Astronomy needs a new long-term approach, new paper argues

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Paul M. Sutter is an astrophysicist at SUNY Stony Brook and the Flatiron Institute, host of "Ask a Spaceman" and "Space Radio," and author of "How to Die in Space." Sutter contributed this article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Next-generation observatories, both on the ground and in space, have truly astronomical costs. Indeed, they are on the same scale as massive civil engineering projects, like new rail lines and upgrades to shipping canals. And if there's no immediate societal benefit to these projects, we may be less inclined to continue financing them.

If scientists want astronomy to thrive throughout the 21st century, we need a new approach, one astronomer proposes in a new paper: to view new observatories through a lens of public benefit, wrapping them up in other, space-based infrastructure endeavors.

Article continues belowRelated: Space telescopes of the future: NASA has 4 ideas for great observatory to fly in 2030s

The frontier of knowledge

The future of astronomy lies in space. Currently, space-based observatories complement ground-based programs. In space, astronomers don't have to deal with atmospheric distortion or the filtering of certain wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum. In the meantime, ground-based astronomy has its own strengths, like the ability to build incredibly large telescopes and much cheaper development cycles.

But in the coming decades, there will be some science goals that can be achieved only in space. Building telescopes larger than 20 meters (65 feet) across is a tremendous logistical and engineering challenge on Earth, but they could be deployed with relative ease in space. These massive observatories could directly image exoplanet surfaces, for example, or peer into the farthest reaches of the cosmos.

As another example, Earth is saturated with radio noise. A radio observatory on the far side of the moon would offer unparalleled access to radio signals arriving from deep space, thus opening up a new frontier in that field.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

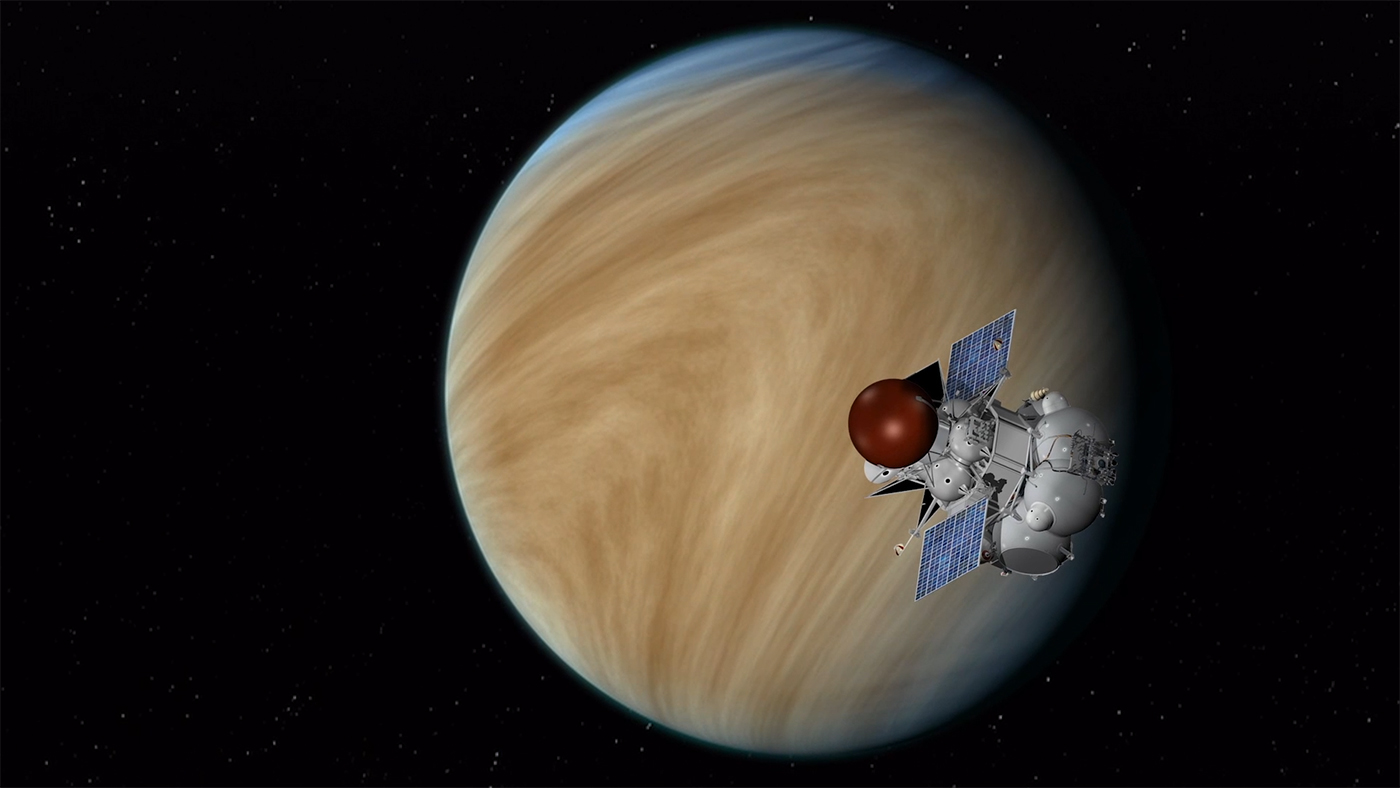

We can take all the pictures we want of other planets, but we need to send probes there if we want to get direct access to the planets' geological records and the clues to the formation of the solar system they contain.

Bounded opportunities

Unfortunately, our current strategy for designing and launching space-based astronomy missions will not be feasible in the long run, according to a paper published recently in the preprint database arXiv.org.

There are two main problems with our current model, according to the paper. For one, the costs of new observatories and missions easily climb into the hundreds of millions, and even billions, of dollars. Those kinds of price tags are usually reserved for major civil projects, which have direct and well-understood benefits to the public. By contrast, the benefits of astronomical projects — while certainly worthy scientific endeavors — are less understood by the public.

Second, the timescales for launching new missions continue to grow. That's because, with these large, expensive missions, we usually get only one shot for the mission to go right, or the whole thing was wasted. To minimize risk, mission leaders have to be extra careful, which causes time delays and cost overruns. It can easily take 10 to 20 years for a mission to go from the planning stage to actual data collection.

These long timescales are putting a heavy burden on young scientists, who may spend their entire careers preparing for a single mission to deliver useful science, and, in turn, may discourage new astronomers from entering the field.

So what can astronomers do about it? How can they ensure public support? How can they live up to the promises made to young astronomers?

A better space

The solution, according to the paper, is to ensure that new space-based astronomy programs have direct public benefit. Astronomers need to be able to sell these observatories to the wider public. And while there are benefits of understanding the history of the solar system or the nature of distant exoplanets, it would be even better if the public saw direct, immediate and financial value in the programs.

First, space agencies and national funding bodies should focus on smaller, more frequent missions, the paper author proposes. For example, astronomy will have a lot to gain from the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope, but we also would have gained a lot from a dozen new Hubble-like telescopes. Smaller, less-expensive programs can also benefit from faster technological development and lowered cost by using proven techniques.

Instead of focusing on large flagship missions, the paper author says, astronomers should aim to weave themselves into the fabric of space industrialization and utilization. Private companies are eager to launch new satellites for telecommunication. So is there a way for astronomy to take advantage of that?

Second, the astronomical community should engage with engineers, architects, energy suppliers and other professionals, according to the paper. By engaging with industry partners, astronomers could find new avenues for funding and continued support.

Is there an opportunity for a new astronomical observatory to provide a direct public benefit? For example, an array of radio antennas on the far side of the moon would help us unlock the origins of stars. What else could we do with that? To build an observing station on the moon, we would have to develop a lot of technologies to locally extract resources from the lunar regolith — technologies that would be of immediate practical benefit to many private and public interests in space.

In this vision, astronomy serves as the vanguard for developing and deploying space-based technology. That technology then enables more infrastructure in space, which then allows for even grander scientific experiments. Indeed, it's entirely possible that this approach — de-emphasizing giant, science-only missions and encouraging smaller, industry-interwoven missions — could make astronomers' dreams come true even faster.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Paul M. Sutter is a cosmologist at Johns Hopkins University, host of Ask a Spaceman, and author of How to Die in Space.