Earth's Magnetic Field Nearly Disappeared 565 Million Years Ago

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Five hundred and sixty-five million years ago, Earth's magnetic field almost disappeared.

But a geological phenomenon might have saved it, a new study suggests. Earth's then-liquid core likely began to solidify around that time, which strengthened the field, the group reported yesterday (Jan. 28) in the journal Nature Geoscience. This is important because the magnetic field protects our planet and its inhabitants from harmful radiation and solar winds — streams of plasma particles thrown our way by the sun.

Scientists figured out what our planet's core was like back then by looking at crystals the size of grains of sand.

They picked up samples of plagioclase and clinopyroxene — minerals that were formed 565 million years ago — in what is now eastern Quebec, Canada. These samples contain tiny magnetic needles about 50 to 100 nanometers in size, which, in molten rock, orient themselves in the direction of the magnetic field at the time. [Shine On: Photos of Dazzling Mineral Specimens]

"Those tiny magnetic particles are ideal magnetic recorders," said co-author John Tarduno, the chair of the Earth and Environmental Sciences department and a professor at the University of Rochester in New York. "When they cool, they lock in a record of Earth's magnetic field that's maintained for billions of years."

So, by sticking the crystals in a magnetometer, the researchers were able to figure out that the particles' charge was very low. In fact, 565 million years ago, Earth's magnetic field was over 10 times weaker than what it is today — the weakest ever documented.

Further, the measurements showed that the frequency of north and south pole reversals was very high. All of this suggests that "the field was extremely unusual," Tarduno told Live Science. "We were at this critical point where the dynamo almost collapsed completely." (The geodynamo is the process that maintains and grows the magnetic field.)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But then the geodynamo got a kick start once more — from the very core of our planet.

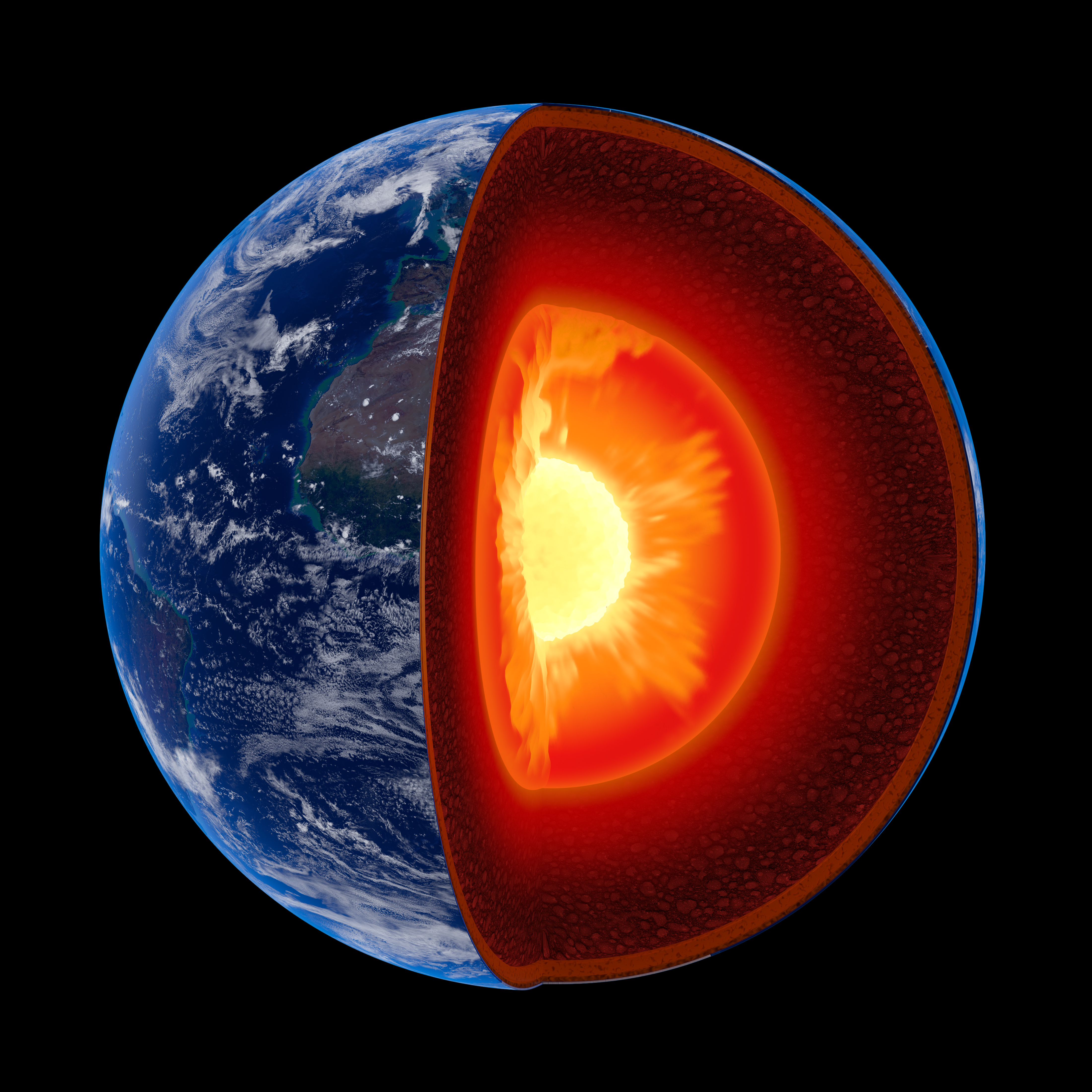

In Earth's early years, the core was all liquid. But at some point — guesses range from between 2.5 billion years to 500 million years ago — iron began to cool and freeze into a solid layer in the middle of the planet. As the inner core solidified, lighter elements like silicon, magnesium and oxygen were kicked out into the outer, liquid layer of the core, creating a movement of fluid and heat called convection. This movement of fluid in the outer core kept charged particles moving, creating an electrical current, which in turn created a magnetic field.

This convection drives and maintains the magnetic field even today. Earth's inner core is continuing to solidify and will do so for billions of years to come.

The researchers "present intriguing paleomagnetic measurements" that suggest a weak geodynamo existed 565 million years ago, which meant that the core was fully liquid, wrote Peter Driscoll, an earth and planetary scientist at the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington, D.C., who was not a part of the research, in a commentary that accompanied the study. If their theory holds true, "the inner core may have occurred right in the nick of time to recharge the geodynamo and save Earth's magnetic shield."

Shortly after this time, the Cambrian explosion occurred and complex animals emerged across the planet. "One can speculate — and there have been some speculations — that a weaker magnetic field may have some relationship to these evolutionary events," Tarduno said. That is because a weaker field might allow more radiation to get through, which could cause DNA damage and higher mutation rates, which in turn, might have lead to more species evolving.

But this is mere speculation, Tarduno said. When Earth's magnetic field weakens a bit during events such as magnetic reversals (where the north and south poles flip), for instance, there's no evidence that species are affected, he added.

Originally published on Live Science.