Yes, Saturn's Rings Are Awesome — NASA's Cassini Showed Us Just HOW Awesome.

When the solar system decided it liked Saturn and wanted to put a ring on it, it put together the most stunning, complex puzzle ring possible, so it's no surprise scientists are still piecing together how it works.

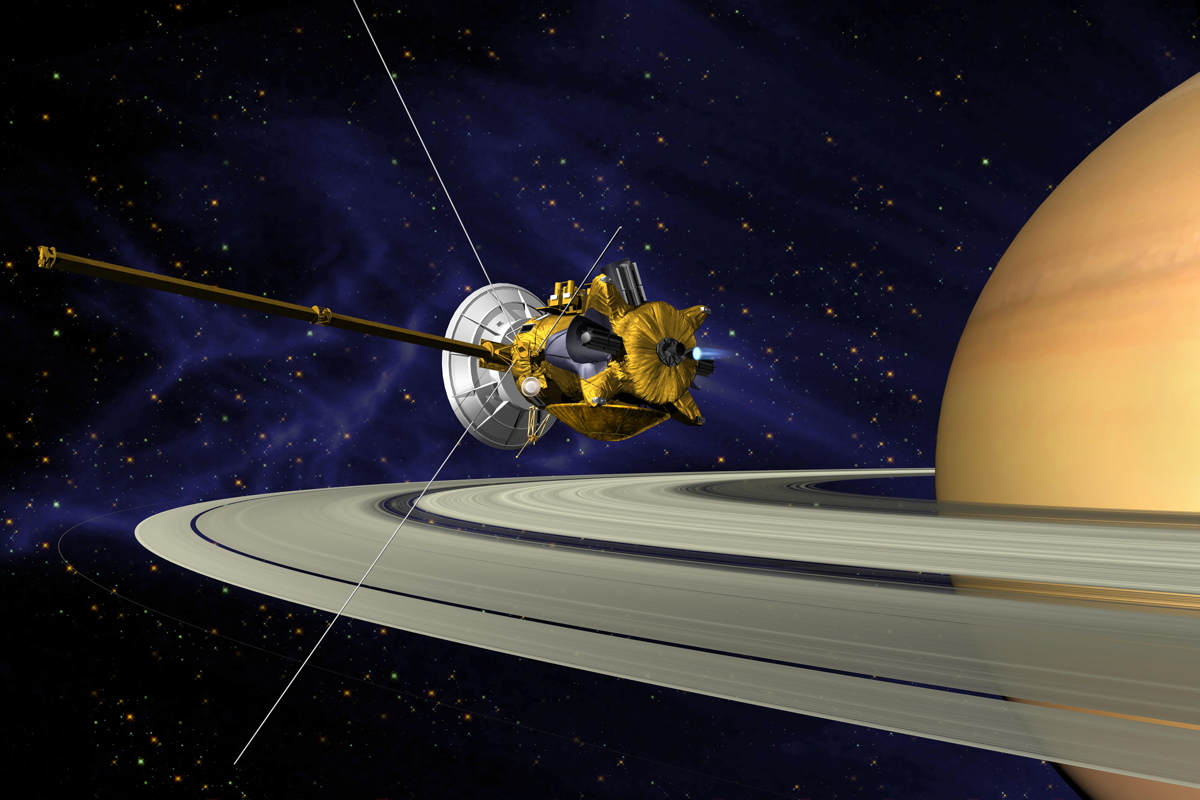

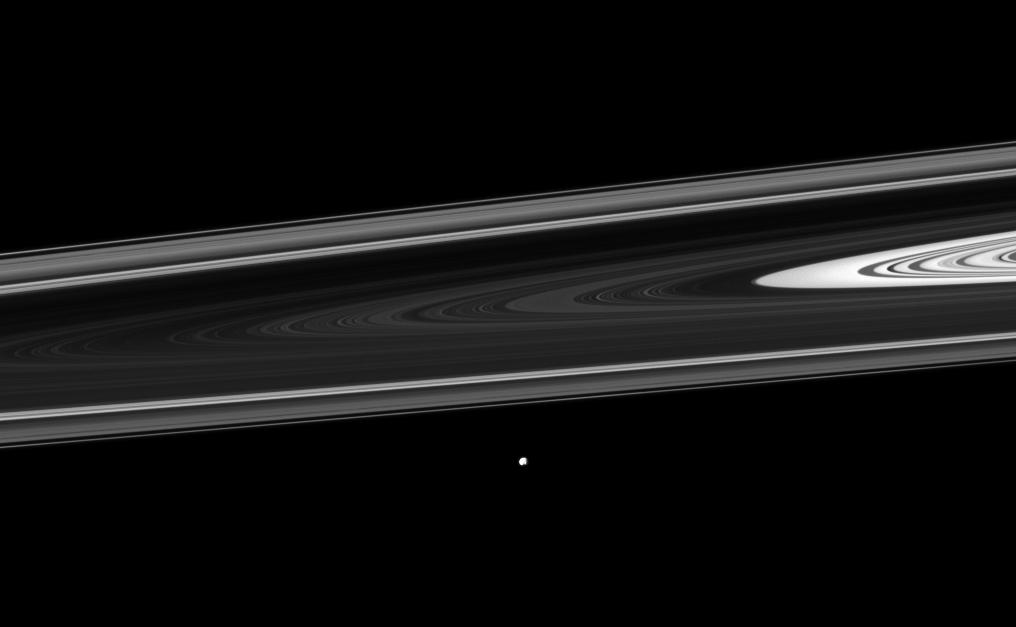

For centuries, Saturn's rings seemed simple, if beautiful — until NASA's Cassini spacecraft arrived at the planet in 2004 and began to reveal their complexity. Now, nearly two years after the end of the mission, researchers are still publishing new studies trying to better understand the features based on the data the spacecraft gathered.

"Getting closer to the rings, getting higher resolution images and spectra, we're starting to get new views, some of the best-ever views of some of the dynamics and evolution of what's going on in Saturn's rings," Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, told Space.com.

