Losing Darkness: Satellite Data Shows Global Light Pollution On the Rise

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Around the globe, in both developed and developing nations, Earth's night skies are being filled with artificial light more and more each year, according to a new study.

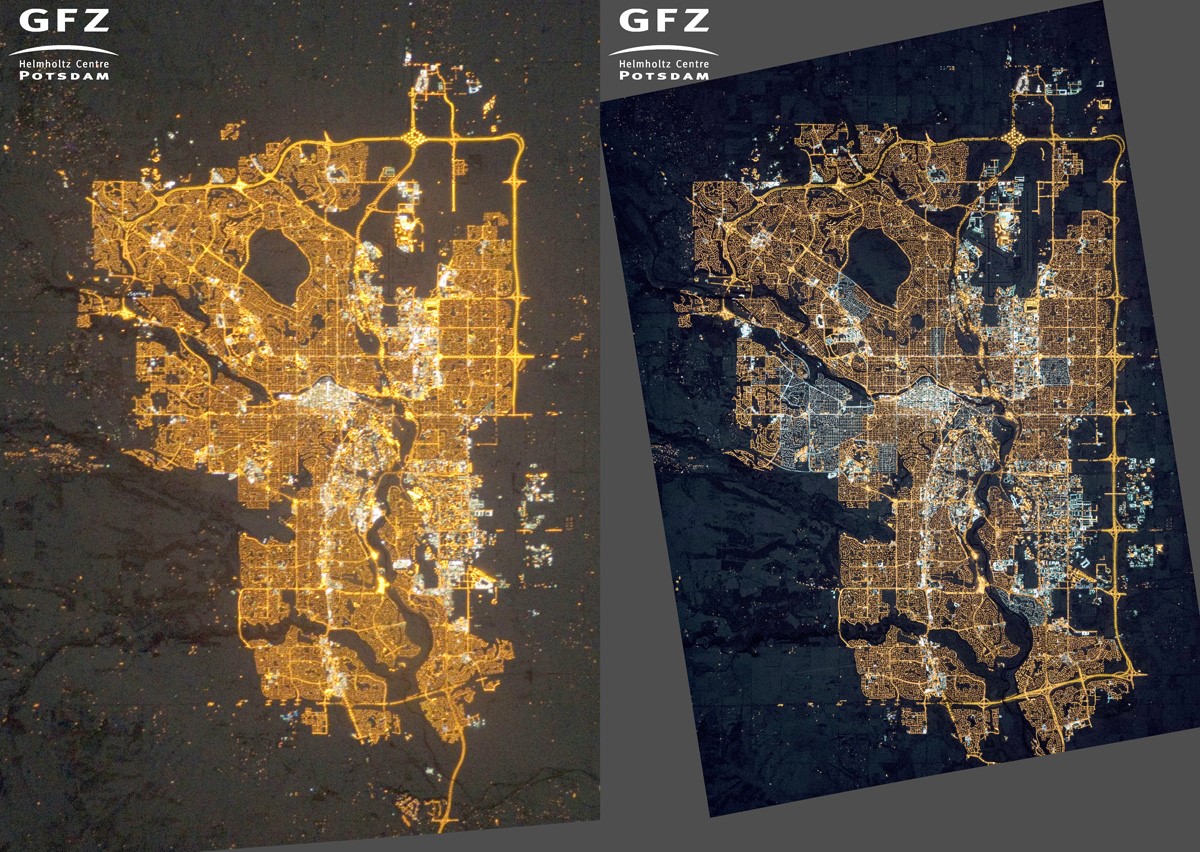

Using data from an Earth-observing weather satellite called Suomi NPP, the new study shows that between 2012 and 2016, artificially lit regions on Earth increased in brightness by 2.2 percent. In addition, the total area where artificial lighting appeared also increased by 2.2 percent, providing an illustration of humanity's expansion into previously undeveloped areas.

When broken down by country, the results show that in many developing nations, the increases in artificial lighting are well above the global average, as more people gain access to electricity and outdoor lighting equipment for highways, city centers and residential areas. [Photos: Light Pollution Around the World]

Article continues belowBut even in many developed nations, the output of artificial light may be increasing as well, despite some regional efforts to curb it, the study shows. Light pollution has many side effects, including disrupting the circadian rhythms of plants, animals and humans.

The view from space

The data for the new study comes from the Suomi NPP satellite, which was designed as an operational testbed for critical hardware components that will go on a next-generation series of weather satellites from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The first of those satellites launched into space this month. The new additions will help meteorologists develop seven-day forecasts, as well as manage things like wildfire tracking and management, monitoring of storms and natural disasters, disaster relief efforts and a slew of other applications.

