Space Shuttles May Have to Fly Beyond 2010, Panel Says

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

This story was updated at 11:16 a.m. EDT.

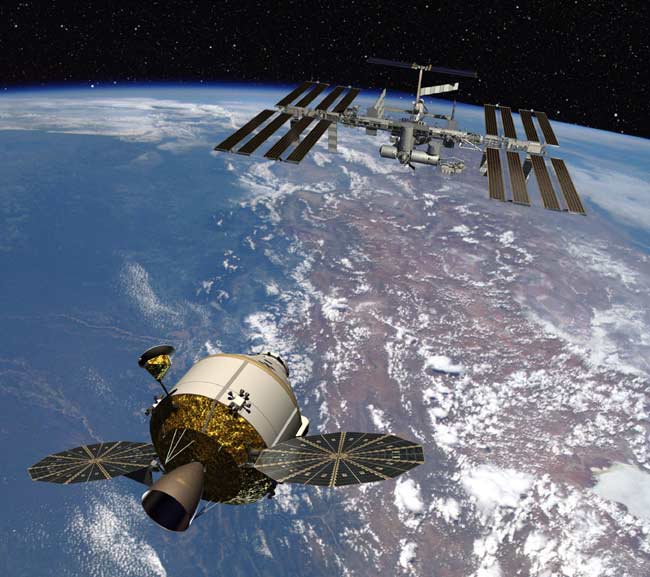

NASA will likely have to continue flying its aging spaceshuttle fleet beyond its planned 2010 retirement date in order to completeconstruction of the International Space Station, a presidential panel saidTuesday.

Former astronaut Sally Ride, a member of the Review of U.S.Human Space Flight Plans Committee, said that it was unlikely NASA could meetthe current deadline of retiring thespace shuttle by next year, as is currently planned. The first operationalflights of the agency?s replacement for the shuttle, the Orion spacecraft, may alsobe delayed a year or so beyond its 2015 target, she added.

Article continues belowThe reviewpanel was appointed by the White House Office of Science and Technology Policyto reevaluate NASA's current direction, including the goal of returning humansto the moon by 2020. It is expected to issue a report in August.

Ride and the other members of the panel's subgroup examiningplans for the International Space Station and space shuttle predicted that thecurrently scheduled shuttle flights will take until about March 2011 tocomplete.

"There's little margin remaining in thecurrent manifest," Ride said. "NASA is considering safetyfirst" when deciding when to launch shuttle missions, but "the closeryou get to a hard and fast deadline, the more difficult that becomes."

NASA plans to launch seven more shuttle missions after thecurrent flight of Endeavour, which undocked from the station Tuesday, tocomplete construction of the orbiting lab.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The manifest as currently stated through 2010 isexceptionally ambitious and requires a flight rate that is approximately twicewhat the post Columbia flight rate has been," said review panel memberCharles Kennel, chair of the National Academies Space Studies Board.

The panel also proposed that the International SpaceStation's working lifetime be extended through at least 2020, beyond theplanned decommissioning in 2015, which is only five years after it is fullyassembled.

"We think all of the options going forward shouldinclude an extension of ISS in some form," Ride said.

The panel felt that it would be a poor return on investmentto utilize the station for only a short time after spending about 25 years tobuild it. In addition, the other international partner countries working on thestation have all strongly pushed for an extension to the laboratory'slifetime.

Extending the launch plans to mid-2011 would add about $1.5billion in unbudgeted costs for NASA, though.

Additionally, the review panel estimated that NASA's nextgeneration human space exploration program, Constellation, is likely to bedelayed past its planned 2015 launch date. TheConstellation spaceship, called Orion, will probably first launch humans atleast a year or two late because of budget cuts and technical difficulties.

"It is likely that the initial operation capability forthe next human rated launch vehicle will come no earlier than 2017, and thereis a significant probability that it will be several years," Kennel said.

Ride blamed the Constellation delay on a gap between thegoals laid out for the program by former President George W. Bush, and the budget allocated to NASAby Congress to achieve them.

"NASA has not been given the resources to support thisvision," she said. "You can't expect the agency to achieve grand andglorious goals" and then not provide the necessary funding, she said.

- Video - NASA's Constellation Journey Begins: Part 1, Part 2

- End in Sight: Final Space Shuttle Missions Slated

- Image Gallery - The First 100 Space Shuttle Flights

Editor's note: This article was updated to correct thecost of extending shuttle flights through March 2011.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.