Related: Photos: Saturn's Glorious Rings Up Close

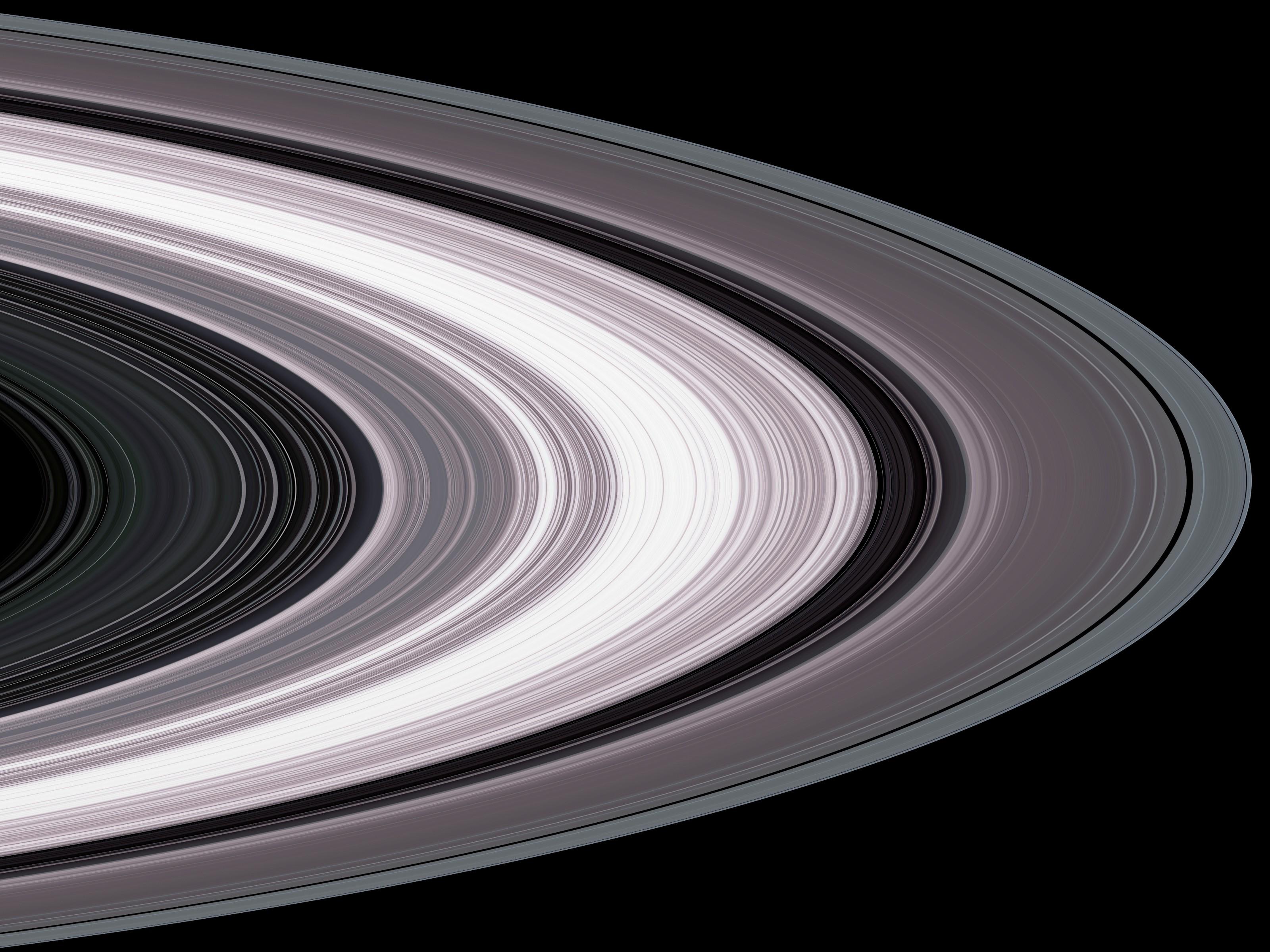

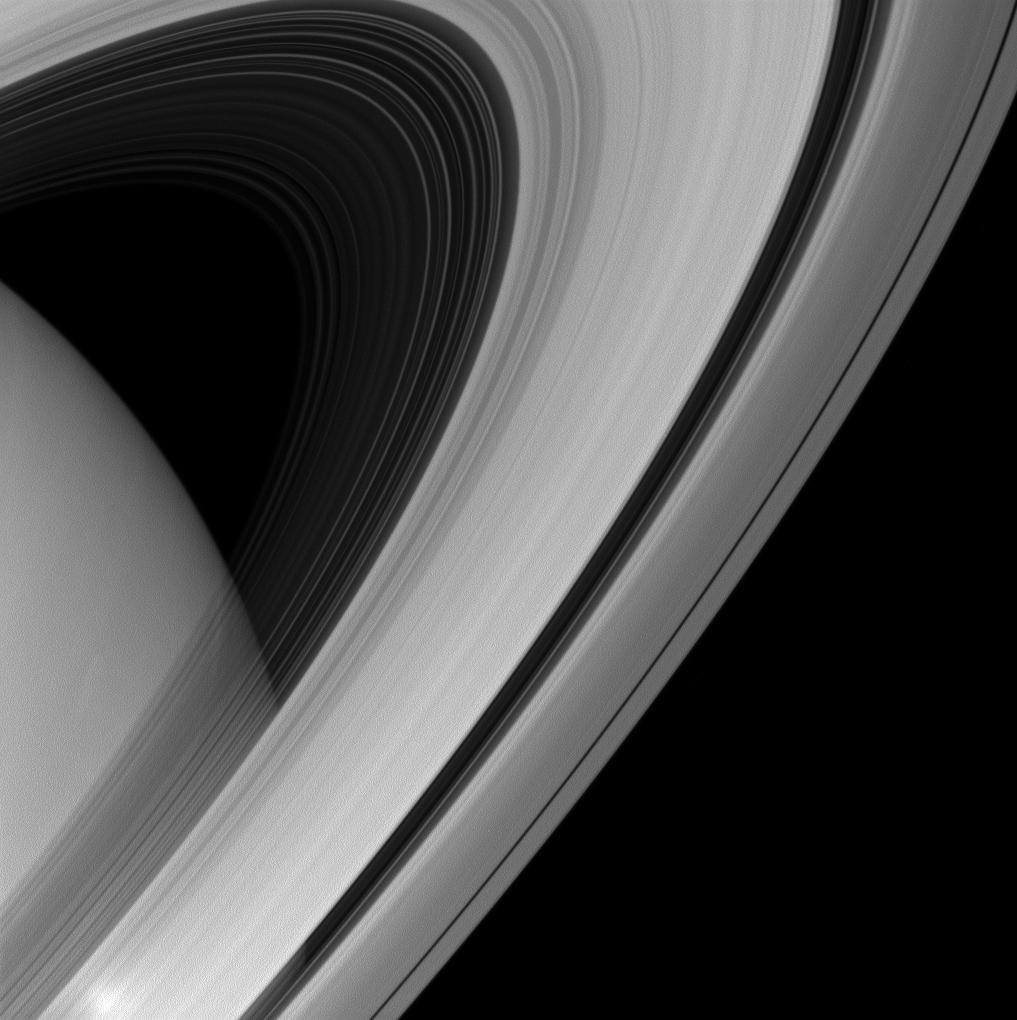

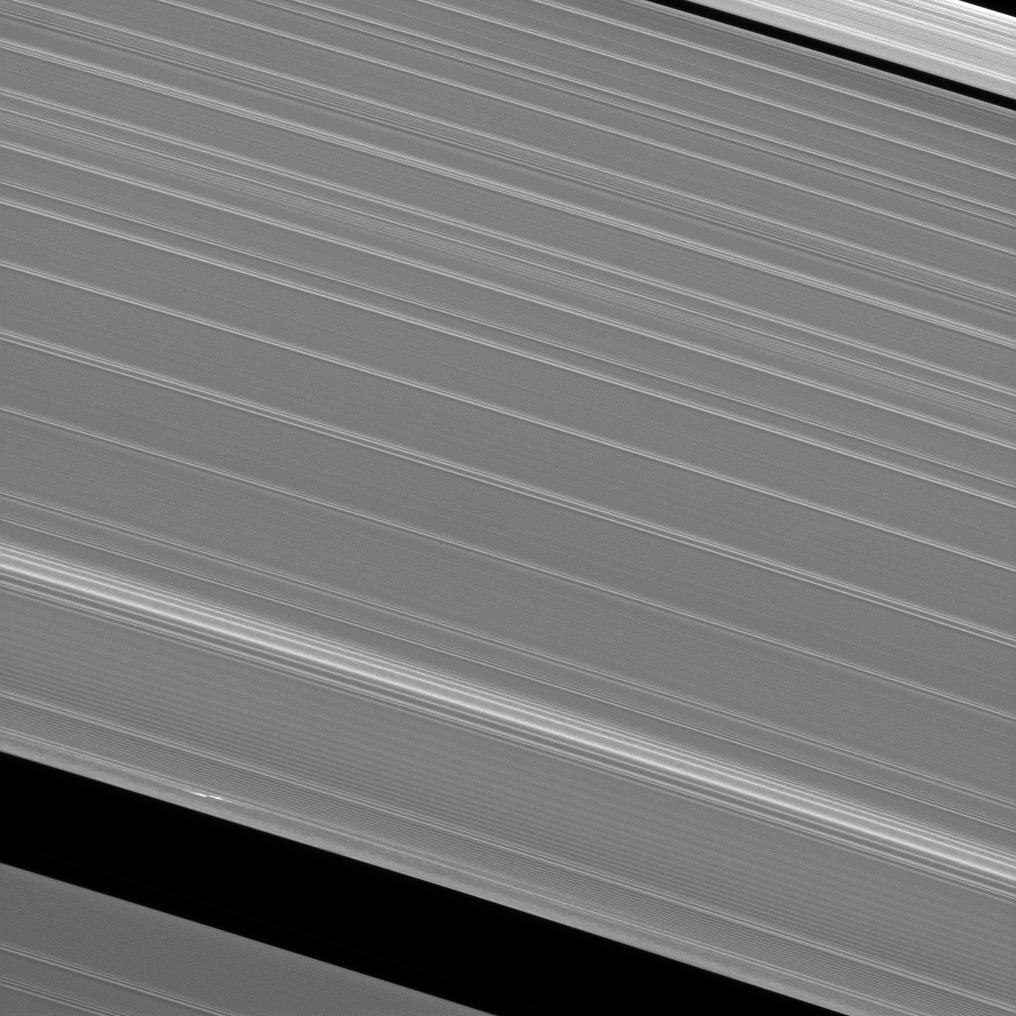

Spilker is a co-author on a new paper that describes in detail some of the strange features Cassini studied within Saturn's rings. "What's fascinating is as we got ever closer, we just saw more and more structure in the rings," she said. What seemed from afar to be flat, boring sheets turned out to be vibrant grooved structures embellished with small features and gaps.

