Oddball 'Blue Stragglers' Are Stellar Cannibals

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Astronomershave found what they say is the strongest evidence yet that a mysterious classof stars known as "blue stragglers" are the result of stellarcannibalism.

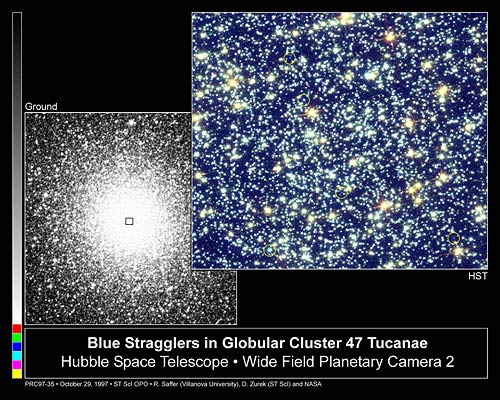

Bluestragglers are found throughout the universe in globularclusters ? which typically are collections of about 100,000 stars, tightlybound by gravity. Because all the stars in these clusters are thought to havebeen born at the same time, they should all be the same age, but bluestragglers appear to be younger than their cluster peers.

The originof these strange, massive stars has been a longstanding mystery, said studyleader Christian Knigge of Southampton University in England.

"Theonly thing that was clear is that at least two stars must be involved in thecreation of every single blue straggler, because isolated stars this massivesimply should not exist in these clusters," Knigge added.

Since theseoddball stars were first discovered more than half a century ago, two competingexplanations for their formation emerged: "that blue stragglers werecreated through collisionswith other stars; or that one star in a binary system was 'reborn' bypulling matter off its companion," said study team member Alison Sills ofthe McMaster University in Canada.

A 2006study examined the chemical signatures of 43 blue stragglers in theglobular cluster 47Tucanae, and found that six of the unusual stars had less carbon and oxygenthan the others. The anomaly indicated that their surface material had beensucked from the deep interior of a parent star in a binary system.

The newstudy, detailed in the Jan. 15 issue of the journal Nature, provideseven more evidence in favor of the stellar cannibalism idea.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Theresearchers looked at blue stragglers in 56 globular clusters and found thatthe total number of blue stragglers in a given cluster didn't match thepredicted collision rate ? dispelling the theory that blue stragglers arecreated through collisions with other stars.

But therewas a connection between the total mass contained in the core of the globularcluster and the number of blue stragglers observed within it. Since moremassive cores also contain more binary stars, the researchers could infer arelationship between blue stragglers and binaries in globular clusters. Thisconclusion is also supported by preliminary observations that directly measuredthe abundance of binary stars in cluster cores.

"Thisis the strongest and most direct evidence to date that most blue stragglers,even those found in the cluster cores, are the offspring of two binarystars," Knigge said. Though there is still plenty of research on thesestars to do.

"Inour future work we will want to determine whether the binary parents of bluestragglers evolve mostly in isolation, or whether dynamical encounters withother stars in the clusters are required somewhere along the line in order toexplain our results," Knigge said.

The studywas funded in part by the United Kingdom's Science and Technology FacilitiesCouncil.

- Video: Sorting Stars

- Top 10 Star Mysteries

- Vote: The Strangest Things in Space

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.