Meet Tayna, the Faintest Ancient Galaxy Ever Found

A newly discovered early galaxy is the faintest ever found, and it's giving researchers a rare look into how ancient galaxies evolved.

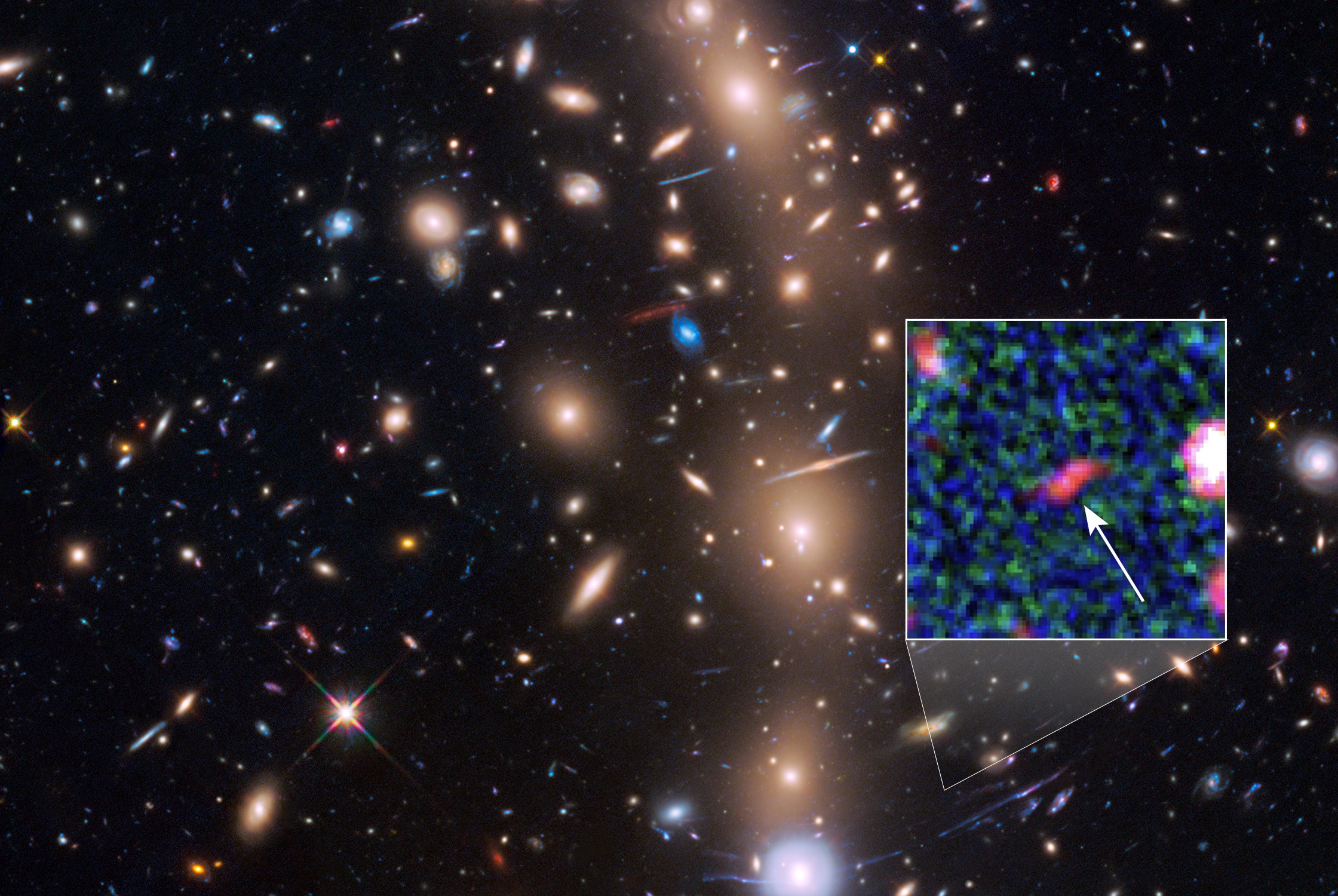

To peer into the distant universe is also to peer back in time. Researchers are seeing the tiny galaxy, which they nicknamed Tayna, as it existed 13.8 billion years ago. and the Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes were able to image it in the earliest stages of its evolution. The early universe was likely populated by many such newborn galaxies, NASA officials said, but few have been observed before now because of their extreme faintness.

The researchers detected the galaxy along with 21 other young galaxies near the outer edge of the observable universe. [Hubble in Pictures: Astronomers' Top Picks (Photos)]

"Thanks to this detection, the team has been able to study for the first time the properties of extremely faint objects formed not long after the Big Bang," lead author Leopoldo Infante, an astronomer at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, said in a statement.

The team called ancient newborn galaxy Tayna, which means "first-born" in the South American language Aymara spoken near Chile — it dates back to just 400 million years after the Big Bang. The galaxy is about the size of the Large Magellanic Cloud, a prominent star-forming dwarf galaxy orbiting the Milky Way, but it is forming new stars about 10 times faster.