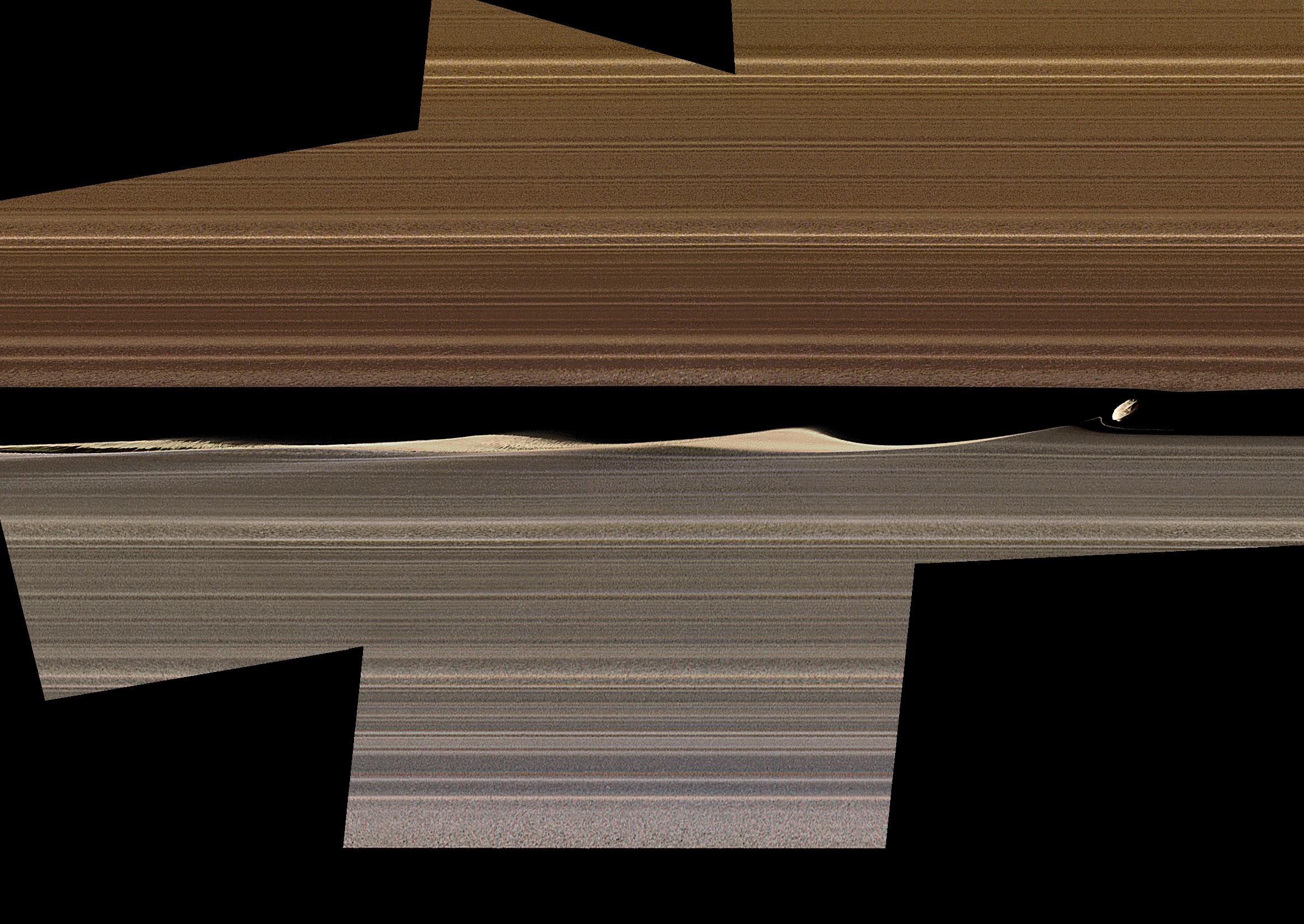

Some of the detail is clear evidence of change, like a series of bumps caused by the interaction between the rings and the small moon Daphnis.

And scientists are still figuring out what causes those details. "A lot of the structure, we don't understand what maintains it over the long term," Spilker said. "We know the ring particles stick together at least for a short period of time … maybe some of the largest particles even create spaces around them."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The new paper describes some of the structures that seem to be created this way, which scientists have nicknamed propellers for their jagged blade-like shape that pops against the smooth striations of the rings. Other features are more subtle: small changes in the rings' structure or composition that make patches appear streaky or clumpy.

