Carbondale, Illinois Prepares to Broadcast 2017 Solar Eclipse Nationally

The city of Carbondale, Illinois has a population of 26,324, but on Aug. 21, 2017, the Midwestern college campus at the heart of the city will transform into something closer to New York's Times Square on New Year's Eve. Organizers are expecting about 45,000 people to be in attendance to watch the total solar eclipse, in one of the most breathtaking cosmic events that can be seen with the naked eye.

In Saluki Stadium at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, the school and the city will host an eclipse program featuring speakers, videos about eclipse science and safety, and feeds from other locations along the eclipse path. There will also be multiple cameras pointed at the sun during the partial eclipse (when the moon is only partially covering the sun) and then during the 2 minutes and 40 seconds of totality.

During that brief period, when the sun will be completely covered by the moon, the world will be dipped in a midday twilight, the streaming jets of gas that make up the sun's atmosphere will become visible, and the horizon will take on the color of a sunset. A total solar eclipse is considered by avid skywatchers to be one of the most amazing natural phenomena that can be viewed with the naked eye. Carbondale is only a few miles from the point of "greatest duration" on the eclipse path, meaning totality will last longer there than anywhere else, according to NASA. It's a difference of seconds, but for such a rare event, that can mean a lot. [How to Safely Watch The 2017 Total Solar Eclipse]

The broadcast from Saluki Stadium will be part of NASA TV's live coverage of the event, and it will also be made available on the web and to all PBS stations. Some of the isolated footage of the eclipse will be made available to other TV stations. The cameras pointed at the sun will capture a low-resolution view that will be best for live shots, and multiple high-resolution shots that will later be combined (or stacked) to create something closer to what the human eye can see during a total eclipse.

"Unfortunately, not everyone can get to the path of totality. We know we're not going to get them all," Mike Kentrianakis, project manager for the American Astronomical Society's Solar Eclipse Task Force, told Space.com. "But the secondary thing they can do, is see it on TV."

Practice, practice, practice

Kentrianakis spent 20 years working for the CBS Television Network, and he's seen 10 total solar eclipses. He shared that combined expertise with the local Carbondale event organizers and NASA representatives during a meeting earlier in May, when the group hashed out the program schedule for Aug. 21.

"I'm very aware of time [during a total eclipse], and what happens, and how people feel," he said. "I suggested to them that, for example, this thing should be moved up because it's related to this, and then this thing is going to be happening in Oregon, and then we're getting closer to totality."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Timing is everything when it comes to a total solar eclipse. Totality lasts less than 3 minutes, and it will not wait for cameras to be focused or speeches to be finished. If the broadcast feed isn't set up right or the cameras aren't correctly focused, or if some other critical detail slips through the cracks, there is no redo; at least not until the next total solar eclipse passes over Carbondale in 2024.

"You get one shot!" Kentrianakis said. "Everything has to be in focus, and the directors have to know what they're doing; it can be nerve-wracking. This could be very difficult live television."

The moon's shadow is roughly circular and, on average, about 70 miles wide. It will move across the country at about 1,251 mph (2,013 km/h). The Carbondale program will be interspersed with shots of totality from other locations inside the path, and will culminate when the shadow reaches this corner of southern Illinois.

"They've got the program jam-packed with stuff," Kentrianakis said. "There's not going to be any dead air time whatsoever. This is going to be a very fast-moving event. Very."

NASA Edge, a podcast produced by a group inside NASA, has also chosen Carbondale as its headquarters. The NASA Edge team is working with Kentrianakis and the local team to do its own broadcast from a constructed studio just outside the stadium.

