Saturn Lightning Superbolts Revealed in New Photos

NASA's Cassini spacecraft has revealed new photographs of powerfullightning flashing on Saturn after steadily watching a particularly stormy partof the ringed planet, according to a new study.

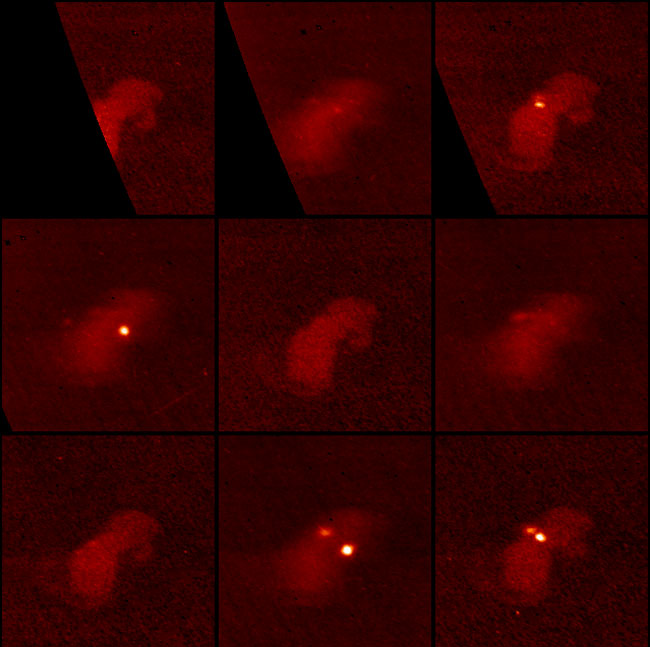

Lightning, a common phenomenon on Earth, has been an elusive target on Saturn, at times only indirectly identified by previous studies. The new photos show aseries of bright flashes against a cloudy backdrop.

"We can learn the brightness and total power from theimages," the lead researcher Ulyana Dyudina told SPACE.com. "Thebrightest lightning on Earth, called superbolts ? they're very bright and verypowerful ? these are comparable in the amount of light that they emit to whatwe see on Saturn, and what we see on Jupiter as well."

In the past, lightning images have been difficult to obtainbecause the planet's nights are typically very bright due the highly reflectivenature of Saturn'srings. The light that reflects off of these rings makes it tough tovisually distinguish flashes of lightning, researchers said.

Yet, scientists who had been monitoring a section of theplanet at latitude 35 degrees south ? which is referred to as "stormalley" because of the high level of stormactivity ? had suggested the presence of thunder and lightning on Saturn.

?Additionally, Cassini's radio instruments picked up onstatic noise that likely signaled lightning coming from storm alley.

The Cassini spacecraftwas able to obtain the new images of lightning on Saturn in the period aroundAugust 2009, during the planet's equinox. For the duration of the equinox, mostof Saturn's rings are in shadow, which makes it possible to detect lightningflashes. The findings of the study were published May 15 in the journalGeophysical Research Letters.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Preliminary images of the lightning, including a shortvideo, were released earlier this year in April.

Superbolts of Saturn lightning

Cassini detected the visible lightning flashes on Saturn onAug. 17, 2009. The images were obtained by Cassini's imaging science subsystemat a latitude of about 36 degrees south and longitude of 11 degrees west over aperiod of 13 minutes.

"We had been hearing and seeing the storm, but notlightning itself for five years," said Dyudina, who is a researcher in theDivision of Geological and Planetary Sciences at California Institute ofTechnology in Pasadena, Calif. "Now we have actually seen the light fromthat lightning on Saturn's night side. And we took actual images of thelightning."

Through close analysis, the researchers determined that thelightning flashes are consistent with a single cloud flashing once per minute,and the visible energy of a single flash is actually comparable to that onEarth and Jupiter, where lightning has also been detected.

Furthermore, Cassini's data and images allowed theresearchers to measure the lightning and track where it occurs in the stormcloud.

"The spots that are produced by lightning have severalhundred kilometers width, and to produce such large diffuse spots, thelightning should be down below the clouds by about 100 to 200 kilometers (62 to124 miles)," Dyudina said. "So, this means that the lightning happensdeep into the water cloud."

This lightning, said Dyudina, has similar properties to thealien lightning on Jupiter that has been confirmed.

But, the most marked difference is in the location of Saturn'sthunderstorm itself.

"On Saturn, we have a very unique situation in which wehave just one thunderstorm at latitude 35 degrees south," Dyudina said."It's a very bright cloud ? so bright that even amateur astronomers cansee it from Earth."

The researchers noticed that the bright cloud has a tendencyto appear, then disappears for a few months, then appears again at the samelatitude and remains for another several months. In fact, the storm thatgenerated the lightning that Cassini imaged lasted from January to October in 2009.

"The gaps between the storms can be severalyears," Dyudina said. "The longest storm was nine months. But, it'salways at the same latitude and we see it on just the one cloud. This is very unique."

Gas giant lightning

In contrast, on Jupiter, lightning happens in differentplaces, and the phenomenon has been imaged at different latitudes.

Further studies will attempt to help scientists betterunderstand the formation and characteristics of this peculiarlightning on Saturn.

Dyudina and her colleagues are already in the midst ofconducting more lightning searches on Saturn, monitoring the planet for brightclouds, and trying to understand why the thunder and lightning storm occurs inone particular place.

In the meantime, this study has implications for otherplanets, where lightning may one day also be detected.

"This means that there is heat stored in the planetsafter the planet formation, and the way the planet cools is throughthunderstorms and lightning," Duydina said. "These bring lots of heatthat is down below to higher levels, and it's more efficient than justradiation. This cooling is important for the evolution of planetarysystems."

- The Wildest Weather in the Galaxy

- The Rings and Moons of Saturn

- Top 10 Extreme Planet Facts

Denise Chow is a former Space.com staff writer who then worked as assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. She spent two years with Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions, before joining the Live Science team in 2013. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University. At NBC News, Denise covers general science and climate change.