'Meet Ultima Thule': 1st Color Photo of New Horizons Target Reveals a Red 'Snowman'

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

We now know what Ultima Thule looks like, and it's not a bowling pin.

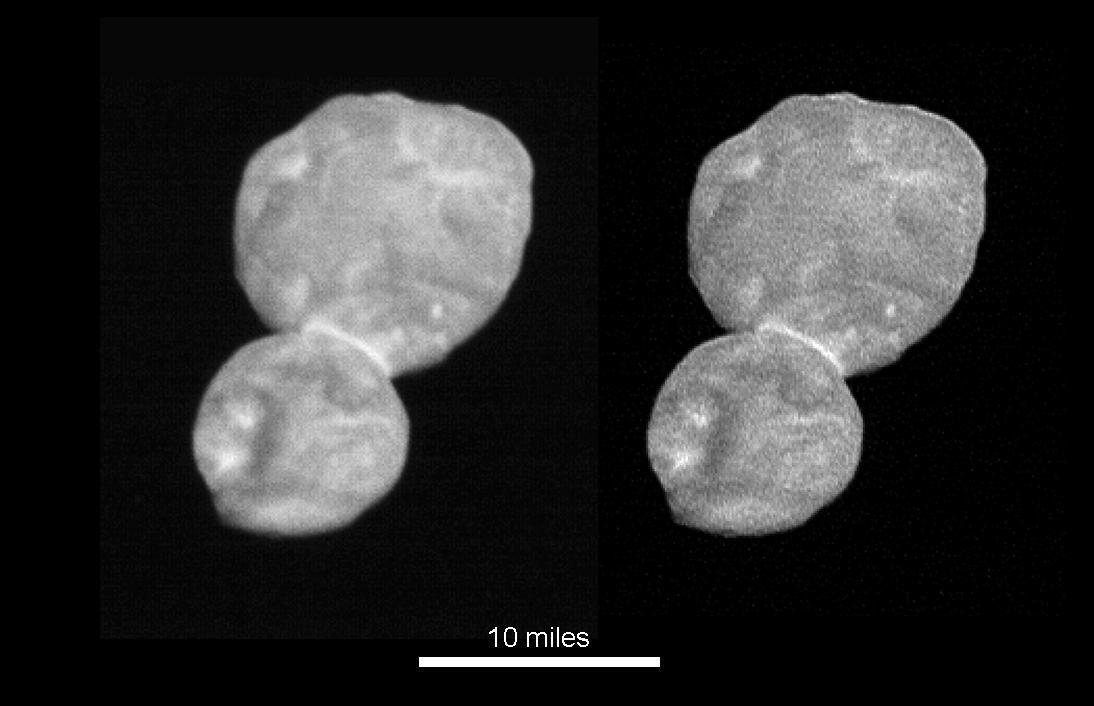

The first resolved photos of Ultima Thule have come in from NASA's New Horizons spacecraft, which zoomed past the frigid faraway object just after midnight yesterday (Jan. 1). The historic imagery reveals that the 21-mile-long (33 kilometers) Ultima is a "contact binary" composed of two roughly spherical lobes.

Photos taken by New Horizons over the previous week or so had suggested that these two lobes are connected by a relatively narrow neck. But the new imagery shows they're glommed tightly together, dashing earlier analogies. [New Horizons at Ultima Thule: Full Coverage]

"That bowling pin is gone," New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colorado, said during a news conference today (Jan. 2). "It's a snowman, if it's anything at all."

The two lobes — dubbed, appropriately enough, "Ultima" (the larger lobe) and "Thule" — are red, their icy surface material likely discolored by deep-space radiation, mission team members said. Similar processes are responsible for the reddish hue of much of Pluto's surface, as well as the northern reaches of that dwarf planet's largest moon, Charon (which apparently got this reddish material from Pluto).

Ultima and Thule were once separate, free-flying objects; they coalesced long ago, just after the solar system's birth, mission team members said. This union was not violent; the two bodies came together at about walking speed, in a meetup more akin to a spacecraft docking than to a collision, said Jeff Moore of NASA's Ames Research Center, the leader of New Horizons' geology and geophysics team.

Countless objects like Ultima Thule — which is officially known as 2014 MU69 — eventually built up our solar system's planets. But that didn't happen with Ultima Thule, which has remained pristine for eons in a cosmic deep-freeze, more than 4 billion miles (6.4 billion km) from the sun.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

That's why New Horizons team members were so keen to fly by the object, and why they're so excited by the early science returns from the epic New Year's Day encounter.

"We think what we're looking at it is perhaps the most primitive object that has yet been seen by any spacecraft, and may represent a class of objects which are the oldest and most primitive objects that can be seen anywhere in the present solar system," Moore said during today's news conference.

The new imagery, dramatic though it may be, is just the tip of the Ultima Thule iceberg. The photos unveiled by the New Horizons team today were taken before closest approach, from distances of about 85,000 miles (137,000 km) and 18,000 miles (28,000 km).

At the peak of the encounter, New Horizons got within a mere 2,200 miles (3,500 km) of Ultima Thule. So, prepared to be wowed by higher-resolution photos in the coming days and weeks.

"It's just going to get better and better," Stern said.

The $700 million New Horizons mission launched in January 2006, tasked with performing the first-ever flyby of Pluto. The probe aced this objective in July 2015, showing the dwarf planet to be a world of surprisingly complex and varied landscapes.

The Ultima Thule encounter — the most-distant planetary flyby in history — is the centerpiece of New Horizons' extended mission, which runs through 2021. The spacecraft has enough power and fuel left to potentially perform a flyby of yet another distant object, if NASA ends up approving another mission extension, Stern said.

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate) is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us @Spacedotcom or Facebook. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.