Universe Loaded With Natural Magnifying Glasses

One of the best tools astronomers have to glimpse thedistant universe is a technology that nature invented. Cosmic magnifyingglasses called gravitational lenses help scientists zoom in on far-away scenes theycould never spot otherwise.

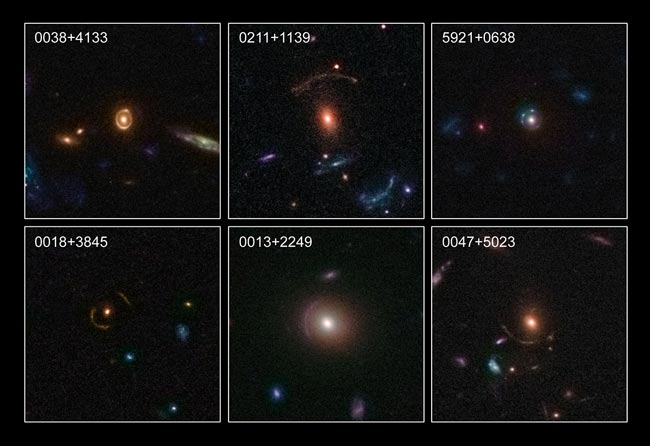

In a recent survey of a section of the universe, researcherscounted 67 new gravitational lenses, leading them to believe there are nearlyhalf a million similar lenses in the rest of the universe.

"Gravitational lenses amplify the signal," said PeterCapak, an astronomer at California Institute of Technology who worked on thestudy. "It's like a second telescope in front of your telescope. We cansee things that are much fainter than we can normally see."

These natural telescopes are created when massive objectsdistort the space-time around them through the strength of their gravitationalpull, causing light to bend as it travels through the warped space.

If a gravitationallens lies between us and a distant object, then the image of the object wesee can be distorted and magnified.

In the rare case that a gravitational lens is perfectlyaligned between Earth and a distant object, "typically you can get atleast a factor of 10 ? 50 magnification," said Jean-Paul Knieb, an astronomerat Laboratoire d?Astrophysique de Marseille, France, leader of the study.

The effect was predictedin the 1930s by Einstein's general theory of relativity, and was first observedin 1979.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The 67 newly discovered lenses are caused by large galaxies,although clusters of galaxies often produce strong gravitational lenses too.

A team of astronomers used the NASA/ESA Hubble SpaceTelescope, along with follow-up observations from the ground, to image a 1.6square degree field of sky (about nine times the area of the full Moon) ingreat detail. The researchers then pored over the images by eye to spot thetell-tale circular warping signatures of gravitational lenses.

In addition to giving scientists a better idea of how manygravitational lenses are out there, the discovery will help researchers studythe spread of darkmatter around the galaxies causing the lenses.

"The main thing the gravitational lenses do for us isthey allow us to study the mass distribution in individual galaxies,"Capak told SPACE.com. "A lot of the mass is contained in darkmatter. We want to understand how the dark matter is distributed."

By analyzing patterns in the warping of space-time caused bythe gravitational lenses, the scientists hope to gain a better understanding ofthe structure of galaxies.

"You can think of the lenses as glass beads," Capaksaid. "If you hold up a glass bead and look thorough it, it distorts thepicture behind it. The shape of the glass bead is what's causing the differentdistortions. The shape of the mass distribution in galaxies is distorting thebackground in different ways."

- Top 10 Strangest Things in Space

- Vote: The Best of the Hubble Space Telescope

- Image Gallery: Hubble's Latest Views of the Universe

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.