Crashing Comets Create Dusty Stellar Death Shroud

A swarm of colliding comets is weaving a dusty death shroud for a distant stellar corpse and providing astronomers with rare proof that certain solar system objects can outlive their suns.

Video: Comets: Bright Tails, Black Hearts

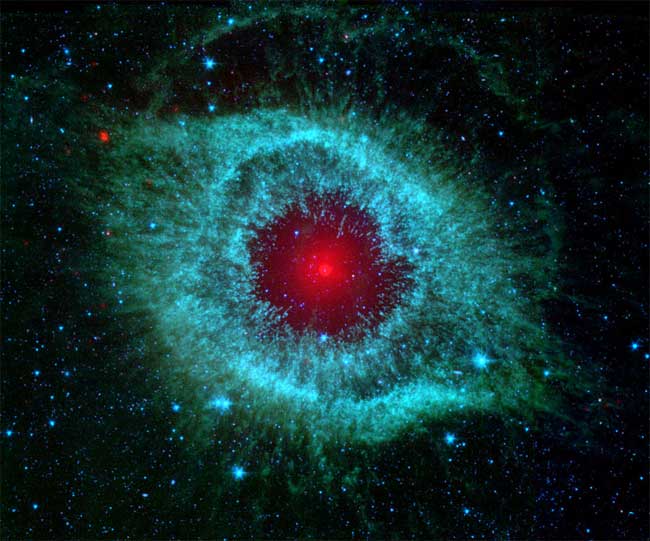

Using NASA's Spitzer space telescope, astronomers spotted a cloud of gas and dust surrounding a dead star, called a white dwarf, in the Helix nebula, located 700-light-years away in the constellation Aquarius.

"We were surprised to see so much dust around this star," said study team member Kate Su of the University of Arizona. "The dust must be coming from comets that survived the death of their sun."

The white dwarf was formed when a star much like our Sun died and cast off its outer layers. Radiation from the white dwarf's still-hot core heated the expelled material, causing it to glow in vivid colors.

The result is an enormous, colorful structure that looks eerily like a giant eye peering out maliciously across the heavens [image].

A dusty surprise

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Astronomers have long studied the white dwarf at the center of the Helix nebula, but dust had never been detected until now. Using Spitzer's infrared eyes, Su and her team spotted a dusty disk circling the dead star at a distance of about 35 to 150 AU. (One AU is the distance between our Sun and Earth.)

The existence of the dusty disk was a surprise. Astronomers had thought the star had blown away all of the dust in its system when it died and cast off its outer shells.

The astronomers therefore think the disk was formed from dust flung about during comet collisions. Recent close-up observations of comets from missions like Deep Impact have confirmed they are giant balls of ice, dust and rock particles bound together by gravity.

A star like ours

The Helix nebula's white dwarf was likely once a lively star like our Sun, surrounded by a cosmic entourage of comets, asteroids and possibly even planets, the astronomers reason.

When the star died, it first went through a red giant phase, swelling to a colossal size and engulfing its inner planets (Earth will one day meet a similar fate). Outer worlds, asteroids and comets would have survived, but their once-neat orbits would have been thrown out of whack, putting some of them on collision courses with one another.

As part of its final death throes, the bloated, dying star expelled its outer layers, until only a small, dense and relatively cool core-the white dwarf-remained. Meanwhile, the messy comet collisions occurring at the outer fringes of the solar system continued.

A mystery solved?

