The Quest for the Lunar GRAIL

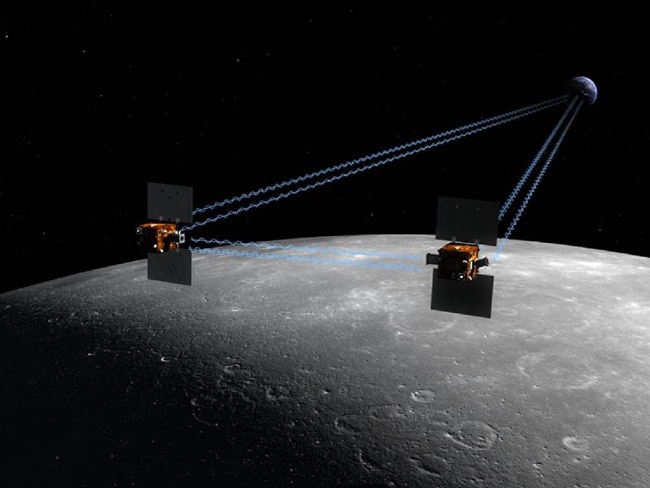

Twin NASA spacecraft will attempt to map the mostgravitationally lumpy body in our solar system — Earth?s moon.

Asteroid impacts from billions of years ago left denseburied pockets of material under the lunar surface, which can exert extra gravitationalpull on spacecraft orbiting the moon.

"This mission will give us the most accurate globalgravity field to date for any planet, including Earth," said Maria Zuber,the MIT physicist leading the Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL)mission.

Scientists still don?t know what material forms the densemass concentrations (mascons). Some of the mass may come from denser lavafilling ancient impact craters, or iron-rich molten material seeping upwards tothe moon?s crust.

Whatever the case, the gravitational effect is so strongthat an astronaut dangling a weight on the end of a string near a mascon wouldsee it hang a third of a degree off vertical, pointing toward the center of thelunar formation.

Such gravitational anomalies make low lunar orbitsunusually treacherous and force spacecraft to constantly adjust their orbits. Onesub-satellite released during NASA?s Apollo 16 mission in 1972 crashed just 35days later, as its circular orbit decayed into a more elliptical shape thateventually caused it to impact.

?If you take out the five major mascons on the near sideof the moon, orbits are much more stable,? said Alex Konopliv, a GRAILplanetary scientist at NASA?s Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena, Calif. He addedthat the far side of the moon has smaller mascons, which have weakergravitational pulls.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Even the LunarProspector mission in 1999 had to use up fuel doing constant coursecorrections to stay in orbit, before NASA intentionally crashed the orbiterinto a crater.

GRAIL is designed to gauge the moon?s gravitational graspby flying two spacecraft in lunar orbit, one behind the other by 124 miles (200km), for about three months. A microwave ranging system will allow scientiststo precisely measure the distance between the spacecraft as it contracts andexpands based on the gravitational tugs of mascons.

?The baseline plan is to have a 50 kilometer (30 mile)high orbit,? Konopliv told SPACE.com. However, he noted that the actualorbit would vary between 30 and 70 kilometers due to the gravitationalinfluence of the mascons, requiring GRAIL to maneuver back to its originalstarting point every 30 days.

After GRAIL does its work, ?we?ll be able to navigateanything you want anywhereon the moon you want,? Zuber said.

That will help mission planners choose precise orbitsthat avoid the worst of the gravitational anomalies. NASA already knows of fourorbits where spacecraft can maintain almost indefinite lunar orbits, includingone that almost passes over the lunar poles.

GRAIL will also aid NASA in choosing how to approach themoon for the planned 2020 landings of its astronaut-carrying Altair landers onthe moon?s far side and polar regions ? places where the lunar gravitationalfield remains least understood. Scientists could then use the gravity map ofthe moon to better examine the lunar crust and core.

The mission idea for GRAIL came from the success of theU.S.-German Earth observing Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE),which launched in 2002. GRACE gauges gravity changes related to the melting ofice at the poles and changes in ocean circulation.

Neither Earth nor Venus contain mascons like those on themoon, but similar features do appear on Mars. NASA has already said that the2011 GRAIL mission will likely inspire future space quests to do gravitationalmapping.

- Video: A New Era of Space Exploration

- Top 10 Apollo-Era Discoveries

- Top 10 Cool Moon Facts

Jeremy Hsu is science writer based in New York City whose work has appeared in Scientific American, Discovery Magazine, Backchannel, Wired.com and IEEE Spectrum, among others. He joined the Space.com and Live Science teams in 2010 as a Senior Writer and is currently the Editor-in-Chief of Indicate Media. Jeremy studied history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania, and earned a master's degree in journalism from the NYU Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. You can find Jeremy's latest project on Twitter.