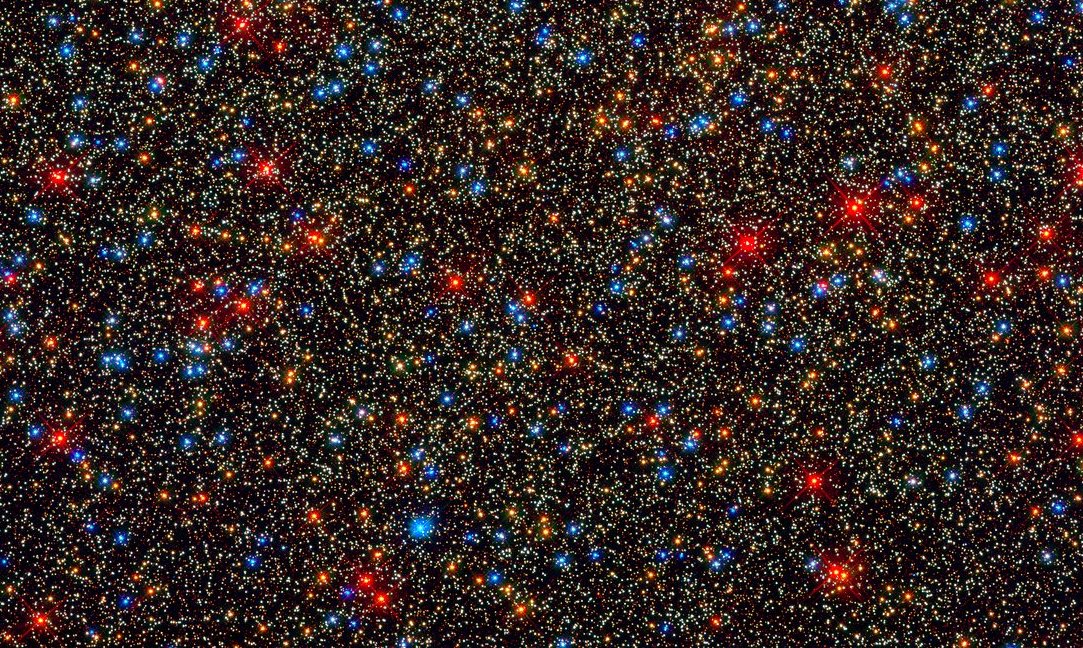

Omega Centauri Is a Terrible Place to Look for Habitable Planets

Omega Centauri may be the brightest among the dense collections of stars known as globular clusters, but it probably doesn't contain many habitable worlds, a new study suggests.

Researchers hunting for potentially habitable exoplanets in Omega Centauri found that the close proximity of neighboring stars would make it difficult for the cluster to host worlds capable of holding on to liquid water.

Globular clusters are large, compact, spherical collections of stars orbiting the Milky Way. Omega Centauri, which contains an estimated 10 million stars, lies only about 16,000 light-years from Earth, making it a relatively close target for observations by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope. [10 Exoplanets That Could Host Alien Life]

"Despite the large number of stars concentrated in Omega Centauri's core, the prevalence of exoplanets remains somewhat unknown," lead researcher Stephen Kane, an exoplanet expert at the University of California, Riverside, said in a statement. "However, since this type of compact star cluster exists across the universe, it is an intriguing place to look for habitability."

Kane and Sarah Deveny, a graduate student at San Francisco State University, used Hubble to home in on 350,000 stars in Omega Centauri whose temperature and age suggest they could potentially host life-bearing planets.

For each star, the duo calculated the habitable zone, the just-right region around a star that's neither too hot nor too cold for liquid water, a key ingredient for life as we know it. Most of the stars in Omega Centauri are red dwarfs, small but long-lived stars whose habitable zones are much closer in than the one surrounding our own larger sun.

"The core of Omega Centauri could potentially be populated with a plethora of compact planetary systems that harbor habitable-zone planets close to a host star," Kane said. He pointed out that the system TRAPPIST-1, a miniature version of our own solar system around a red dwarf, is viewed as "one of the most promising places to look for alien life."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Previous studies had suggested that a globular cluster might be the first place where intelligent life is identified in the galaxy. That's because the roughly 150 clusters around the Milky Way are about 10 billion years old, with stars roughly the same age, giving life plenty of time to emerge and evolve.

Unfortunately, the large but cozy environment of Omega Centauri works against hopes for habitability. Even compact planetary systems would struggle to exist in the core of the cluster, where stars lie an average of 0.16 light-years apart, the new study suggests.

Earth's sun, by contrast, sits a comfortable 4.22 light-years from its nearest neighbor, the red dwarf Proxima Centauri. The crowded nature of the cluster's core means a star would encounter a neighbor about once every 1 million years, during which time the interloper's gravity could easily strip away planets.

"The rate at which stars gravitationally interact with each other would be too high to harbor stable habitable planets," Deveny said in the same statement.

That's a bad sign for clusters where similar or higher encounter rates could lead to the same conclusion, she said. But in clumps where stars are spread farther apart, exoplanets could still manage to survive.

"Studying globular clusters with lower encounter rates might lead to a higher probability of finding stable habitable planets," Deveny said.

The study has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal. You can read it for free at the online preprint site arXiv.org.

Follow Nola Taylor Redd at @NolaTRedd, Facebook, or Google+. Follow us at @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky