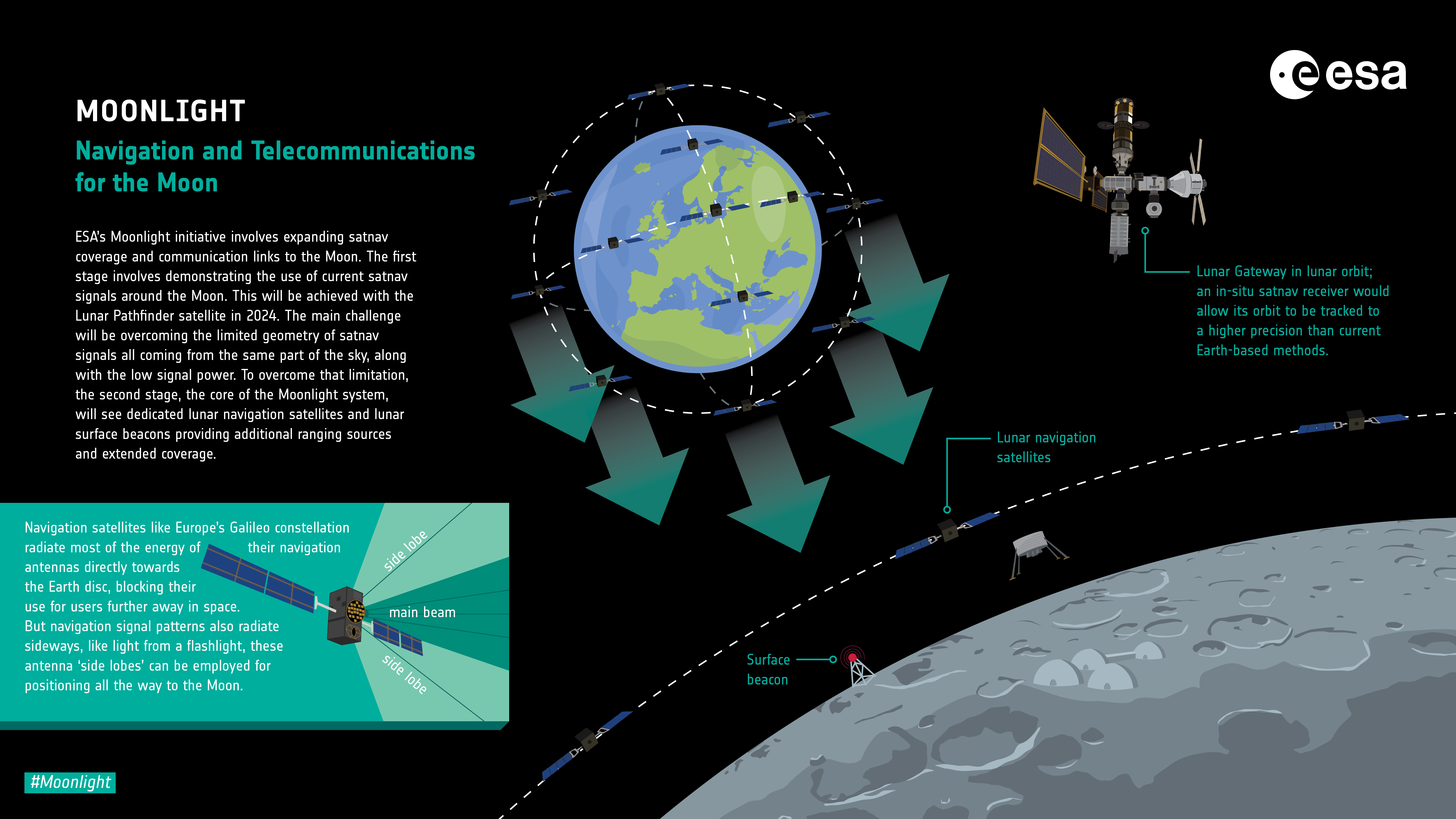

Facilitating these communications will be the ESA's Moonlight lunar communication and navigation service and an equivalent NASA service, the Lunar Communications Relay and Navigation System, linking missions with each other and with Earth. To interact and maximize interoperability, these systems will need to employ the same timescale as the crewed and uncrewed missions they support, experts say.

"This will allow missions to maintain links to and from Earth, and guide them on their way around the moon and on the surface, allowing them to focus on their core tasks," Moonlight system engineer Wael-El Daly said in an ESA statement. "But also, Moonlight will need a shared common timescale in order to get missions linked up and to facilitate position fixes."

Taking guidance from Earth's global navigation system

A similar system linking time with locations in a geodetic reference frame has already been achieved here on Earth; it forms the basis of our Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS). The system is used by an array of technology, including smartphones, to calculate the position of its user to a meter or even a tenth of a meter.

"The experience of this success can be reused for the technical long-term lunar systems to come, even though stable timekeeping on the moon will throw up its own unique challenges — such as taking into account the fact that time passes at a different rate there due to the moon's specific gravity and velocity effects," ESA's chief Galileo engineer Jörg Hahn said in the same statement.

Accurate navigation requires extremely rigorous timekeeping. For example, terrestrial satellite navigation systems, like Galileo in Europe and GPS in the U.S., have their own distinct timing systems. But these systems possess fixed offsets relative to each other down to a few billionths of a second and are also fixed to the Universal Coordinated Time (UTC) global standard, which is maintained by the Paris-based Bureau International de Poids et Mesures (BIPM). UTC is also used by the internet and aviation, as well as scientific experiments that require highly precise time measurements.

What is currently unsettled is whether one agency will be responsible solely for maintaining the proposed new lunar chronology system, as the BIPM does for UTC. Another undecided element is if "lunar time" will be independent or will be synchronized with time on Earth.

Settling such questions requires overcoming several technical hurdles, such as the fact that clocks run slower on the moon than they do on Earth. Though lunar clocks gain just 56 millionths of a second each Earth day, this difference would eventually lead to problems in precision measurements. Additionally, clocks would also tick at different rates on the lunar surface compared to their rate while in orbit.

Related: Fun information about Earth's moon

"Of course, the agreed time system will also have to be practical for astronauts," Moonlight Management Team member Bernhard Hufenbach said in the statement. "This will be quite a challenge on a planetary surface where in the equatorial region each day is 29.5 days long, including freezing fortnight-long lunar nights, with the whole of Earth just a small blue circle in the dark sky. But having established a working time system for the moon, we can go on to do the same for other planetary destinations."

Additionally, Earth-based GNSS also depends on the International Terrestrial Reference Frame (ITRS) a three-dimensional coordinate system for Earth established in 1991. This allows consistent measurement of precise distances between points across our planet. Moon navigation will require a similar, internationally accepted moon-centered — or "selenocentric" — coordinate reference frame.

"Throughout human history, exploration has actually been a key driver of improved timekeeping and geodetic reference models," said ESA Moonlight Navigation Manager Javier Ventura-Traveset.

"It is certainly an exciting time to do that now for the moon, working towards defining an internationally agreed timescale and a common selenocentric reference, which will not only ensure interoperability between the different lunar navigation systems but which will also foster a large number of research opportunities and applications in cislunar space," Ventura-Traveset added.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, or on Facebook and Instagram.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.