The organizers and the broadcast team will hold additional dress rehearsals for the Saluki Stadium starting Aug. 15. A tech team will take care of the significant amount of audio-visual equipment involved in this production. They will need to connect the multiple broadcast locations (including team members walking around the crowd with cameras), and get the signal out to NASA TV's eclipse headquarters in Charleston, South Carolina, as well as to the PBS stations, which will also require the help of the local TV station, WSIU. [Total Solar Eclipse Visible From United States In 2017 | Visualization]

The equipment necessary to image the sun through a telescope in high resolution isn't cheap or easy to put together, so NASA is having a "solar lab" constructed by a company called Lunt Solar Systems in Tucson, Arizona. The solar lab will include a heliostat, which reflects the sun's image toward a camera or telescope. This is so the cameras and telescopes don't have to keep turning as the sun moves across the sky. Two of the telescopes will be set up to observe the sun using a technique that captures light in a very narrow wavelength range, instead of the entire wide spectrum of wavelengths the sun emits. (These wavelengths are known as hydrogen alpha and Calcium-K.) Looking at the star in select wavelengths reveals structures and textures that are typically invisible.

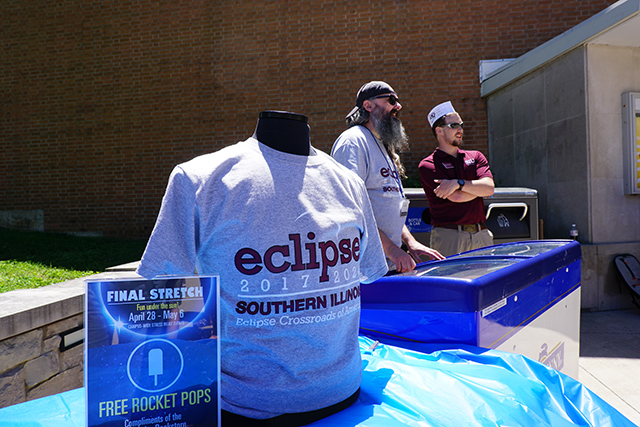

Carbondale has been preparing for the total solar eclipse event for more than three years, according to Bob Baer, the leading organizer for Carbondale's eclipse events and an employee of Southern Illinois University, and the city has pulled out all the stops. The five days leading up to the eclipse will be filled with events, including a carnival, a Comic-Con, an arts and crafts fair, a science and technology expo and space science activities at the nearby Adler Planetarium. In addition, there will be talks, panel discussions and activities that relate to the eclipse.

"Bob has a lot on his plate and he doesn't want to see anything fail," Kentrianakis said. "But we have the backup feeds — it's going to happen. A long as we get on the air and we have a satellite connection, it's going to be a wonderful show. I have a lot of confidence."

What's all the fuss about?

The last total solar eclipse visible in the U.S. appeared over Hawaii in 1991; another eclipse crossed a few small islands in Alaska in 1990. But those places aren't accessible for most of the population, and the last total solar eclipse in the continental U.S. took place in 19799 — it quickly swooped through Washington state and Montana before moving into Canada. In 1970, an eclipse moved up the Eastern Seaboard, but according to Kentrianakis, clouds blocked the view for many people who came out to see it. The eclipse before that, in 1963, was visible only in Alaska and Maine. The last eclipse to cross the entire continental U.S. was in 1918.

"Eclipses are just so lost in American memory," Kentrianakis said. Despite having seen 10 total solar eclipses elsewhere in the world, he's never seen one in the U.S.

While total solar eclipses happen about every 18 months, they're visible from only a very small strip of Earth. "Eclipse chasers" like Kentrianakis travel the world to catch those few breathtaking moments.

The rarity of a total solar eclipse being easily accessible to such a huge portion of the U.S. population is why the AAS has been planning its public-outreach strategy for over two years. It's why NASA's eclipse outreach now involves hundreds of people, including agency staff members, various contractors and partners, according to Alex C. Young, a solar physicist at NASA's Goddard Spaceflight Center, who is leading the agency's eclipse outreach effort. It's why cities like Carbondale, and others in the path of totality, are planning to welcome massive crowds, and bracing for the onslaught.

"Americans have not had a chance like this to engage in cosmic awareness since the launching of Apollo 11 in 1969. That's what this is like," Kentrianakis said. "We need to educate [Americans] and excite them and get them enthusiastic. When they see this event, they will know that we were not at all underestimating the beauty of this."

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter