If Aliens Exist, Would They Have Sex?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Humans love to ponder whether alien life is out there, and what it might look like. So here's a burning question: Would extraterrestrials have sex?

The question isn't entirely prurient. The evolution of sex is a tricky subject. Sexual reproduction is costly. It requires finding a mate, convincing that mate to mingle DNA with you, and opening yourself up to the possibility of sexually transmitted disease or predation while you're busy wooing.

All that considered, and it might not even result in viable offspring. After all, mixing and matching a genome is a crapshoot, said Sally Otto, director of the Biodiversity Research Centre at the University of British Columbia. [7 Huge Misconceptions About Aliens]

Potential parents "know their genome works in the current environment," Otto told Live Science. "They know they survived to reproduce. And here they are, shuffling their genomes together with another individual. … You have no idea if that combination is going to survive and be fit."

And yet, sexual reproduction is very common on Earth. And given the conditions in which sex evolved, it's quite possible that aliens might get busy, too.

Swapping genes

Not all life on Earth requires sex for reproduction. Amoebas, yeast and millimeter-long freshwater hydra all manage to create offspring solo, as do many invertebrates. So do some surprisingly complex animals: Virgin births have been reported in Komodo dragons, pit vipers and sharks.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

There are species, like the tiny crustacean Daphnia middendorffiana, that can only reproduce asexually. But sex appears to go way back. There are few very old lineages that are entirely asexual, Otto said. [Photos: Bizarre Sex Lives of Hermaphrodite Sea Slugs]

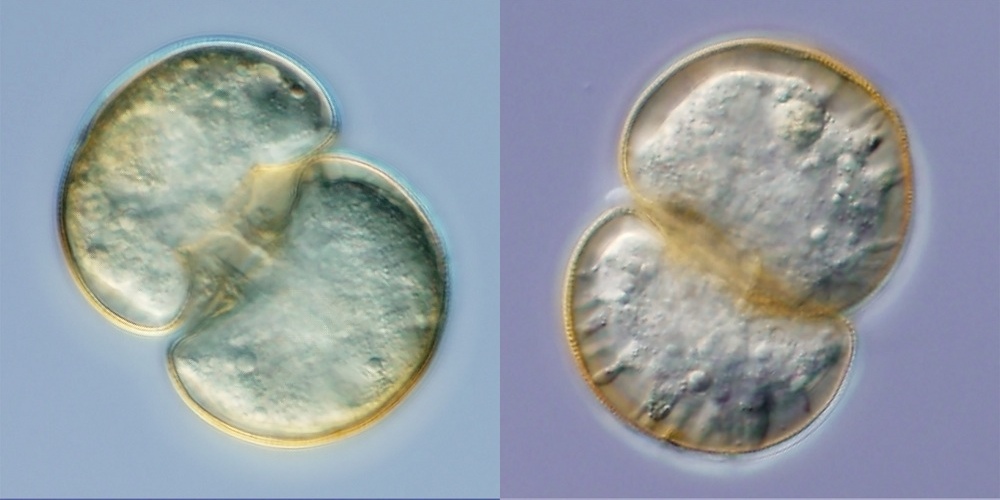

Amoebas, for example, date back at least a billion years, long before multicellular life evolved. For a long time, scientists thought amoebas were purely asexual. In 2011, however, researchers from the University of Massachusetts announced that they had discovered amoeba sex.

In fact, swapping genes is the norm for life on Earth. Bacteria, for example, are prokaryotes, meaning they don't have membrane-enclosed nuclei. (Eukaryotes, including both amoebas and animals, have cells with nuclei and other organelles closed in with membranes.) Bacteria don't have sex, Otto said, but they do take up new DNA by swallowing other bacteria or as a result of being infected with viruses or circular DNA molecules called plasmids. The inadvertent genetic gains can benefit bacteria by increasing genetic diversity, thus raising the chances that a new genetic sequence will confer some sort of survival benefit.

Sexual evolution

It's possible, Otto said, that deliberate sexual reproduction arose with the evolution of eukaryotic cells because all those internal membranes prevented the frequent accidental uptake of foreign DNA.

So, one question that might determine whether aliens have sex, Otto said, is what their cells look like.

"Do they evolve nuclei or other ways of protecting their DNA inside a series of membranes?" she said. If extraterrestrial life is equipped with nuclei, they might benefit from sex.

Another thing that Planet Xenon might need to prompt the evolution of sex is change.

Sex is very beneficial to organisms because the environment is rarely static, Otto explained. Offspring may have to deal with challenges that are slightly different from those of their parents' generation. As long as change is a constant, genetic variation is helpful.

If an alien planet had, for some reason, constant weather, temperature and other environmental factors, "sex would have mainly costs, but no benefits," Otto said.

Best of both worlds

Assuming alien planets aren't entirely static, extraterrestrials might try to get the best of both worlds. Some aphids (small insects that suck plant juice) clone themselves asexually when food is abundant. In fact, Otto said, these cloning aphids can have not only their babies inside them but also their babies' babies, "like a set of Russian nesting dolls."

"That really speeds up reproduction when resources are plenty," she said.

At the end of the growing season, though, the aphids switch to sexual reproduction. This switch to sex during times of stress is a common pattern. Some water flea species spring for sex when food supplies drop or when the environment becomes hostile, according to a 1981 study in the journal The American Naturalist. Yeast simply bud off new offspring most of the time, but the yeast Candida tropicalis can also reproduce sexually, researchers reported in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2011.

One stress that might prompt the evolution of sex on an alien planet might be alien parasites. Researchers reporting in 2011 in the journal Science found that, when given the choice, organisms pick sex over asexuality when parasites threaten, likely because sexual reproduction gives them more genetic weapons to use in the evolutionary arms race against their parasite foes.

In that study, researchers genetically modified roundworms called Caenorhabditis elegans so that some could only reproduce sexually and some only asexually. A third group was left to switch between asexual and sexual reproduction at will.

Then, the researchers exposed the worms to parasitic bacteria. They found that asexual C. elegans exposed to evolving bacteria went extinct in fewer than 20 generations. Sexual C. elegans did just fine, as did worms that could switch back and forth.

Other studies have shown similar results in yeast and other organisms that can switch from no sex to sex in tough conditions.

Hot stuff?

But even if aliens do have sex, it might not be the sort of thing people watch on pay-per-view.

In amoeba sex, for example, the cell partitions off packets of genetic material and then recombines them, either with another amoeba or with packets from other amoebas. Sexually reproducing yeast cells find each other, grow projections, merge and mate. The hermaphroditic C. elegansworm wiggles its body against another worm until it finds the vulva and then inserts needlelike structures called spicules into the opening to deliver sperm, according to WormBook, an open-access resource on C. elegans biology. [Animal Sex: 7 Tales of Naughty Acts in the Wild]

Even for fuzzier, more familiar animals, sex can get downright weird. The marsupial Antechinus, which lives in Australia and New Guinea, mates in a frenzy over about two weeks. Males often ambush females and copulate with them for up to 14 hours. The effort of their multiple marathon sex sessions takes such a toll on males that they start to bleed internally and lose all immune function. They rarely survive the breeding season. Hyena males have to mount females with care because the female clitoris is so large that it resembles a penis. And some male bats even stimulate females' genitalia with their tongues.

In other words, aliens might have sex, or they might not. But one thing's for sure: It'd be harder to invent something stranger than what already exists here on Earth.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on Live Science's Life's Little Mysteries.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Space.com sister site Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.