One of the instruments aboard Suomi NPP is called the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite, which includes a sensor called the Day/Night Band (DNB). The DNB was designed to provide high-resolution images of clouds at night to assist in weather forecasting, according to Christopher Elvidge, a physical scientist at NOAA who spoke at a telephone news conference held yesterday (Nov. 21).

Suomi NPP orbits the globe from pole to pole, while the planet spins underneath it, so that it captures a view of the entire planet about twice per day. It has a "footprint" of 750 meters square, which means that's about how large each pixel is on the VIIRS images.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The way that I characterize it often is that the [VIIRS] day-night band allows us to work kind of at the neighborhood level," Christopher Kyba, a postdoctoral researcher at the German Research Centre for Geosciences and lead author on the new paper, said during the news conference.

The observations showed a decrease in lighting usage in a few places, including Syria and Yemen, which have both been undergoing intense warfare. The paper notes that "with few exceptions, growth in lighting occurred throughout South America, Africa, and Asia."

Blue light

The study has an important caveat that is introduced by the VIIRS instrument: The data that the study was based on did not include all wavelengths of light that are visible to the human eye. Specifically, the data does not include "blue" light. Traditional light bulbs (like sodium lamps and most halogen lights) emit mainly in yellow, orange and red wavelengths of light, but many LED light bulbs emit high levels of blue light.

As a result, the total increase in light pollution visible to the human eye is actually higher than what's reported in the paper, the researchers said. And, while some cities may appear to reduce their light output year after year in the data, those cities may just be switching over to LEDs; the apparent reduction is simply a shift of the light into the blue wavelength, they said. In an email to Space.com, Kyba said it would be extremely difficult to try and estimate how much blue light each country emits, because that varies widely among all kinds of light bulbs.

The authors noted that photographs of the Earth taken from the International Space Station provide a means of seeing the full spectrum of light pollution from space. In the study, they compared those images to the Suomi NPP satellite data to provide "color information ... that can help us to understand, at least for specific cities, where the lights are changing color," Kyba said. Milan, for example, switched many of its yellow-light sodium lamps to white-light LEDs, and that change is visible in ISS images, he said.

While LEDs can in some cases help to reduce light pollution, the increased use of LEDs also leads to something called the "rebound effect," Kyba said. As LED lights become more efficient and cheaper, people tend to use them more, rather than holding on to the energy savings.

Kyba compared it to a person buying a hybrid car to reduce his or her carbon footprint, but then ultimately feeling free to drive more because of that decision, and in the end producing the same level of carbon emissions that the individual would have created with a regular car.

So while the study suggests that many large cities may be stabilized in their light output (because they aren't adding any major new sources of artificial light), that stabilization may be offset by nearby, smaller cities that are adding more lights to roads and parking lots that were previously unlit, Kyba said.

The need for night

"The biological world is organized, to a large extent, by natural cycles of variation in light," Franz Hölker, a scientist at the Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries and a co-author on the study, said during the teleconference. "And this variation triggers a wide range of processes, from gene expression to ecosystem functions."

Artificial light, and the subsequent loss of nighttime darkness, is "a very new stressor" that many organisms have not had time to adapt to, according to Hölker. Thirty percent of vertebrates and more than 60 percent of invertebrates are nocturnal, he said, so artificial lighting can directly affect the life and sleep cycles of those organisms, and there have been many studies documenting this phenomenon.

That can also have a ripple effect on the ecosystem, he said. For example, a recent study showed how street lamps affect insects that pollinate plants at night, thus impacting the plants as well.

"[Light pollution] threatens biodiversity through changed night habits, such as reproduction or migration patterns, of many different species: insects, amphibians, fish, birds, bats and other animals," Hölker said. "And it can even disrupt plants by causing … late leaf loss and extended growing periods, which could of course impact the composition of the floral community."

High levels of artificial light may also impact health in humans by reducing the body's production of melatonin, a hormone that can affect things like the body's immune system, mental health and fertility. It also reduces people's ability to see stars and celestial objects, which astronomers and social scientists argue has a negative impact on culture and science. It's estimated that about one-third of the world's population cannot see the band of the Milky Way galaxy at night, due to light pollution. That includes 80 percent of people living in North America.

The researchers said they hope their research can be used in efforts to initiate policy changes that combat light pollution. Kyba is involved with the International Dark-Sky Association, which is taking steps to fight this problem.

The paper appears today (Nov. 22) in the journal Science Advances.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield.Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter