‘Blue Stragglers’ in Space May Mask True Age of Star Clusters in Hubble Views

By spying on star clusters in a nearby galaxy, the Hubble Space Telescope has shown that star clusters aren't always as old as they appear.

The long-running observatory turned its attention to collections of stars in the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), a satellite dwarf galaxy of the Milky Way located about 160,000 light-years from Earth. (A light-year is the distance light travels in a year, or roughly 6 trillion miles or 10 trillion kilometers).

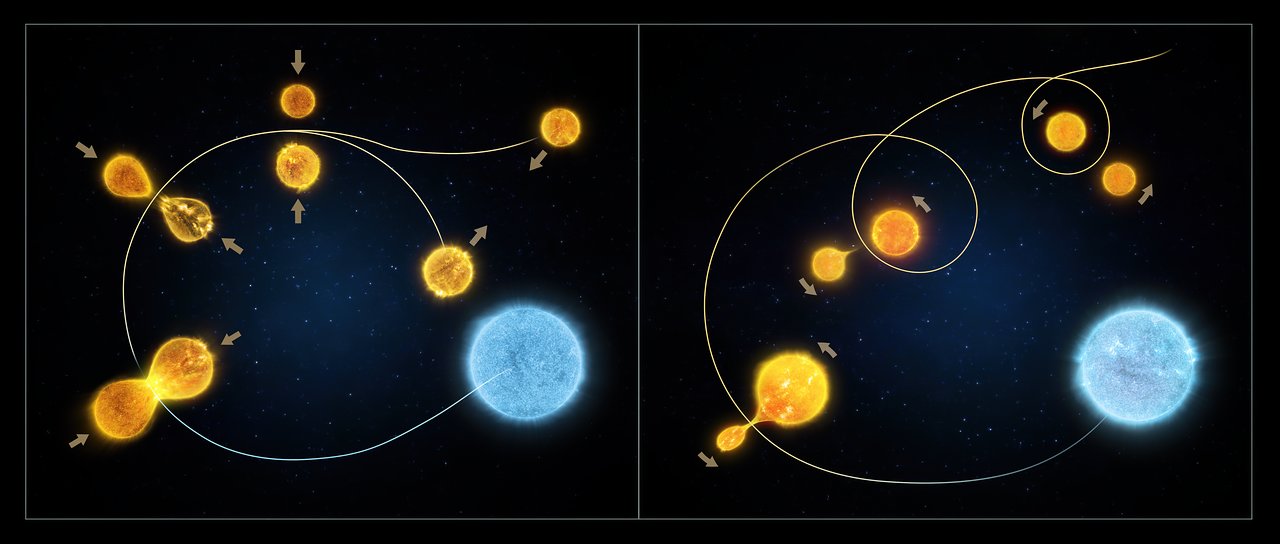

In the LMC, astronomers observed the behavior of bright, blue stars known as "blue stragglers." These stars receive a bunch of extra fuel from other stars in their environment, which makes them bigger and brightens them up. This usually happens when a star steals gas from a neighbor or two stars crash into each other.

Related: How Mysterious Vampire Stars Drain Life from Neighbors

Video: Watch Blue Straggler Stars Move Over Time in Animation

These stragglers revealed something interesting about how star clusters evolve, the researchers said. Because they are so bright, they are easy to track even if they are buried deep within the group of stars. They thus make a handy reference for star movement in a star cluster, which can consist of up to 1 million stars.

The mutual gravitational pull between stars in a cluster tends to change the cluster's structure over time, a process that astronomers call "dynamical evolution." Specifically, heavy stars sink toward the middle of the cluster and low-mass stars flee to the outskirts, Hubble officials said in a statement.

The "stragglers" showed, for the first time, that star clusters can be different physical shapes even if they formed during the same period. That's because the varying pull between stars "causes a progressive contraction of the cluster core over different time scales," Hubble officials said, "and means that star clusters with the same chronological age can vary greatly in appearance and shape because of their different 'dynamical ages.'"

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The research was led by Francesco Ferraro, an astrophysicist at the University of Bologna in Italy. The work was published Sept. 9 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

- Hubble Spots Thousands of 'Orphaned' Star Clusters Between Galaxies

- Dying Star Robbed of Its Stellar Mass by Covert Companion

- Binary Star Systems: Classification and Evolution

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.