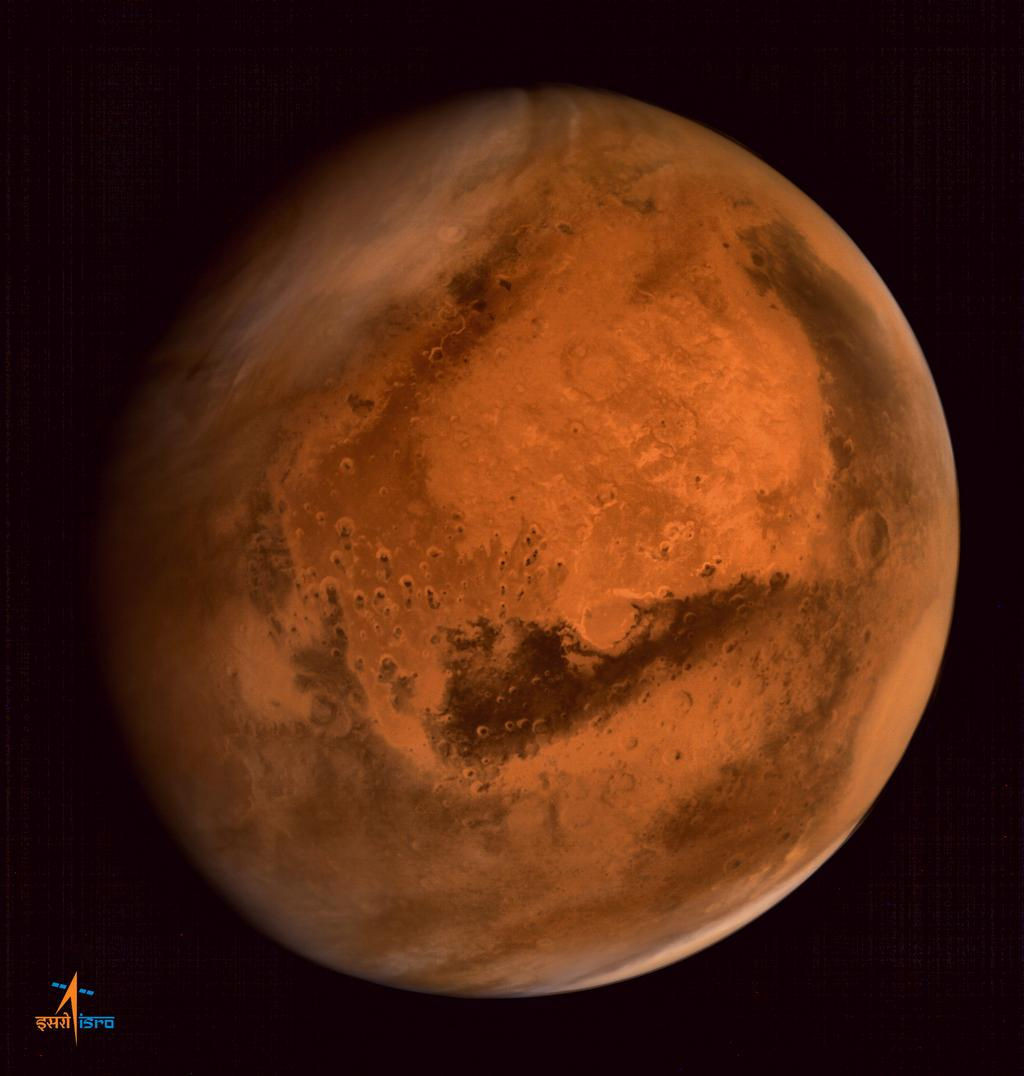

Follow the Salt: Search for Mars Life May Focus on Driest Regions

If life ever existed on Mars, its last outposts near the Red Planet's surface might have been in very salty environments, new research shows.

This premise might help guide where future rovers land to look for signs of past or present Mars life, scientists say.

The idea that Mars may have once hosted life is rooted in plentiful evidence suggesting that rivers, lakes and seas covered the Red Planet billions of years ago. Because there is life virtually everywhere there is liquid water on Earth, some researchers have suggested that life might have evolved on Mars when it was wet, and that life could perhaps survive on the planet even now. [The Search for Life on Mars: A Photo Timeline]

Currently, the search for signs of possible life on Mars is mostly focused on ancient wet habitats. However, researchers now suggest that future missions to Mars might also want to consider drier places that past Martian life might have inhabited.

Although Mars might once have possessed lots of water on its surface, it dried over time, and is now an extremely arid planet. In the new study, scientists reason that ancient Martian microbes might have colonized the land just as life did on Earth, and then adapted to the Red Planet's increasing aridity.

To reconstruct how ancient Martian life might have evolved to survive the drying of Mars, scientists investigated adaptations to aridity on Earth. They found that "there is a predictable sequence of how organisms adapt to increasing dryness," said study co-author Dirk Schulze-Makuch, an astrobiologist at Washington State University in Pullman.

In Earth's arid regions, many organisms can dry up without dying and can resume life quickly after rehydration, even after years of complete desiccation. Biological soil crusts made of relatively complex communities of microbes can cover up to 70 percent of the surfaces of some deserts, the researchers said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

However, a dramatic change is seen when a region shifts from arid to hyperarid. Biological soil crusts become increasingly fragmented or patchy, and there is a significant decline in microbes' abundance and diversity. Instead, microbes in hyperarid areas are usually lithobiontic — that is, they colonize either the surface, underside or interior of rocks, the researchers said.

In the driest regions of the Earth, relatively complex and abundant communities of microbes can still survive inside porous crusts made of salt. These crusts are hygroscopic — in other words, they tend to absorb moisture directly from the air, the researchers said.

The researchers suggested that, as Mars dried, microbes eventually might have evolved to subsist on atmospheric moisture. Liquid brines within salt crusts might have served as the last available habitats for life near the Martian surface, Schulze-Makuch said.

"The last near-surface life on Mars would most likely be associated with salts," Schulze-Makuch told Space.com.

The scientists suggested that these refuges may have disappeared only recently — or may still exist. As such, future missions to Mars may want to analyze salty rocks, he said.

Schulze-Makuch noted that it's also possible that life survived deep underground on Mars, "such as within lava-tube caves."

Schulze-Makuch and his colleague Alfonso Davila at the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute in Mountain View, California, detailed their findings online Feb. 2 in the journal Astrobiology.

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us