First Black Holes Starved at Birth

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The first black holes in the universe were born starving.

A new study found that the earliestblack holes lacked nearby matter to gobble up, and so lay relatively stagnantin pockets of emptiness.

The finding, based on the most detailed computer simulationsto date, counters earlier ideas that these first black holes accumulated massquickly and ballooned into the supermassiveblack holes that lurk at the centers of many galaxies today.

"It has been speculated that these first black holeswere seeds and accreted huge amounts of matter," said the study?s leader MarceloAlvarez, an astrophysicist at the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics andCosmology in California. "We're just finding out that it could be muchmore complex than that."

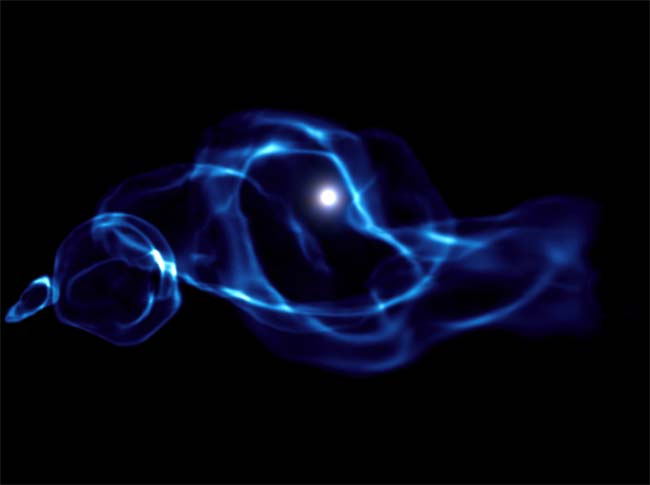

Alvarez and colleagues constructed a computer simulation ofthe earlyuniverse based on measurements of the cosmic background radiation left overfrom the BigBang, which scientists think started the universe 13.7 billion years ago.The model used these starting conditions, and the laws of physics, to watch howthe universe may have evolved.

The study is detailed in an upcoming issue of TheAstrophysical Journal Letters. The Kavli Institute is at the Stanford LinearAccelerator Center (SLAC) National Accelerator Laboratory in Menlo Park, Calif.

Hungry, hungry black holes

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In the simulated young universe, clouds of gas condensed toform the first stars. Because of the chemistry of the gas at this time, thesestars were much larger than today's typical stars and weighed more than ahundred times the mass of the sun.

After a short time these massive, hot stars exhausted theirinternal fuel and collapsed under their own immense weight to form black holes.But because the huge stars had emitted such strong radiation when they werestill alive, they had blown most nearby gas away and left very little matter tobe eaten by the resulting black holes.

Rather than swiftly swallowing large chunks of matter andgrowing into larger black holes, the simulation showed that the universe'sfirst black holes grew by less than one percent of their original mass over thecourse of a hundred million years.

The scientists don't know what eventually became of thesehungry black holes.

"It is possible that they merged onto larger objects thatthen themselves collapsed into black holes, bringing these first black holesalong for the ride," Alvarez told SPACE.com. "Another possibility isthat they got kicked out of the galaxy by interactions with other objects andwould just be floating around in the halo of the galaxy now."

Whatever happened, the researchers think that thesetrailblazing black holes may have played an important part in shaping theevolution of the first galaxies.

Even on a diet, the black holes likely produced significantamounts of X-rayradiation, which is released when mass falls onto a black hole. Thisradiation could have reached gas even at a distance and heated it up totemperatures too high to condense and form stars. Thus the first black holesmay have prevented star formation in their vicinity.

These hot gas clouds may have carried on for millions ofyears without creating stars, and then eventually collapsed under their ownweight to create supermassive black holes.

Though this idea is only speculation, the researchers areintrigued by the possible effects of the universe's first black holes.

"This work will likely make people rethink how theradiation from these black holes affected the surrounding environment," saidJohn Wise of NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. "Blackholes are not just dead pieces of matter; they actually affect other parts ofthe galaxy."

- Video - A Starving Black Hole

- Video: Black Holes - Warpers of Time and Space

- All About Black Holes

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.