Zap! Researchers Probe Origin of Mysterious Radio Bursts

Scientists took one step closer to solving one of astronomy’s mysteries when a team of researchers found convincing evidence of the origin of baffling, brilliant bursts of radio waves in the sky.

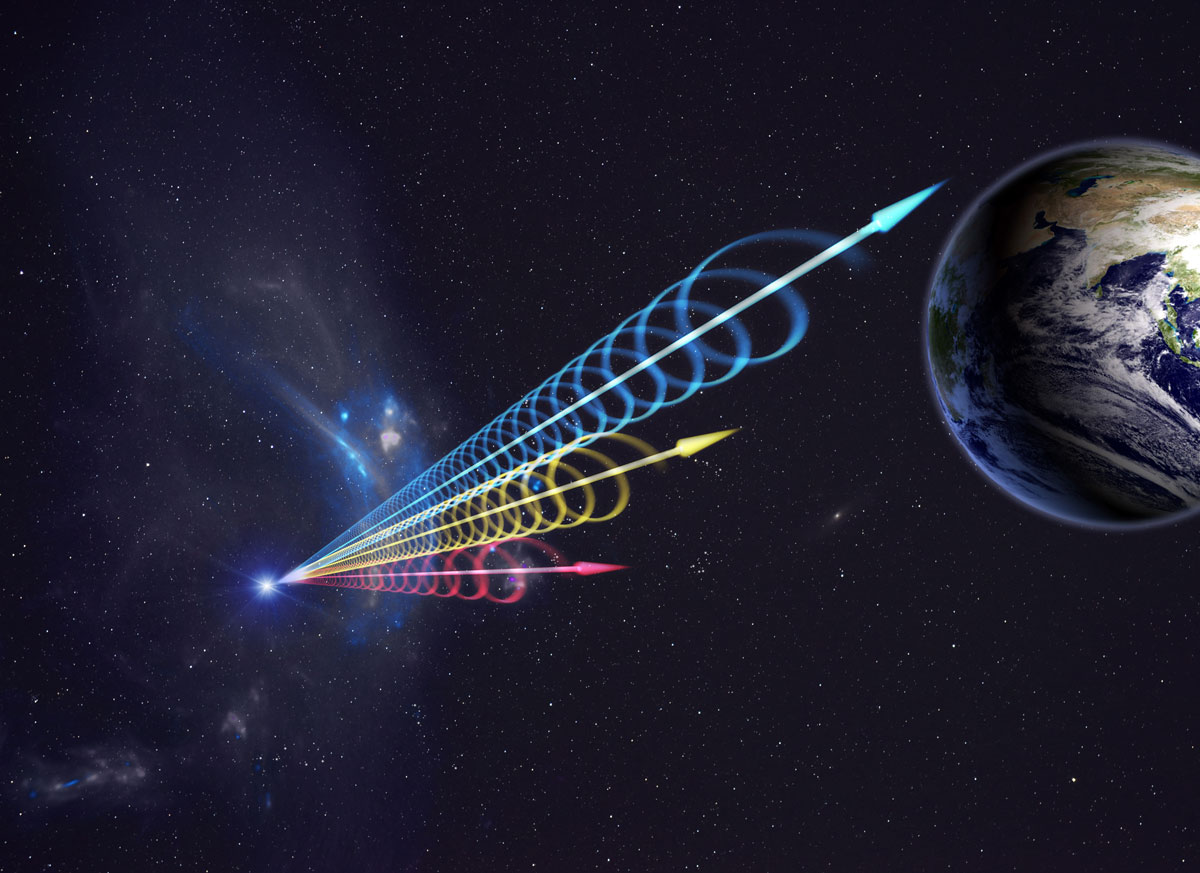

These fast radio bursts, called FRBs, are short eruptions of cosmic radio waves that last only a fraction of a second, yet pack a phenomenal amount of energy. Astronomers had only detected a handful of these events since they were first discovered nearly a decade ago, and their origin remained unknown. Now, a team of astronomers has compiled the most detailed record ever of an FRB by combing through 650 hours of data from the National Science Foundation's Green Bank Telescope. A new video describes the mysterious bursts and where the data suggests they might come from.

Their research shows that the newly identified FRB, dubbed FRB 110523, was born inside a highly magnetized region of space. [8 Baffling Astronomy Mysteries Today]

"This significantly narrows down the source's environment and type of event that triggered the burst," Kiyoshi Masui, an astronomer with the University of British Columbia and the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, said in a statement.

In fact, the FRB's source environment has been narrowed down to such an extent that the astronomers believe that it could have originated in only one of a few environments, such as a recent supernova or the interior of an active, star-forming nebula.

Using highly specialized software developed by Masui and his colleague Jonathan Sievers from the University of KwaZulu-Natal in Durban, South Africa, the researchers were able to first filter the data to find FRB 110523 and later break down information from that one event to determine its origin.

The software counteracts the effects of dispersion, the "smearing" of a radio signal as it travels through space. Dispersion would usually mask the presence of an FRB within radio data collected by the Green Bank Telescope. By counteracting its effects, Masui and his team found more than 6,000 possible FRBs and individually inspected each one before choosing to study FRB 110523, which their data shows might have originated from as far away as 6 billion light-years.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Part of the reason they chose that particular FRB was because its signal contained more details about its polarization, an important property of light, than any previously identified FRB.

"Hidden within an incredibly massive data set, we found a very peculiar signal, one that matched all the known characteristics of a Fast Radio Burst, but with a tantalizing extra polarization element that we simply have never seen before," Jeffrey Peterson, an astrophysicist at Carnegie Mellon's McWilliams Center for Cosmology, wrote in the statement.

The types of polarization the radio waves exhibited suggested that the FRB must have passed through a powerful magnetic field.

The researchers' dispersion-delay software was also able to narrow down the size of the source region, showing that the FRB came from another galaxy. Further analysis of the FRB signal shows that it also passed through two regions of ionized gas.

Only two things could leave such an imprint on the signal, the researchers noted in the statement: a nebula surrounding the source or the environment near the center of a galaxy.

"Taken together, these remarkable data reveal more about an FRB than we have ever seen before and give us important constraints on these mysterious events," Masui said. "We also have an exciting new tool to search through otherwise overwhelming archival data to uncover more examples and get closer to truly understanding their nature."

Although they have solid evidence of only a few FRBs, scientists believe these events blast into the observable universe thousands of times a day, National Radio Astronomy Observatory officials said in the statement.

Follow Kasandra Brabaw on Twitter @KassieBrabaw .Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Kasandra Brabaw is a freelance science writer who covers space, health, and psychology. She's been writing for Space.com since 2014, covering NASA events, sci-fi entertainment, and space news. In addition to Space.com, Kasandra has written for Prevention, Women's Health, SELF, and other health publications. She has also worked with academics to edit books written for popular audiences.