NASA Picks Tiny Satellites to Ride on Giant Rocket's 1st Flight

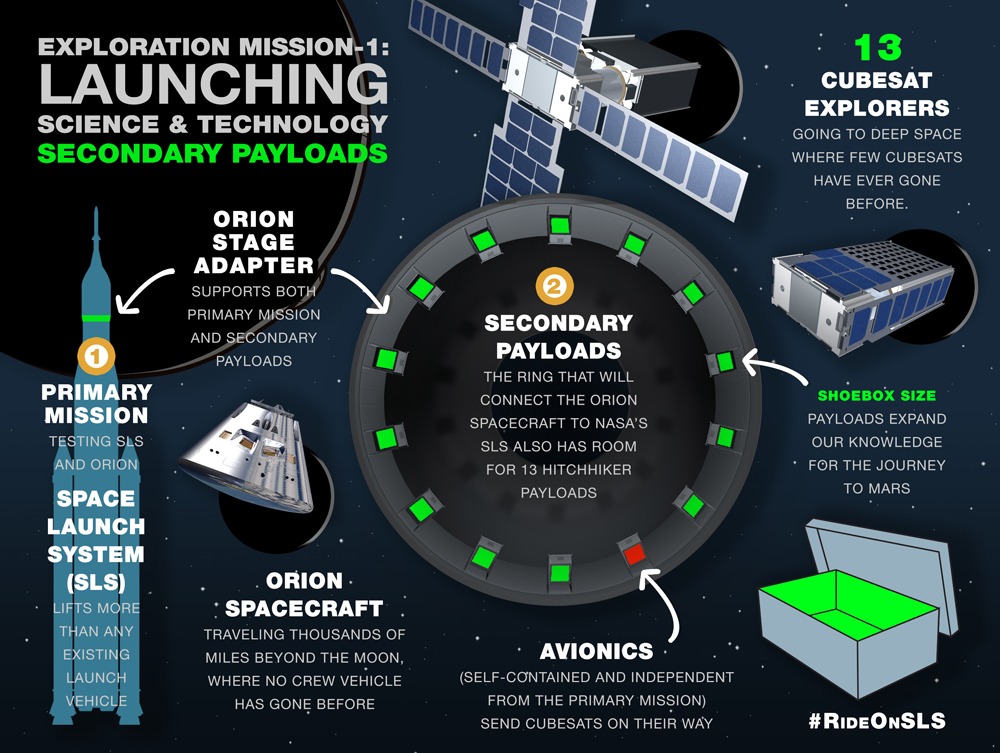

NASA has unveiled the lineup of 13 small satellites that will hitchhike on the first deep-space test flight of its new megarocket, a list that includes satellites destined to probe the moon, investigate deep space radiation and even fly out to examine an asteroid.

While the microsatellites, called cubesats, have been deployed into orbits close to Earth before, and launched from the International Space Station, the low-cost research units have never before ventured this far away to do research, NASA officials said from the Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama. The agency's huge rocket under development, the Space Launch System (SLS), will carry the microsatellites the extra distance in its first full test launch in 2018.

"This is unprecedented: to take a cubesat-class payload thousands of miles away from the Earth, out into deep space, and to actually conduct science," Chris Crumbly, manager of the Space Launch System spacecraft and Payload Integration/Evolution Office at Marshall, said in a news conference today (Feb. 2). [NASA's Space Launch System Mega-Rocket in Pictures]

The SLS rocket is designed to ultimately carry humans into deep space aboard an Orion spacecraft. NASA has been steadily testing parts of the system; all seven of the engine tests were completed in 2015, and progress has been made on solid rocket booster tests and the huge Vertical Assembly Center. When complete, the rocket will be 323 feet (98.5 meters) tall, and although it's slightly shorter than the Saturn V rocket that propelled humans to the moon, it will have 23 percent more thrust, Crumbly said.

The first test flight won't carry humans aboard, but there will be other passengers: the 5-foot-wide (1.5 m), 18-foot-diameter (5.5 m) hoop that connects the rocket to the Orion spacecraft will have room for 13 little cubesats attached to its inner wall. NASA officials had revealed at least three of the cubesats to ride on the Space Launch System before, but Tuesday's announcement confirmed the total number and added several to the list.

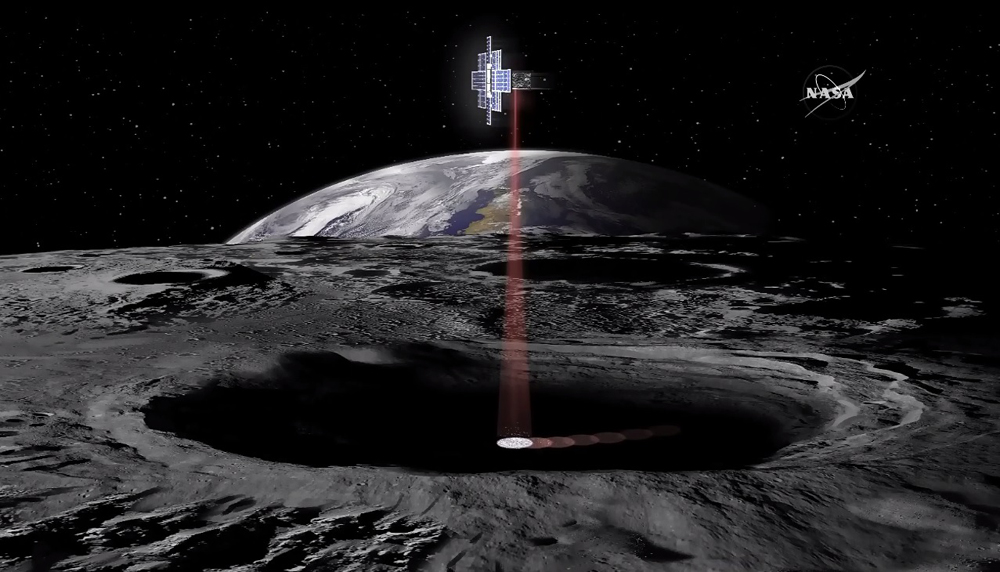

Four of the cubesats will examine various aspects of the moon up close, investigating the surface and hunting for ice deposits and good locations to extract resources. A "space weather station" will measure particles and magnetic fields in space for a potential space-weather-monitoring network, and another cubesat will measure deep-space radiation's impact on yeast over the course of 18 months, to understand organisms' reaction to the deep-space environment over time — one of the biggest challenges to long-duration spaceflight, NASA officials said.

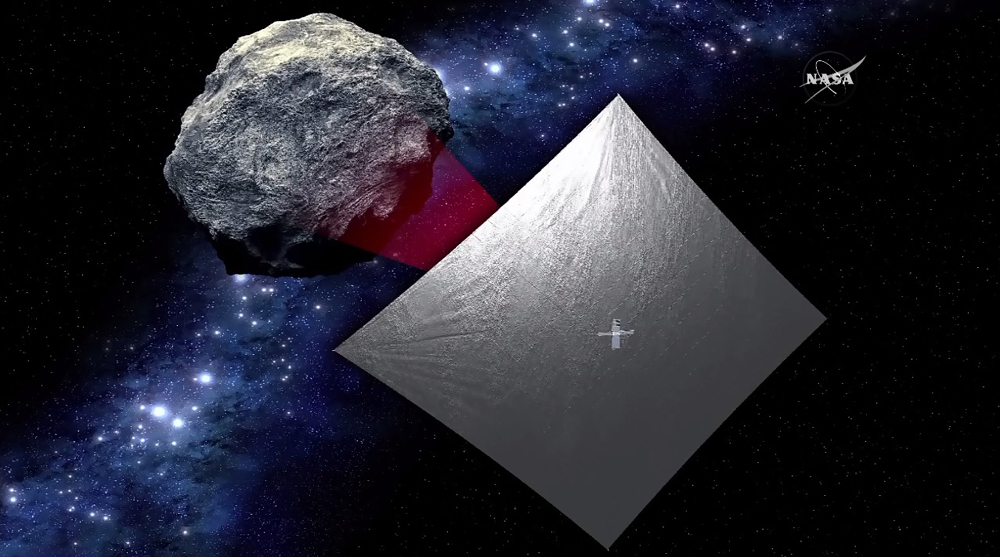

Another cubesat will travel out to the small asteroid 1991VG under the power of a solar sail. The 86-square-meter (926 square feet) sail will be the thickness of a human hair. It will be pushed by the pressure of sunlight reflecting off of it, driving the craft forward and ultimately past the asteroid, slowly enough to image most of its surface as it rotates.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The sail, plus solar panels, a processor, a camera and other observing tools, will all begin the journey folded into a volume the size of a shoebox and weighing no more than 30 lbs. (14 kilograms) — "the most complicated game of Tetris you've ever played," said Leslie McNutt, project manager for the cubesat, called the Near-Earth Asteroid Scout. Similar craft could inexpensively survey asteroids to prepare for human visits.

Three more of the cubesat slots will be filled by winners of NASA's Cube Quest Challenge, a contest that is open to any nongovernment team and that will conclude in 2017. The three cubesats selected will actually continue to compete in space, winning shares of the prize if they end up in orbit, and competing in a "Deep Space Derby" or "Lunar Derby" to complete additional research tasks.

The final three cubesats will be chosen from among international partners and will be announced later, NASA officials said — but like the other cubesats, their research will complement NASA's ultimate goals of human exploration, the officials added.

All 13 cubesats will be released into space after SLS launches the Orion craft into a stable orbit past the moon and Orion reaches a safe distance from the rocket's upper stage. The science will be an added bonus to the test flight's main achievement: proving SLS and Orion's capability to support human missions into deep space, and eventually to Mars, the researchers said.

"SLS and the Orion spacecraft are going to take people further than we've ever taken people in human history," Dava Newman, NASA's deputy administrator, said during the news conference. "Further than we've ever been in over four decades, out into deep space and onward to Mars. These technology missions in deep space are really something to pause, reflect on — we're not just talking about it, we're doing it. And it's starting right here."

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.