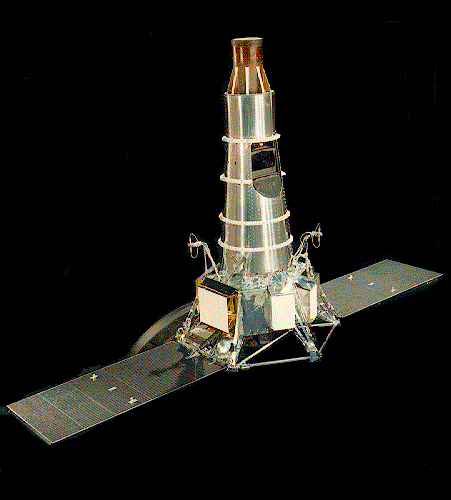

Ranger 7: First U.S. Close-Ups of the Moon

Ranger 7 was the first American spacecraft to image the moon's surface from close-up. Along with Rangers 8 and 9, its pictures helped the United States plan the excursions for the Apollo program, which saw astronauts land on the moon between 1969 and 1972.

The spacecraft came at a very early time in space exploration, when engineers were still learning the fundamentals about how to keep a machine working in space. As such, Ranger 7 followed six failed missions in its own program over several years. It made the first pictures extra-special.

Failure

NASA was tasked with sending astronauts to the moon in 1961, when the agency had accumulated just 15 minutes of human spaceflight experience. It spent the next decade building the rockets and spacecraft needed for the journey, and training the astronauts across three programs (Mercury, Gemini and Apollo). This culminated with the first human landing on the moon on July 20, 1969.

But before humans could go there, scientists needed to know what the surface looked like. Even telescopic views of the moon indicated lots of craters, and at least the first missions would be safest on flat ground. Some scientists also were unsure how much dust was on the surface; a few even thought an unwitting crew could sink into the dust upon landing (which turned out not to be the case.)

The first Ranger spacecraft launched on August 23, 1961. While the launch went well, the Agena rocket stage failed to put the spacecraft in the right orbit around the Earth. Ranger 1 eventually ran out of gas, and its solar powers failed to track the sun, putting the probe on battery power until it died on Aug. 27.

Only a handful of satellites had gone into space at this time, however. The urgency was that the Soviet Union and the United States were both engaged in a race to send people to the moon for national pride purposes, as well as to demonstrate which political system (communism or democracy) was more capable of taking on large challenges. In fact, in 1959 the Soviet Union sent two successful missions to the moon, including Luna 3, the first to take pictures of the far side of the moon.

NASA continued suffering several failures with the Ranger program and other moon-bound probes (including several consecutive failures in the Pioneer program). Ranger 2 failed to leave Earth orbit. Ranger 3 got out of Earth orbit, but missed its target. Ranger 4 did hit the moon, but it didn't send back any data during its journey there due to a computer failure. Ranger 5 missed the moon completely; Ranger 6 hit the moon, but also didn't send back any pictures. By the time Ranger 7 launched in 1964, NASA had sent 12 missions to the moon and had still not achieved its main objective of taking pictures.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Recovery

It should be emphasized that NASA tried engineering fix after engineering fix to resolve the problems, including a lengthy examination into the camera problems plaguing Ranger 6. Tensions mounted when contractor RCA found a polyethelene bag inside a sealed electronic module on Ranger 7's television subsystem, containing 14 screws and a lock washer, according to "Lunar Impact: A History of Project Ranger," a NASA history book on the mission. While the initial suspicion was sabotage, interviews were performed and it was later determined that somebody placed it there out of fatigue and overwork. The launch proceeded as planned.

A lengthy investigation into Ranger 6's camera failure turned up several dead ends until Alexander Bratenahl, a physicist with the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, looked at films of Atlas launches and focused on the gas plumes produced after the rocket went through staging. The gas likely caused an electrical short in the camera's power supply after it got through the (loosely held) umbilical door on the payload shroud, which contained the camera.

Both the electrical system and camera were therefore modified for Ranger 7's launch. NASA also stepped up its testing procedures in general for Ranger 7, including a "buy-off committee" that reviewed all of Ranger 7's systems shortly before launch to make sure that it was flight-ready.

The first launch attempt on July 27, 1964, did not go forward due to a ground equipment malfunction, but the next try on July 28 went perfectly. "At 1:20 pm, over the West Coast of South Africa, the Agena engine fired again, injecting the spacecraft onto its lunar trajectory," the NASA book stated. "The deep space station at Johannesburg reported separation of the spacecraft from its carrier rocket: Ranger 7 was on its way to the moon." JPL reported a 50-50 chance of success to eager reporters.

A midcourse correction was performed on July 29, and at that time the television system appeared to be working. Ranger 7 slammed into the moon's Mare Cognitum region as planned that evening as controllers cheered. Film footage from the camera (which was transmitted to Goldstone, Calif.) required processing before the scientists could look at them, which took a couple of days.

On July 31, JPL scientists finally had their hands on the pictures, which (though primitive by today's standards) showed high-resolution views of craters and other features on the moon. At an evening press conference, reporters asked if the pictures showed it was safe enough for Apollo astronauts to walk on the surface, according to the NASA book.

"Many more days of analysis remained before any formal conclusions would be advanced," the book stated, adding, "All of the experimenters present were impressed by the continuity of features from the large craters observable with telescopes down to smaller and smaller ones."

Further pictures taken with Rangers 8 and 9, along with landings from the Surveyor program, helped scientists confirm it would be safe to send astronauts to the surface. Twelve astronauts made the journey to the surface. While the Apollo program ceased in 1972, lunar missions have continued through the decades, with more recent missions finding evidence of ice in permanently shadowed craters, and investigating reports of dust levitation at the sunrise-sunset line on the moon.

Additional resource

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.