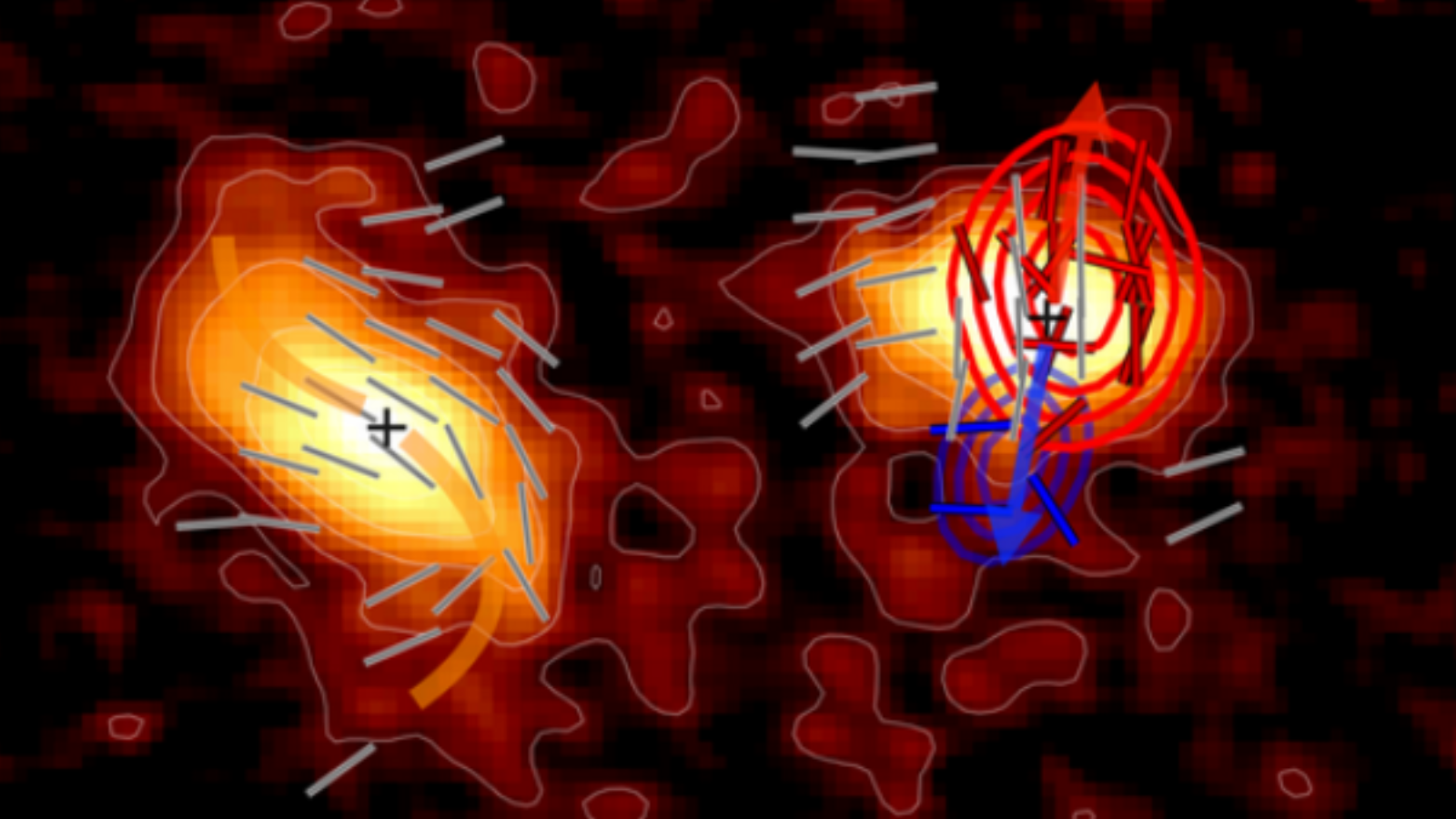

The findings are rare proof that objects like planets, comets and asteroids can survive the death of their stars. In January of last year, astronomers using Spitzer also spotted a debris disk surrounding a distant white dwarf called G29-38 [image]. However, that disk was much smaller and located closer to its star.

The findings could also help explain a mystery surrounding the Helix nebula's white dwarf. Previous observations showed that the dead star was emitting highly energetic X-rays-something that a cooling, dead star should not do.

But if comets and other objects are colliding helter skelter into one another around the white dwarf, as the new observations suggest, then some of them might fall onto the dead star and trigger X-ray outbursts.

"The high-energy X-rays were an unsolved mystery," said study team member You-Hua Chu of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. "Now, we might have found an answer in the infrared."

- Top 10 Star Mysteries

- Video: SL9: The Comet That Changed Comet-Hunting

- Naked White Dwarf Shows its Dead Stellar Engine

- Deep Impact Poised to Crack Comet Mysteries

- White Dwarf Hints at Our Solar System's End

Ker Than is a science writer and children's book author who joined Space.com as a Staff Writer from 2005 to 2007. Ker covered astronomy and human spaceflight while at Space.com, including space shuttle launches, and has authored three science books for kids about earthquakes, stars and black holes. Ker's work has also appeared in National Geographic, Nature News, New Scientist and Sky & Telescope, among others. He earned a bachelor's degree in biology from UC Irvine and a master's degree in science journalism from New York University. Ker is currently the Director of Science Communications at Stanford University.