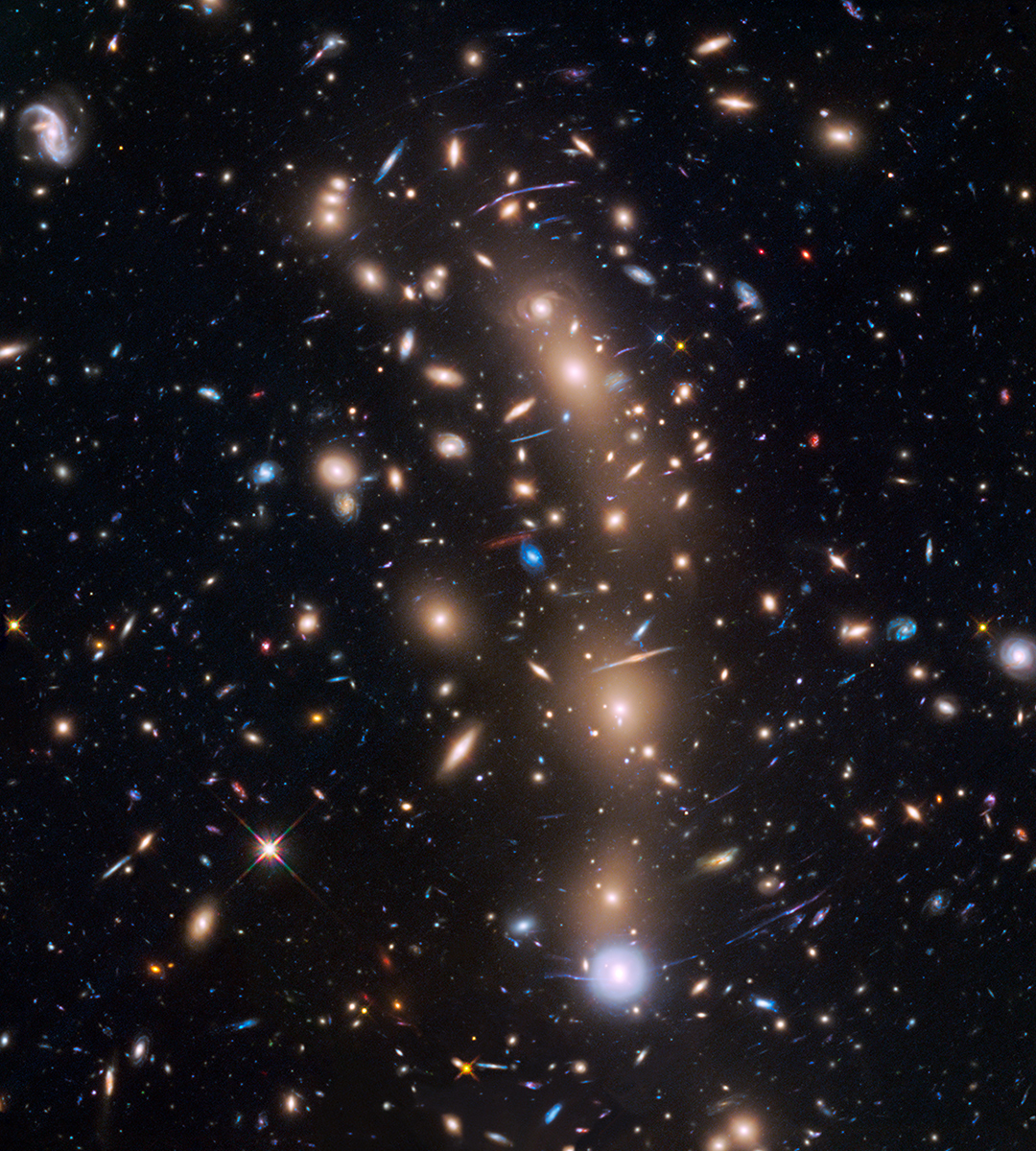

The super-faint galaxy was visible to the scientists' telescopes because of its lucky location: behind a massive galaxy cluster Hubble was investigating, whose bulk bent the far-away galaxy's light as it passed by. That bending acted like a magnifying glass, concentrating the galaxy's light to appear 20 times brighter than it would have otherwise.

To verify the galaxy's distance and age — it is likely the faintest ever found from that early in the universe's existence, the researchers said — the researchers combined Hubble and Spitzer images to determine its exact color on the infrared spectrum. Galaxies seen from the early days of the universe appear much redder, because of the speed they're moving away from us. Although Tayna's light was originally blue or white, its vast age means that it's moving away quickly enough to take on an infrared hue.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Astronomers caught this galaxy with the help of a naturally formed lens, but more powerful human-made lenses could reveal galaxies of a similar age without the lucky positioning. The new James Webb Space Telescope now under construction, for instance, will probably reveal many more of these faint galaxies near the dawn of the universe, NASA officials said in the statement.

The new research was detailed Dec. 3 in The Astrophysical Journal.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.