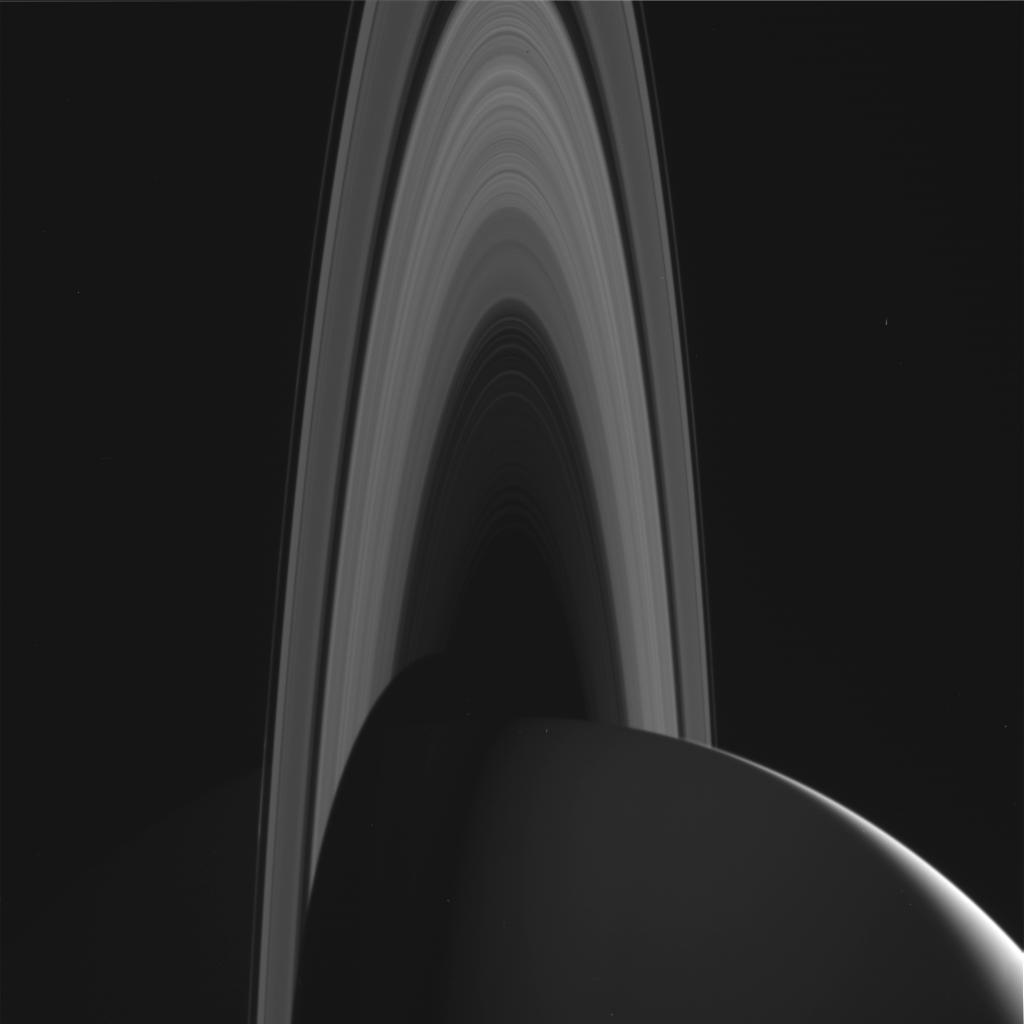

Someday, Spilker hopes, scientists could return to inspect the rings still more closely. As they designed Cassini's path over its 13 years at Saturn, the mission's engineers worried that particles from the rings could damage the spacecraft, so even during its last, most dangerous maneuvers through a gap between the rings, they were careful to keep the spacecraft protected, sheltering behind its high-gain antenna.

But as the spacecraft flew, its operators realized those particles were safe — some process that scientists still don't understand ground them up so small they resembled particles of smoke. That realization could pave the way for more daring ring-exploration missions, although larger particles within the rings could still pose a threat.

Cassini stopped gathering data in September 2017, diving into Saturn's atmosphere to burn up. But scientists still have the spacecraft's data, and they know there's still plenty more mysteries to find there. "I think in so many ways we've really just skimmed the cream off the top of the data," Spilker said.

New research and hypotheses based on Cassini data are described in three papers published today (June 13) in the journal Science.

- Cassini's Death Dive into Saturn Reveals Weird Ring 'Rain' & Other Surprises

- Saturn's Moon Titan May Have 'Phantom Lakes' and Caves

- In Photos: Cassini Mission Ends with Epic Dive into Saturn

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.