Sunlight Splits Asteroids into Pairs

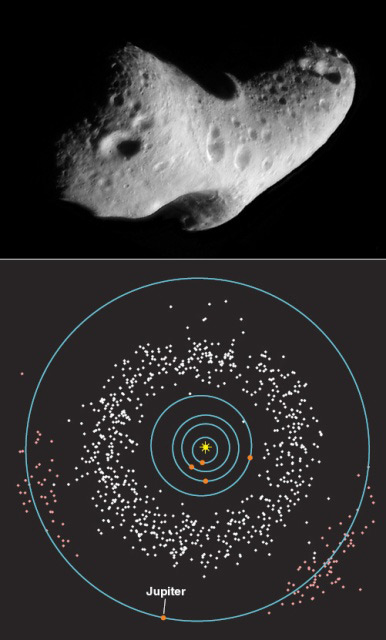

Asteroids often come in pairs, with the two objects spinningaround each other. Now scientists say sunlight could be the cause of thesebinary boulders.

A new study suggests energy from the sun can spin up asingle asteroid until it ejects material that becomes a separate satellite.

Astronomers first discovered these strangeasteroid pairs 15 years ago, and have been puzzled about what causes them.Now scientists have created a computer model that matches what they see.

"So far our results match the properties of binaryasteroids quite well," said astronomer Kevin Walsh of the Observatoire dela Cote D'Azur in Nice, France. Walsh led the study when he wasa graduate student at the University of Maryland, working with his advisorDerek Richardson and Patrick Michel of the Cassiope?e, University ofNice-Sophia Antipolis, in Nice.

Lots of them

Binary asteroid systems are surprisingly common ? they seemto make up about 15 percent of near-Earth asteroids, or those that come nearour planet's orbital path around the sun. (Most asteroids orbit in a beltbetween Mars and Jupiter and are too far from Earth for detailed measurements).

In order to probe how these binary setups are spawned, the astronomersmodeled asteroids as "rubble piles," or chunks of rock held togetherby gravity, and watched what happened over time. The thinking is that manyasteroids are not solid objects but rather loose conglomerations prone to rearrangementand pulling apart.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

When sunlight hits one of these piles, the material absorbssome of the radiation and then re-emits it at a slightly different angle,giving itself a small push in angular momentum, Walsh said. This change cancause the asteroid to spin up slightly in what's called the YORPeffect (named for the scientists who discovered it: Yarkovsky-O'Keefe-Radzievskii-Paddack).

The YORP effect is also known to slow down the spin of someasteroids and tweak the orbits of others, sending them flying in slightly differentdirections, and occasionally toward another planet, such as Earth.

Over time, as an asteroid spins up, its shape will becomemore spherical with an increasingly circular equator where mass begins to buildup. Eventually, if the rock spinsfast enough, the force outward from the rotation will overpower thegravitational pull inward and material will eject along the equator to form anew small satellite. The two asteroids then circle each other in binary pairs.

"Ours was the first model that could actually simulatean asteroid being spun up to its maximum spin rate by the YORP effects,"Walsh told SPACE.com. "We made the first step and showed YORP canmake systems that look exactly like what we observe."

Not the only way

The team compared their model's predictions to observationsof a binary asteroid called KW4 made by astronomers using the Arecibo radiotelescope in Puerto Rico.

"It's by far the best observation we have of any singleasteroid," Walsh said. "Globally, observations suggest that nearlyall the small near-Earth binary systems are similar to this KW4 system. Werecreate its shape pretty closely with a lot of our simulations."

Though the scientists say the YORP effect isn't the only wayto create binary systems ? they could also be formed by impacts or by tidalforces from passing another large body ? they think the process they've modeledaccounts for most of the known asteroid pairs.

- VIDEO: Killer Asteroids and Comets

- IMAGES: Asteroid Gallery

- All About Asteroids

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.