Farewell, Cassini: Gorgeous Final Photos Are a Fitting Send-Off for Saturn Probe

The Cassini spacecraft's farewell images are jaw-dropping, just like countless other photos the probe snapped during its 13 years in the Saturn system.

Cassini's historic mission came to a dramatic end today (Sept. 15), with a deliberate plunge into Saturn's thick atmosphere. As it zoomed toward the ringed planet Wednesday and Thursday (Sept. 13 and 14), the orbiter took a series of photos, a handful of which Cassini team members processed and released as a sort of tribute, and as a service to space fans around the world.

"My imaging team members and I were especially blessed to serve as the documentarians of this historic epoch and return a stirring visual record of our travels around Saturn," Cassini imaging team leader Carolyn Porco, of the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado, said in a statement. "This is our gift to the citizens of planet Earth." [In Photos: Cassini's Last Views of Saturn at Mission's End]

One of these gifts is a short movie of the icy Saturn moon Enceladus setting behind the gas giant.

Cassini's narrow-angle camera captured the images that make up the movie over the course of about 40 minutes on Wednesday. At the time, Cassini was about 810,000 miles (1.3 million kilometers) from Enceladus and about 620,000 miles (1 million km) from Saturn, imaging team members wrote.

It's fitting that some of Cassini's final images depict Enceladus, because the spacecraft made some of its biggest discoveries about the moon. In 2005, Cassini spotted geysers blasting from Enceladus' southern reaches, and when the spacecraft passed through the spray, it detected water and carbon-containing organic compounds.

Cassini scientists later determined that this material is coming from a big underground ocean, which appears to be capable of supporting microbial life. Indeed, the main reason the Cassini team sent the probe on its suicide plunge today was to ensure that the orbiter would not contaminate Enceladus (or fellow Saturn moon Titan, which also may be habitable) with microbes from Earth.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

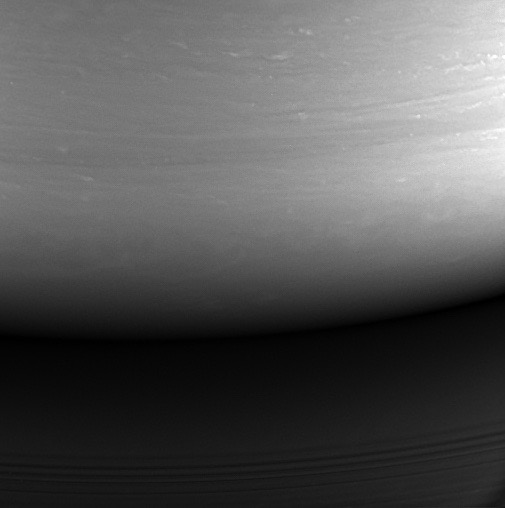

Cassini also photographed its grave site hours before making its fatal descent into those Saturnian clouds.

This Sept. 14 image of Saturn's atmosphere is a composite. It shows a monochrome view from the probe's wide-angle camera; a natural-color view of the same scene was also created using the Cassini imaging system's colored spectral filters.

The clouds are lit by the light reflected off Saturn's rings, according to NASA. This area of Saturn was actually on the nightside of the planet when photographed, but it had rotated into daylight by the time Cassini met its fiery end there. Cassini's wide-angle camera captured the image at a distance of just 394,000 miles (634,000 km) from Saturn.

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a partnership among NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency. (Huygens was a piggyback European lander that touched down on Titan in January 2005.) The Cassini orbiter was designed and assembled at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and its imaging team includes scientists from the United States, England, France and Germany.

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.