Landing Site on Asteroid Ryugu Chosen for Japan's Hayabusa2 Mission

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

We now know where a Japanese asteroid-sampling probe's lander will touch down this October.

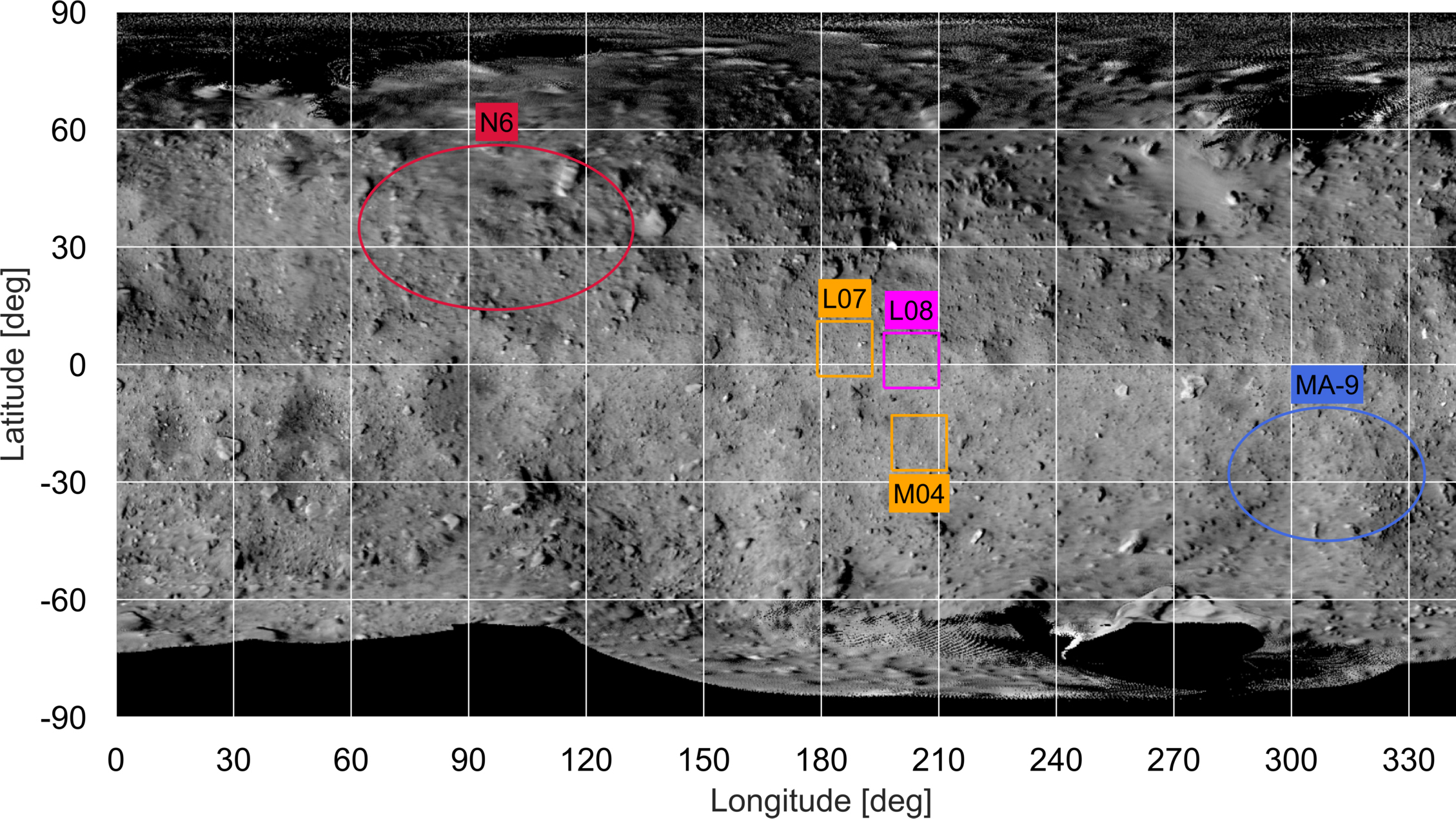

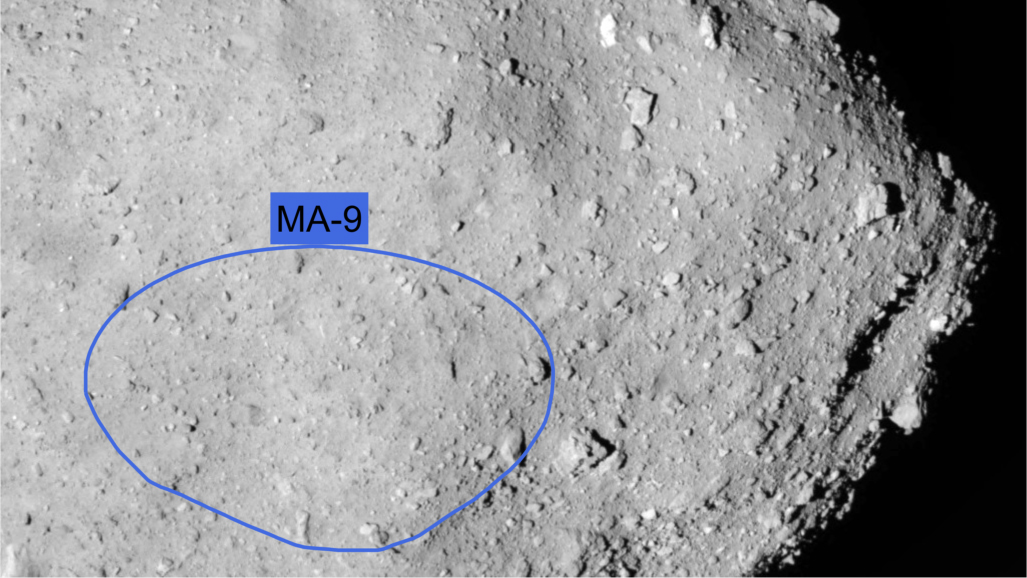

The Hayabusa2 spacecraft's Mobile Asteroid Surface Scout (MASCOT) will land at a site in the asteroid Ryugu's southern hemisphere dubbed MA-9, mission officials announced today (Aug. 23).

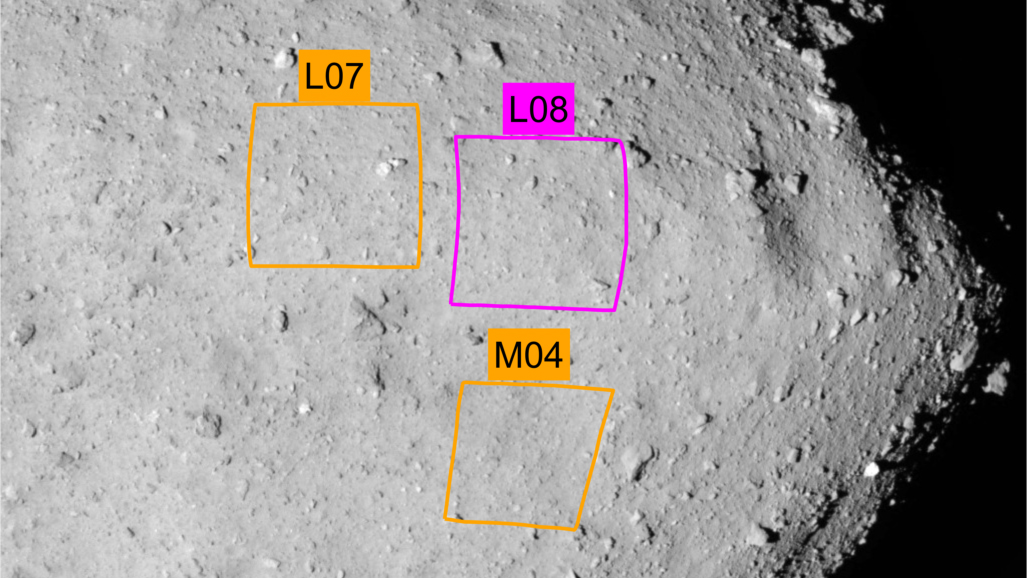

MA-9 won out over nine other finalists because it offered the best combination of scientific potential and accessibility, MASCOT team members said. [Japan's Hayabusa2 Asteroid Sample-Return Mission in Pictures]

"From our perspective, the selected landing site means that we engineers can guide MASCOT to the asteroid's surface in the safest way possible, while the scientists can use their various instruments in the best possible way," MASCOT project manager Tra-Mi Ho, of the DLR Institute of Space Systems, said in a statement. (DLR is the German Aerospace Center, which operates MASCOT with support from the French space agency, CNES.)

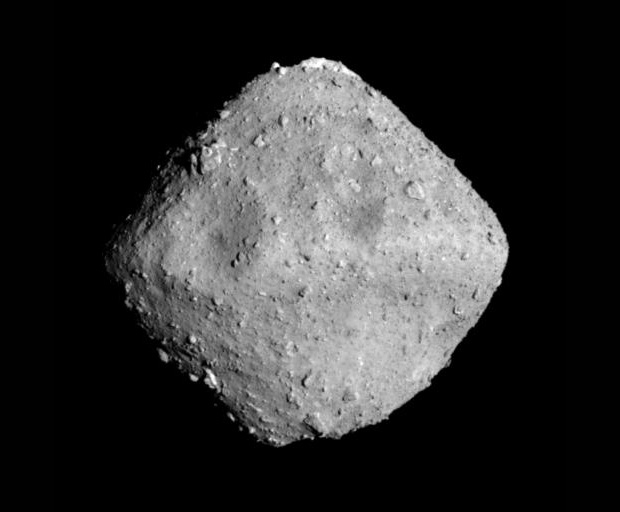

MA-9 features relatively fresh, pristine surface material that hasn't been exposed to cosmic radiation for long compared to other parts of the 3,000-foot-wide (950 meters) asteroid, team members said. And Hayabusa2 will drop three small rovers onto patches of the space rock's northern hemisphere, so a southern site for the 22-lb. (10 kilograms) MASCOT will give the mission greater coverage of the space rock, they added.

In addition, MA-9 isn't quite as boulder-studded as most other Ryugu regions. That doesn't mean landing there will be a breeze on Oct. 3, however.

"But we are also aware: There seem to be large boulders across most of Ryugu's surface and barely [any] surfaces with flat regolith," Ho added. "Although scientifically very interesting, this is also a challenge for a small lander and for sampling."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The $150 million Hayabusa2 mission launched in December 2014 and arrived at Ryugu on June 27 of this year. If all goes according to plan, the spacecraft will study the big asteroid from orbit for another 16 months and also drop down several times to grab samples of Ryugu material.

Meanwhile, MASCOT and the three tiny, hopping rovers — known as Minerva-II-1a, Minerva-II-1b and Minerva-II-2 — will gather a variety of information about the asteroid from its surface. (Minerva-I flew aboard Japan's first asteroid-sampling mission, the original Hayabusa, which returned grains from the space rock Itokawa to Earth in 2010.)

The Hayabusa2 orbiter is scheduled to depart from Ryugu in December 2019. The capsule containing the mission's asteroid samples will come down to Earth a year later, in December 2020.

Hayabusa2 isn't the only asteroid-sampling project underway. NASA's $800 million OSIRIS-REx (Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, Security, Regolith Explorer) mission is on its final approach toward the asteroid Bennu, and should arrive in orbit around the 1,650-foot-wide (500 m) rock this December. OSIRIS-REx's samples are due to land on Earth in September 2023.

Both Hayabusa2 and OSIRIS-REx aim to help scientists better understand asteroid composition and structure, the early history and evolution of the solar system, and the role space rocks may have played in helping life get a start on Earth.

Bringing pristine samples of asteroid material back to Earth will allow researchers to tackle such questions efficiently and effectively, team members from both missions have said. Scientists can perform many more experiments and investigations using well-equipped labs around the world than a robotic probe could conduct all by itself in deep space.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.