Mission to Venus: NASA and Russia May Explore Hellish Planet Together

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

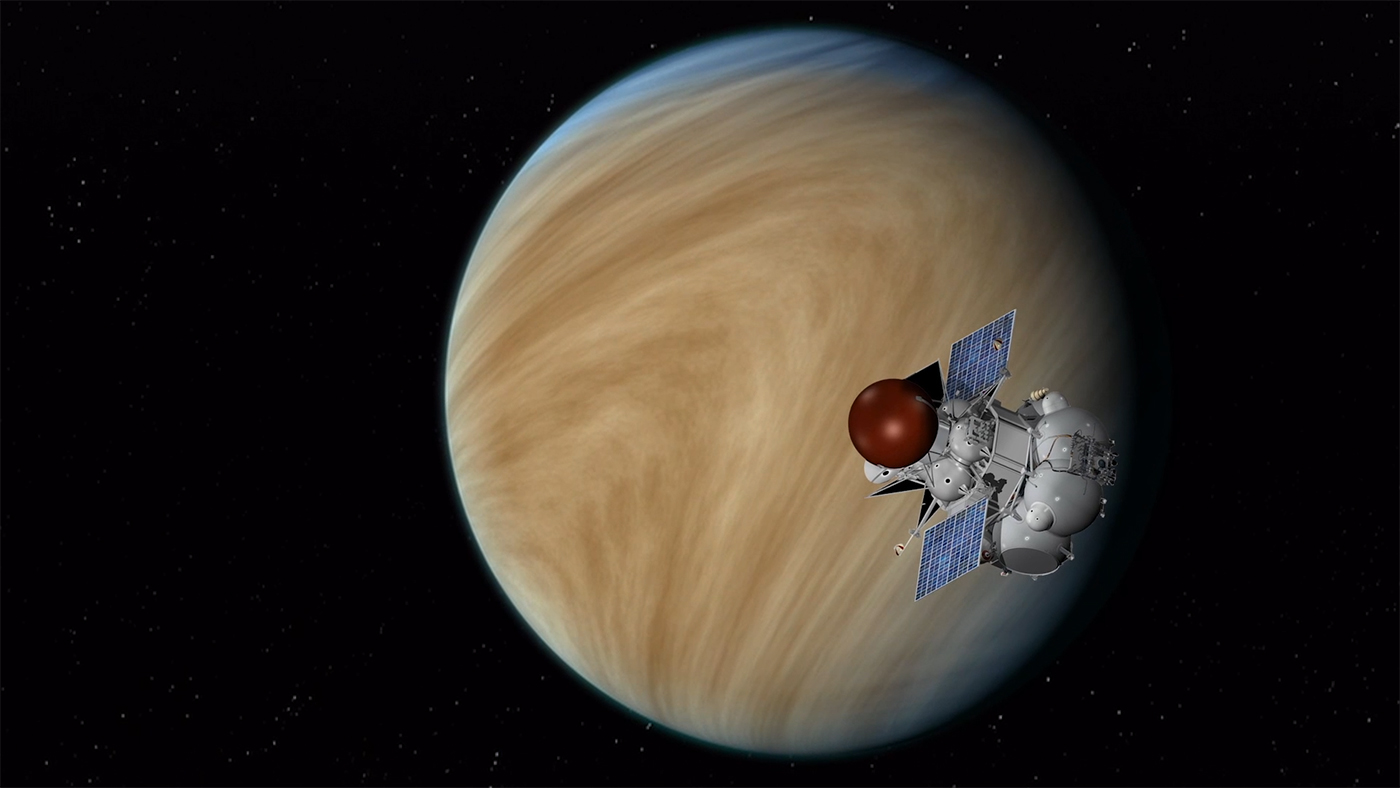

NASA scientists are meeting with representatives from the Russian Academy of Sciences' Space Research Institute (IKI) this week, to continue discussion of a possible collaboration on the institute's upcoming Venera-D mission to Venus, NASA officials announced last week.

Russia launched 16 space probes toward Venus as part of the Venera series between 1961 and 1983, including the only probes to ever successfully land on the surface of hellish planet. The IKI Venera-D mission is scheduled to launch sometime in the 2020s. The mission would include an orbiter and a lander, and possibly a solar-powered airship that would fly through Venus' upper atmosphere.

"This potential collaboration makes for an enriching partnership to maximize the science results from Venera-D, and continue the exploration of this key planet in our solar system," Adriana Ocampo, who leads the Joint Science Definition Team working on a report regarding the potential partnership, said in the statement. [Photos: Venus, the Mysterious Planet Next Door]

Scientists from NASA will meet with representatives from IKI to "[identify] shared science objectives for Venus exploration," according to a statement from the agency.

Earth and Venus share many similarities — such as their size, composition and proximity to the sun — and yet Venus' atmosphere has experienced a runaway greenhouse effect that generates surface temperatures hot enough to melt lead. Venus is hotter than Mercury, even though the latter is closer to the sun.

NASA has sent multiple probes to study Venus from orbit, beginning with the Mariner 2 orbiter in 1962. The U.S. space agency's last dedicated Venus mission was Magellan, which launched in 1990 and mapped 98 percent of the planet's surface over four years.

"While Venus is known as our 'sister planet,' we have much to learn, including whether it may have once had oceans and harbored life," Jim Green, director of NASA's Planetary Science Division, said in the statement. "By understanding the processes at work at Venus and Mars, we will have a more complete picture about how terrestrial planets evolve over time and obtain insight into the Earth’s past, present and future."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter