NASA Adds Video Camera To Next Mars Rover

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

NASAhas added a video camera to its next Mars rover to take viewers on Earth alongfor the ride when the six?wheeled robot lands on the Martian surface.

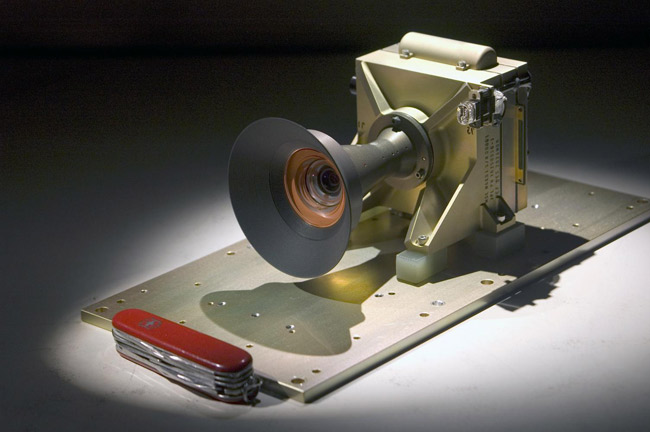

Calledthe Mars Descent Imager, or MARDI, the camera is on the front-left side of the MarsScience Laboratory Curiosity and should record high-resolution videoapproximately two minutes before the rover's planned landing on Mars in August2012. The rover is slated to launch toward Mars next year.

Ifall goes well, the initial video views should show Curiosity's heat shieldfalling away from beneath the rover, revealing a swath of Martian terrainbelow, illuminated in afternoon sunlight, rover officials said. The firstscenes would cover ground a few miles across. Subsequent images will close inand cover a smaller area each second.

Viewersshould, however, prepare for a bumpy ride.

Thefull-color video will likely spin and shake as Curiosity's parachute - andlater its rocket-powered backpack - work to slow the rover's descent, accordingto a NASA description. The left-front wheel should then come into the field ofview when Curiosity extends its mobility and landing gear, after which Curiosity's surface mission can begin.

Thelanding will be recorded at approximately four frames per second and at aresolution of about ?1,600 by 1,200 pixels per frame. The footage will besafely stored in the Mars Descent Imager's own flash memory during the landing.

Arelay of information

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Curiosity,which will be about 150 million miles (250 million km) from Earth on landingday, is expected to beam images and other data back to Earth via relay by oneor two Mars orbiters. The daily data volume will also be limited by the amountof time the orbiters spend overhead each day.

"Wewill get it down in stages," said Michael Malin of Malin Space ScienceSystems, the San Diego, Calif.-based company that built the Mars Descent Imager."First we'll have thumbnails of the descent images, with only a few framesat full scale."

Subsequentdownlinks of the data will deliver additional frames, which will be selectedbased on what the thumbnail versions display.

"Thelower-resolution version from the thumbnail images will be comparable in imagequality to a YouTube video," Malin said. "The high-definitionversion, however, will not be available until the full set of images can betransmitted to Earth, which could take weeks, or even months, as it sharespriority with data from other instruments."

Aglimpse at the surroundings

TheMars Descent Imager will also provide the Mars Science Laboratory team withinformation about the landing site and its surroundings. This will help missionscientists interpret the rover's ground-level views and help them plan its initial drives.

"Eachof the 10 science instruments on the rover has a role in making the missionsuccessful," said Curiosity's chief scientist John Grotzinger of theCalifornia Institute of Technology in Pasadena, Calif. "This one will giveus a sense of the terrain around the landing site and may show us things wewant to study. Information from these images will go into our initial decisionsabout where the rover will go."

Hundredsof images taken by the camera will show features smaller than what can bediscerned in images taken from orbit. The set of images from higher altitude toground level will allow scientists to pinpoint Curiosity's location even beforean orbiter can photograph the rover on the surface.

"Withinthe first day or so, we'll know where we are and what's near us," Malinsaid. "MARDI doesn't do much for six-month planning ? we'll use orbitaldata for that ? but it will be important for six-day and 16-day planning."

Butwait, there's more

Combininginformation from the descent images with information from the spacecraft'smotion sensors will also enable calculations of wind speeds that affect thespacecraft on its way down, giving scientists important atmospheric sciencemeasurements.

Thedescent data will then play a part in designing and testing future landing systems for Mars that could increase control and hazardavoidance.

Afterlanding, the Mars Descent Imager will offer the capability to obtain detailedimages of the ground beneath the rover in order to precisely track itsmovements, or for purposes of geologic mapping. Whether this capability isactually used will be decided by the science team, who will be tasked withmanaging budget, data and time constraints.

Lastmonth, spacecraft engineers and technicians re-installed the Mars DescentImager onto Curiosity for what is expected to be the final time as part of the assembly and testing of the rover and its flight system at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratoryin Pasadena.

Besidesthe rover itself, the flight system includes the cruise stage for operationsbetween Earth and Mars, and the descent stage for getting the rover from thetop of the Martian atmosphere safely to the ground.

- Images ? Rovers on Mars

- Most Amazing Mars Rover Discoveries

- Video ? Building the Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity

Denise Chow is a former Space.com staff writer who then worked as assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. She spent two years with Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions, before joining the Live Science team in 2013. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University. At NBC News, Denise covers general science and climate change.